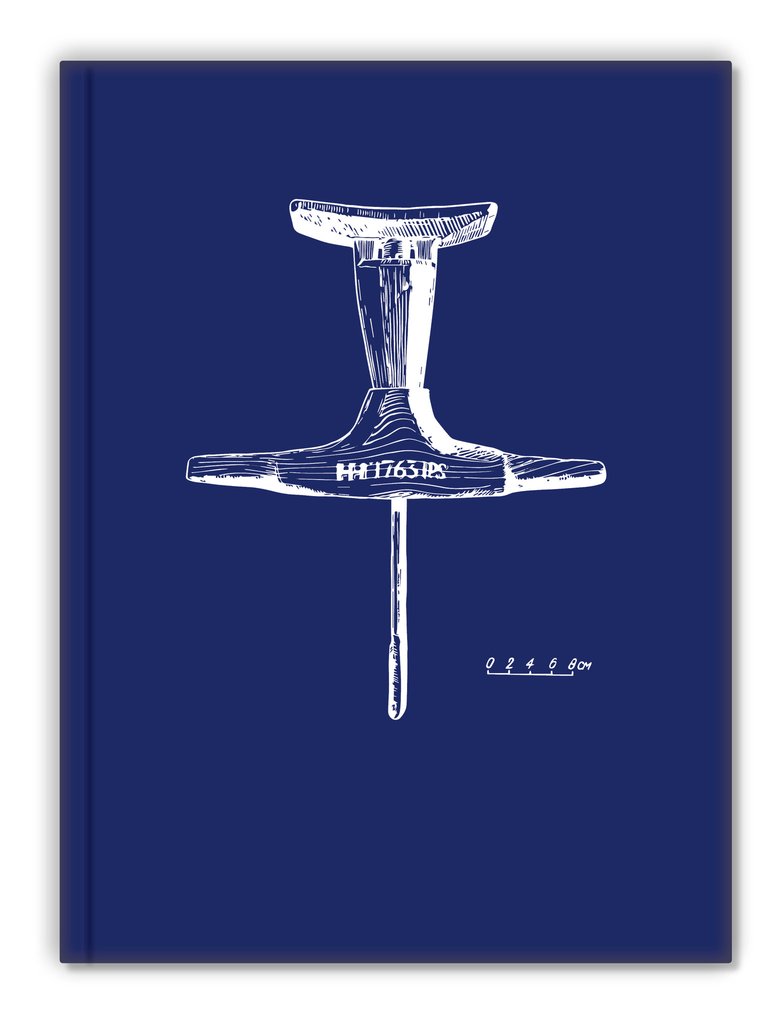

Publisher’s note: I don’t think I’ve ever dealt with publishing a book that has a more tortured history that “Woodworking in Estonia.” First published during the Cold War, the book was translated to English in 1969 under unusual circumstances, and the author never receive a kopeck for his efforts. Our edition seeks to reconcile that disgrace. Ants Viires’ family will receive royalties from every book sold. The book is available for pre-order in our store here. The book should ship in August. Here is the second part of how the first translation was completed. The first part is here.

Translations for Food

Keeping up with the number of publications that were available to U.S.-based scientists and the time it took for full translations was becoming problematic. There were at least 28 academies of sciences and several thousand research institutes in the USSR. Russian-language translations had been given priority, but by 1959 the number of non-Russian abstracts and translations had to be expanded. More translations and the money to pay for them were needed. Enter the American Foreign Food Assistance Program and Public Law 480.

Public Law 480 (PL 480), otherwise known as the “Food for Freedom” program, was signed into law in 1954. The agricultural bounty of the United States was a foreign policy tool that was initially used to help countries recover after the war and keep domestic prices from falling. It was also a means of discouraging communism. Under PL 480, agricultural commodities could be sold to foreign governments for local currencies, donated for famine or emergency relief abroad, or used for emergency situations in the United States. After a country’s request for aid was approved, the U.S. firms providing agricultural goods were paid in U.S. dollars while the importing country paid for the aid in the local currency.

