For better or worse, my chairs tend to flirt with stretchers. Should the chair have them or not?

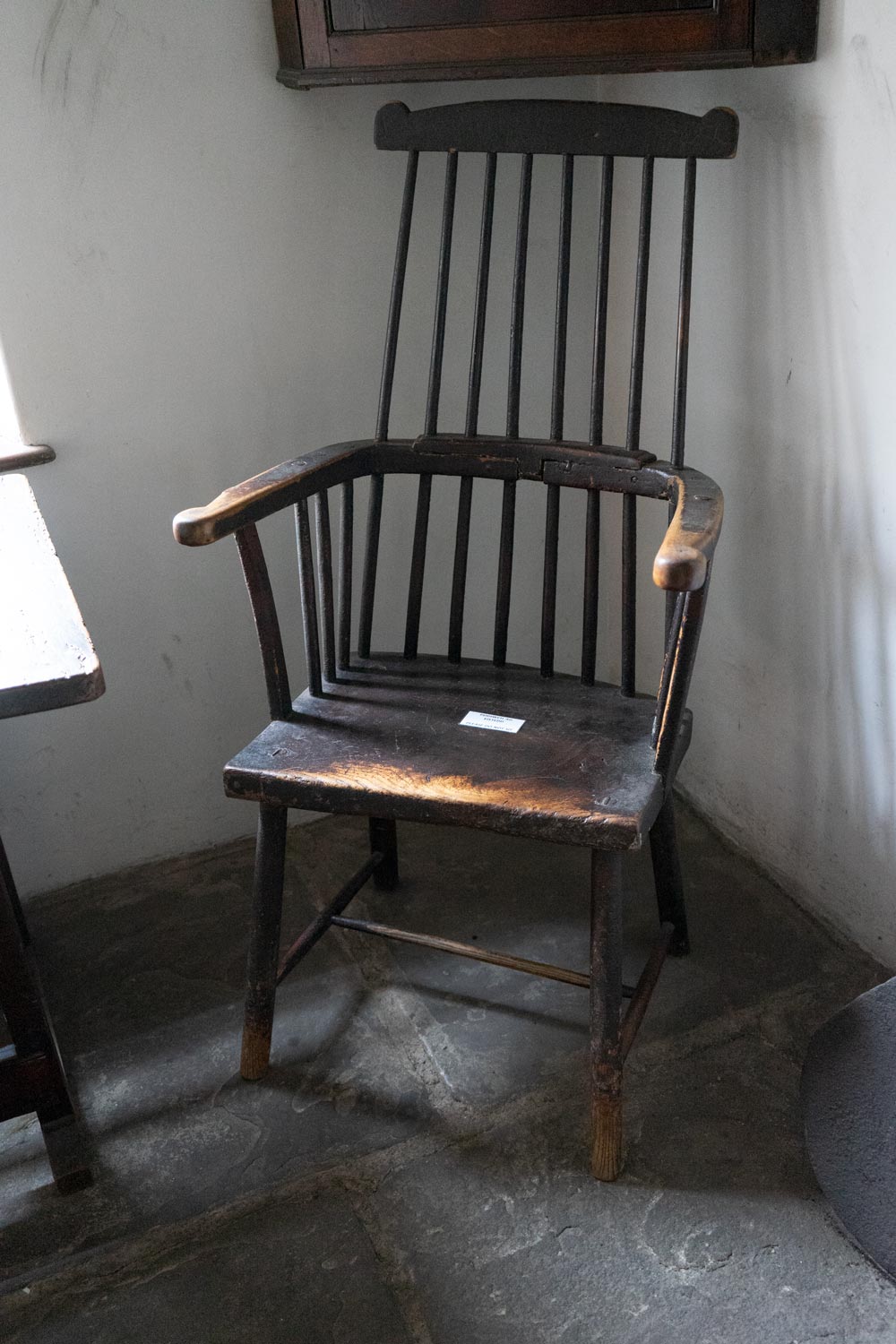

While common sense might dictate that all chairs should have stretchers between their legs for added strength, the historical record disagrees. Early chairs were just as likely to skip the stretchers.

Why? It’s anyone’s guess. Chairs with stretchers are almost certainly more durable. The legs are less likely to come loose when someone kicks them inadvertently or drunkenly. But chairs without stretchers are far easier to repair if a leg does become loose.

Chairs with stretchers are certainly more complex and require additional time to build. But they offer another opportunity for the maker to embellish the chair with turnings, balls and tapers.

Stretchers are a good place to put your feet. But they take a beating from feet and can look like dog crap in short order.

For me, however, stretchers can grant me a good night’s sleep.

This week I’m building a couple of Welsh stick chairs in some crazy curly white oak. This particular design, one I’ve developed through 15 years of flailing, doesn’t use stretchers and looks just fine to my eye. That is, until it doesn’t.

The front legs of this design use a 16° resultant angle to set the legs’ rake and splay. The back legs use a 22° resultant angle. While reaming the front legs I grabbed the wrong bevel gauge. As a result, the front legs are splayed out more than expected. And the legs rake forward more than expected.

When I finished the job, I knew it was wrong. But when I assembled the chairs and put them on the ground, I was happy with the additional rake and splay. It made the chair look rakish and splayish.

I sat on the chairs to see if they were solid. They felt fine, but I asked some friends to sit in the chairs and I watched the legs. They moved too much for my taste. I lost confidence in the chairs as-is.

So I started making stretchers for both of the chairs. This added two hours of work to the job, but it set my mind at ease. It made me wonder: Is this how stretchers were first invented? Perhaps an ancient chair without stretchers flexed just a little too much and the builder thought: I have to put some sticks in there to fix that.

Or not. Whatever.

— Christopher Schwarz