Currencies were paid to the U.S. Embassy in the receiving country. According to the United State Senate Committee on Agriculture and Forestry, under Title I of PL 480 foreign currencies accrued from the sale of agricultural commodities could be used among other things “for international educational exchange…for carrying out programs of U.S. government agencies…” Using the provisions of PL 480 the NSF could set up contracts for translation services in countries receiving U.S. agricultural goods and the services were paid for with the local currencies accruing at the U.S. Embassies. In 1959 the NSF signed its first translation contract with the Israel Program for Scientific Translations (IPST).

IPST was formed by the Israeli government and employed multi-lingual scientists to translate books and other Soviet-bloc publications in chemistry, physics, medicine, biology, mathematics and other fields. Many of the scientists received their education partly in the Soviet Union and partly in English-speaking countries. The 150 or so translators were scientists from the faculties of Hebrew University, the Israeli Institute of Technology and research staff of other institutes. By 1964 IPST had translated 330 books and 800 articles totaling 110,000 pages. The translated publications were printed in Jerusalem and available in the United States through the Office of Technical Services of the U.S. Department of Commerce. Complimentary copies of the English editions were sent to the origin countries in the Soviet Union, and IPST also sold editions to 60 other countries. In 1960 similar translation contracts were signed with groups in Poland and Yugoslavia.

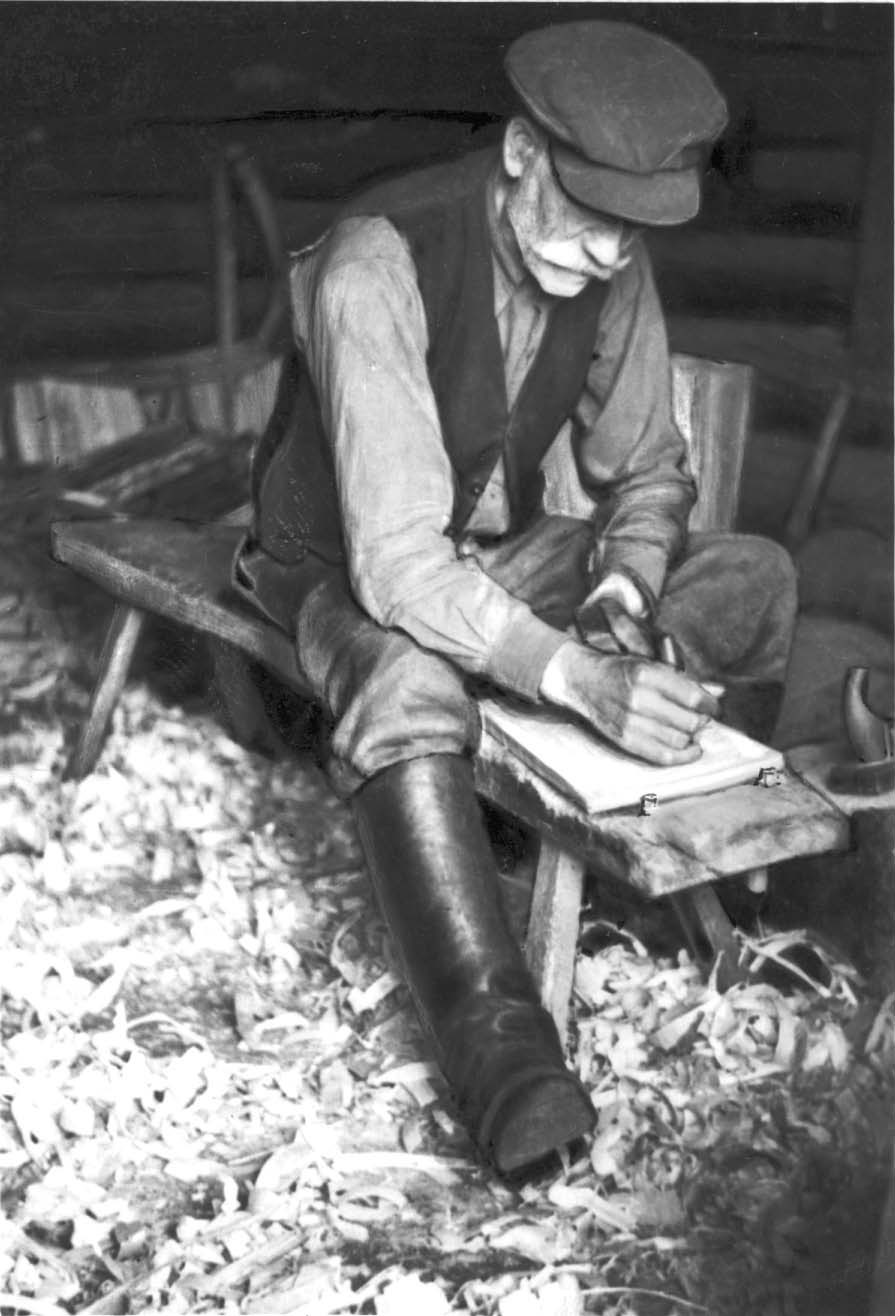

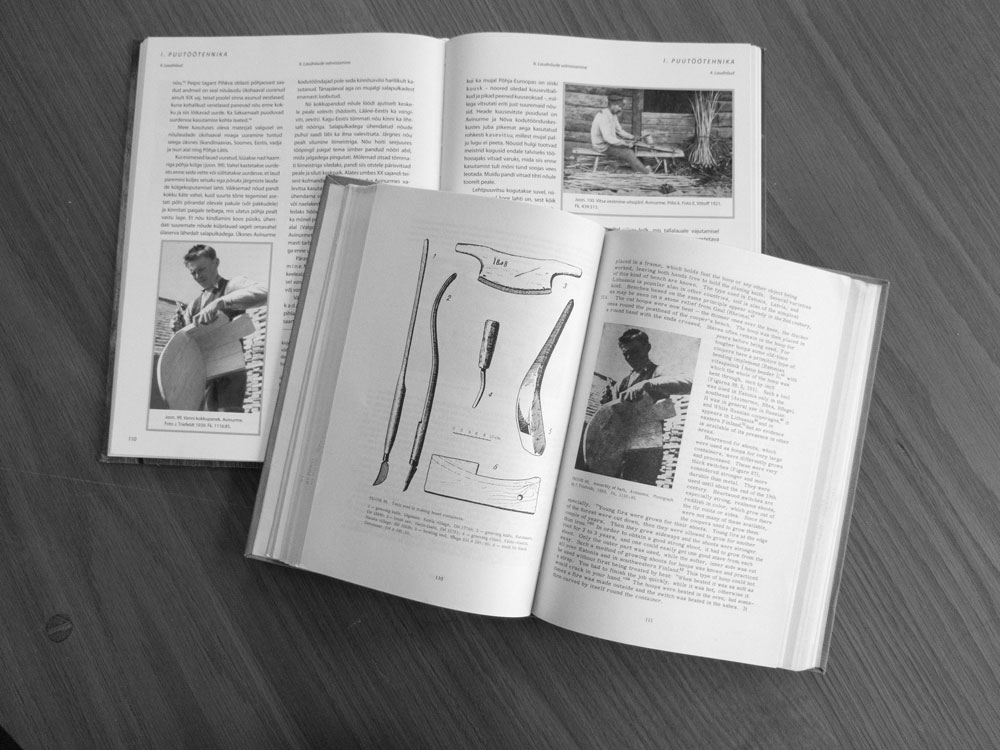

In 1960, Viires’ doctoral thesis “Eesti rahvapärane puutööndus: ajalooline ülevaade” was published by the Estonian Academy of Sciences. The full publication of a thesis was exceptional in the Soviet Union. Abstracts and articles summarizing the thesis were required by the author and printed in limited numbers but were rarely available abroad. It seems despite his “undesirable background,” Viires’ work was deemed too important not to be published in full. However, for this type of publication no royalties were paid. In the April 1961 edition of the “East European Accessions List” of the Library of Congress, Viires’ monograph was listed for the first time.

Through listings in several U.S. government publications, a request for a cover-to-cover translation, the translation of select journal articles, or an abstract could be made. The NSF coordinated the requests with various agencies including the Atomic Energy Commission, the National Library of Medicine, NASA, the Smithsonian Institution and the Departments of Agriculture, Commerce and the Interior. Lists of available translated material (with prices) was published regularly. Copies of translated publications were also deposited at the Library of Congress and several major university libraries.

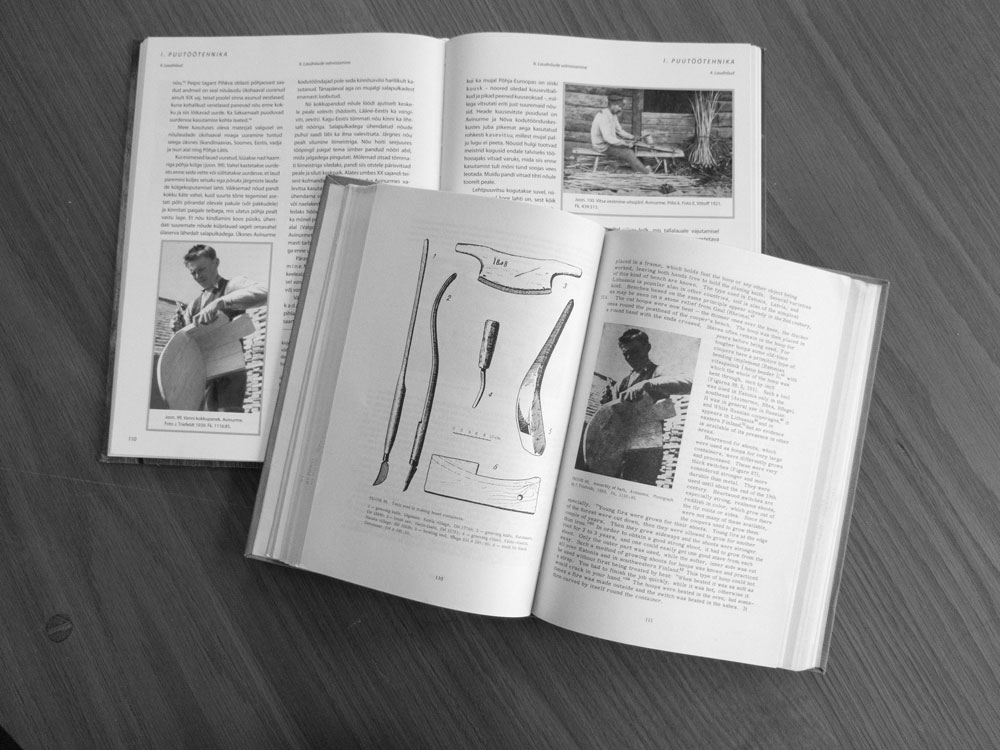

In the case of “Woodworking in Estonia,” the Smithsonian requested the translation from Estonian to English. Translations by the IPST followed a four-part process with reviews by the editorial staff, science-area specialists and English-language stylists who were immigrants from the United States, South Africa and Britain. The first listing showing the translation was underway was in the CIA’s “Consolidated Translation Survey” of January 1968. It was listed under USSR-Economics as “Estonian Wood Carving Industry.” Once the translation was completed it was listed in the same CIA publication one year later under Scientific-Miscellaneous as “Woodworking in Estonia.” The U.S. Department of Commerce, responsible for sales and distribution, provided a full description of the newly translated book in the “U.S. Government Research & Development Reports” of April 1969.

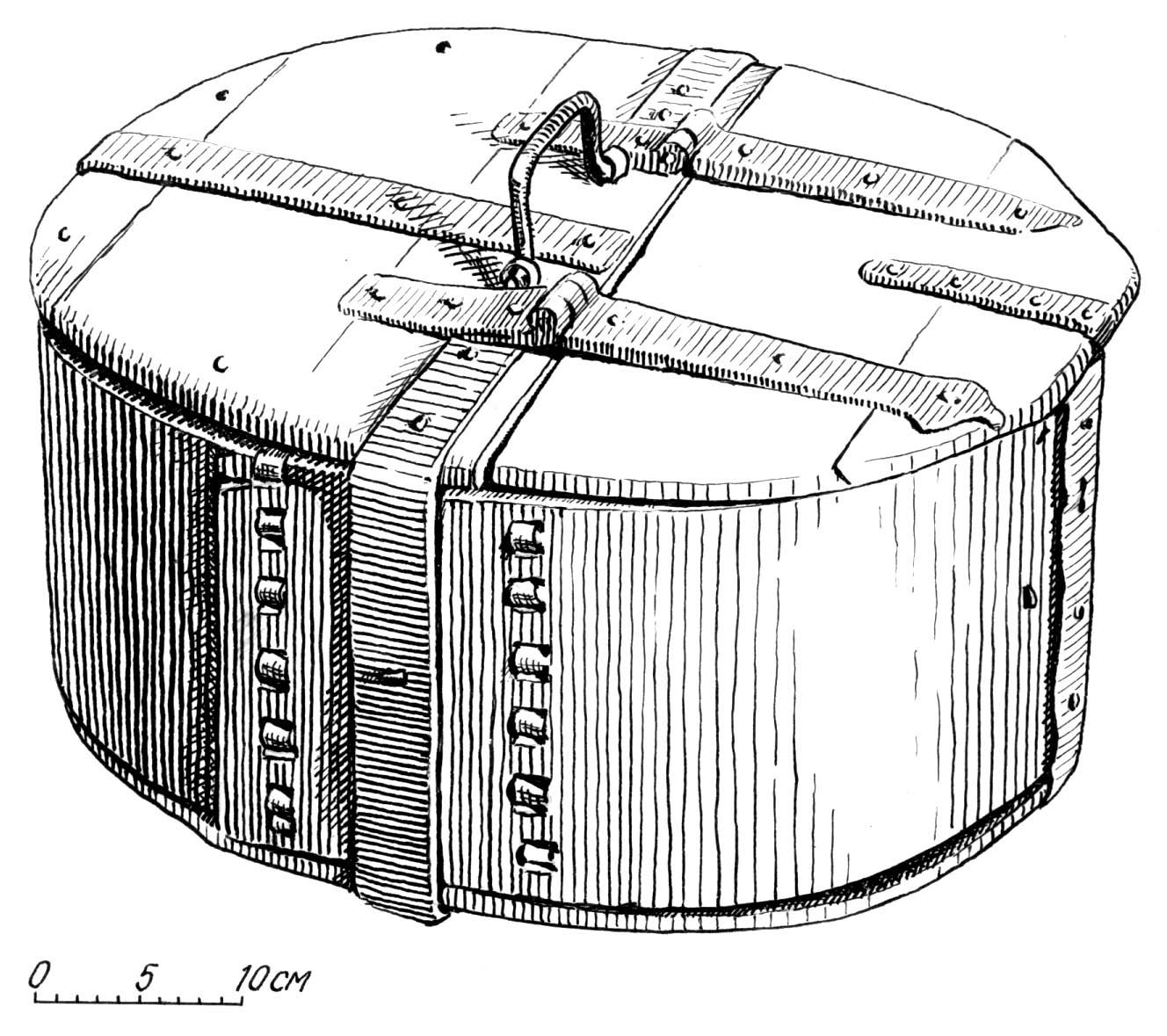

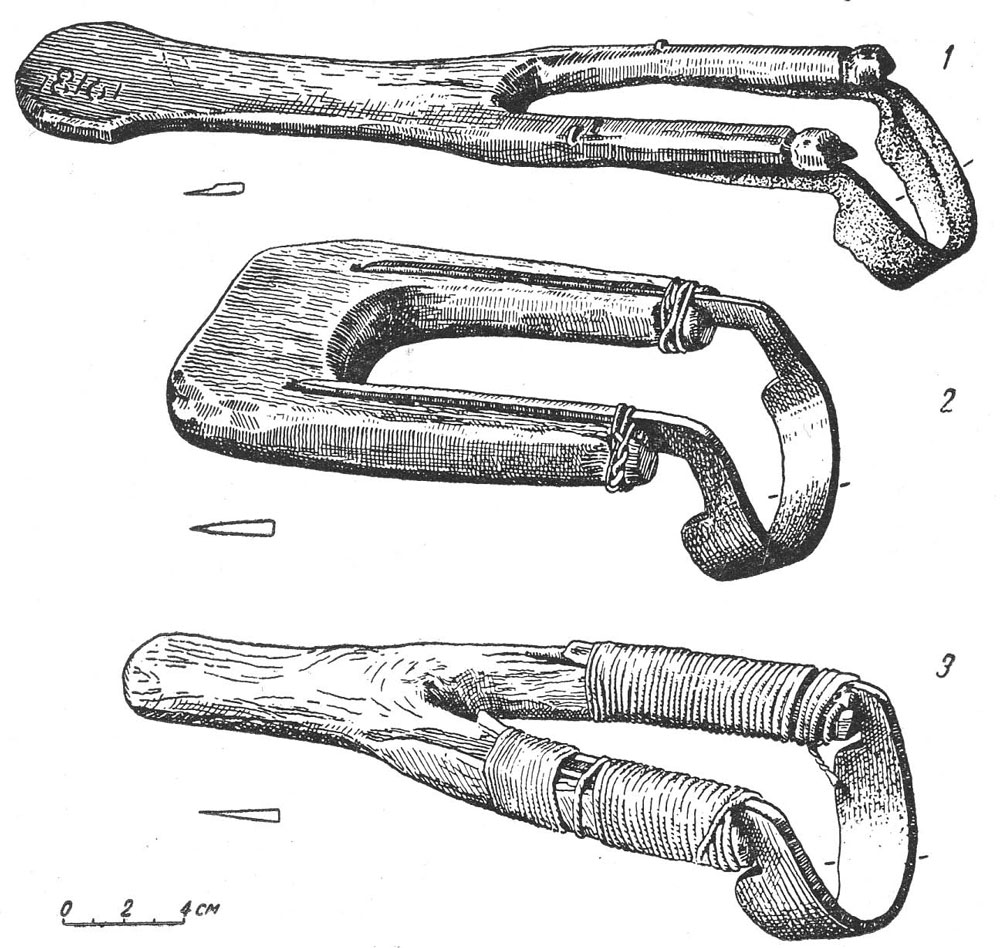

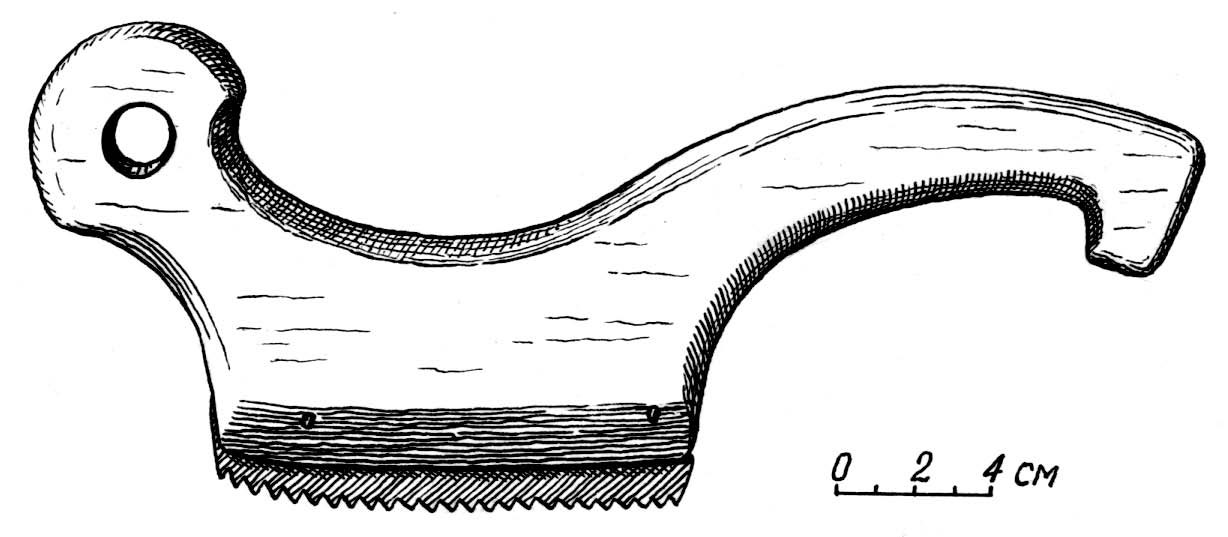

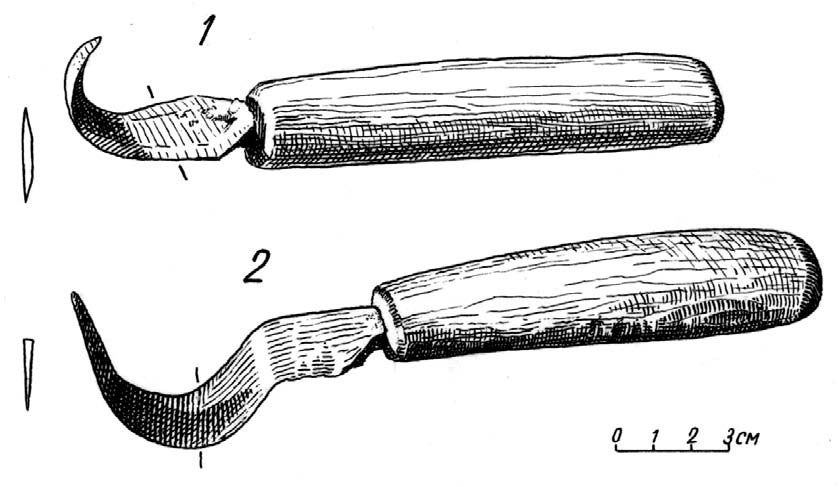

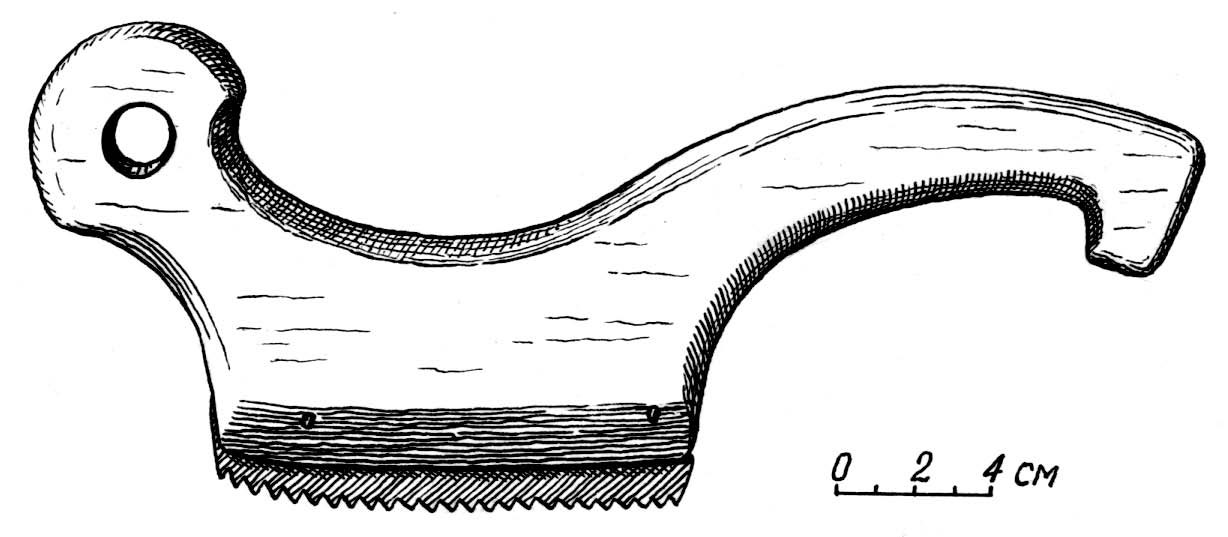

“Woodworking in Estonia: Historical Survey” was described as “Wood, material forming. Culture, USSR. Rural areas, Trees, Small tools, Containers, Bending, Joining, Anthropology, Economics.” Identifiers were: “Social anthropology, Estonia, Woodworking, Turning (Woodworking), Handicrafts, Furniture.” As was the usual practice for an author in a Soviet-controlled country, Viires did not know his Estonian-language monograph had been listed in a U.S. government publication, selected for translation into English, translated by the IPST and made available for sale in the United States. He received four copies of his translated work, but no royalties.

Late in Estonia’s pre-1940 independence period, copyright laws based on the German model had been drafted but were not enacted prior to the Soviet occupation. During the occupation Estonia was subject to the copyright regulations in the Soviet Civil Codes. The Soviet Union was not a member of any international copyright convention until 1973. Prior to this, a work was copyrighted from the moment of creation, not publication, registration was automatic and royalties were determined by state-regulated schedules. In the spirit of “the work of one should be for the benefit of all,” creative output was essentially owned by the state. Large portions of a published work could be used without the author’s consent and using the work of another was not considered a theft of intellectual property. The first Soviet copyright laws were in place in 1925, with changes in 1928 and 1961, and each Soviet republic was required to be in compliance. Adding to the lack of an author’s rights was the provision for “freedom to translate.” This was a holdover from Tsarist laws that allowed a work in Russian to be translated and published in the minority languages of the country without the original author’s consent. The state could forcibly nationalize any work and also held a monopoly over the printing and publishing industries. The “freedom to translate” provision was not abolished until the Soviet Union joined the Geneva version of the Universal Copyright Convention (UCC) in May 1973. Joining the Geneva version was chosen to avoid the implementation of the Paris accords of the UCC, which gave authors stronger rights over their work.

By 1969 Viires had been studying Estonian language and culture for 32 years. For 29 of those years the Soviets, the Nazis and again the Soviets were determined to wipe out Estonian identity, language and culture while Viires, working in the constricts of an occupied country, was just as determined to document and preserve those same things. According to his family members, Viires was surprised but pleased his work was translated into English and he added the translation to his bibliography. As Liina Viires, Ants’ daughter, explained, to have one’s work translated and published abroad was a good thing. Under the Soviets travel abroad and receiving foreign guests was severely limited and even large areas of Estonia were off-limits. Even though authors in the Soviet era had little control over their work, the opportunity to have one’s work published abroad was a validation and it might open up the possibility, however slight, to communication with one’s peers in other countries.

The publication of Ants Viires’ doctoral thesis was exceptional in the Soviet system. In the 1960s someone at the Smithsonian saw in Viires’ monograph the potential for a valuable addition to the history of woodworking and folk handicraft, and requested a full translation. Although the translation was done without the knowledge or permission of the author, it brought this unique record to the attention of American woodworkers and eventually led to the authorized English translation you are holding today.

— Suzanne Ellison

Like this:

Like Loading...

There are a million people involved in this project to thank, from the Viires family, to David Laaneorg (who first got us in touch with the family), to Mart Aru who translated the text, to Meghan B. who dove into the European-centric design, to Suzanne Ellison, who braved the index, to Peter Follansbee who gave us the first important edit, to Megan Fitzpatrick, who helped me root out every typo we could find.

There are a million people involved in this project to thank, from the Viires family, to David Laaneorg (who first got us in touch with the family), to Mart Aru who translated the text, to Meghan B. who dove into the European-centric design, to Suzanne Ellison, who braved the index, to Peter Follansbee who gave us the first important edit, to Megan Fitzpatrick, who helped me root out every typo we could find.

While I was playing with

While I was playing with