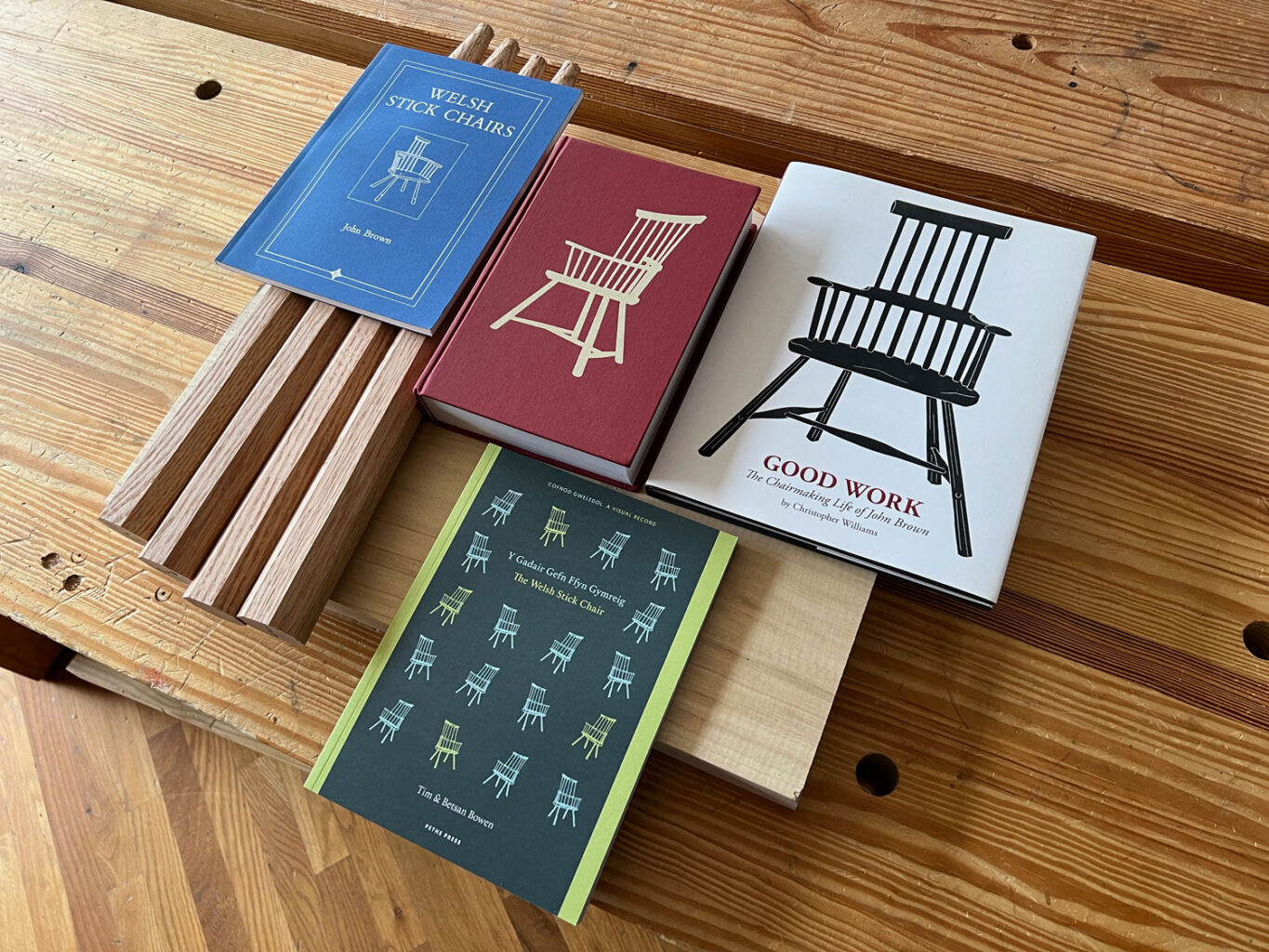

I never planned on trying to drag a bunch of readers into my Stick Chair Lair, but it sure looks that way in our store. We now have four titles devoted to these chairs, plus plans, a sliding bevel, a calculator for designing your own chairs, a bevel-setting tool and a card scraper specially ground for these chairs.

This wasn’t by design, I promise you. Heck we don’t have financial forecasts or a strategic long-range map for the editorial future of Lost Art Press. (Except this: We are going to bring back turned ashtrays.)

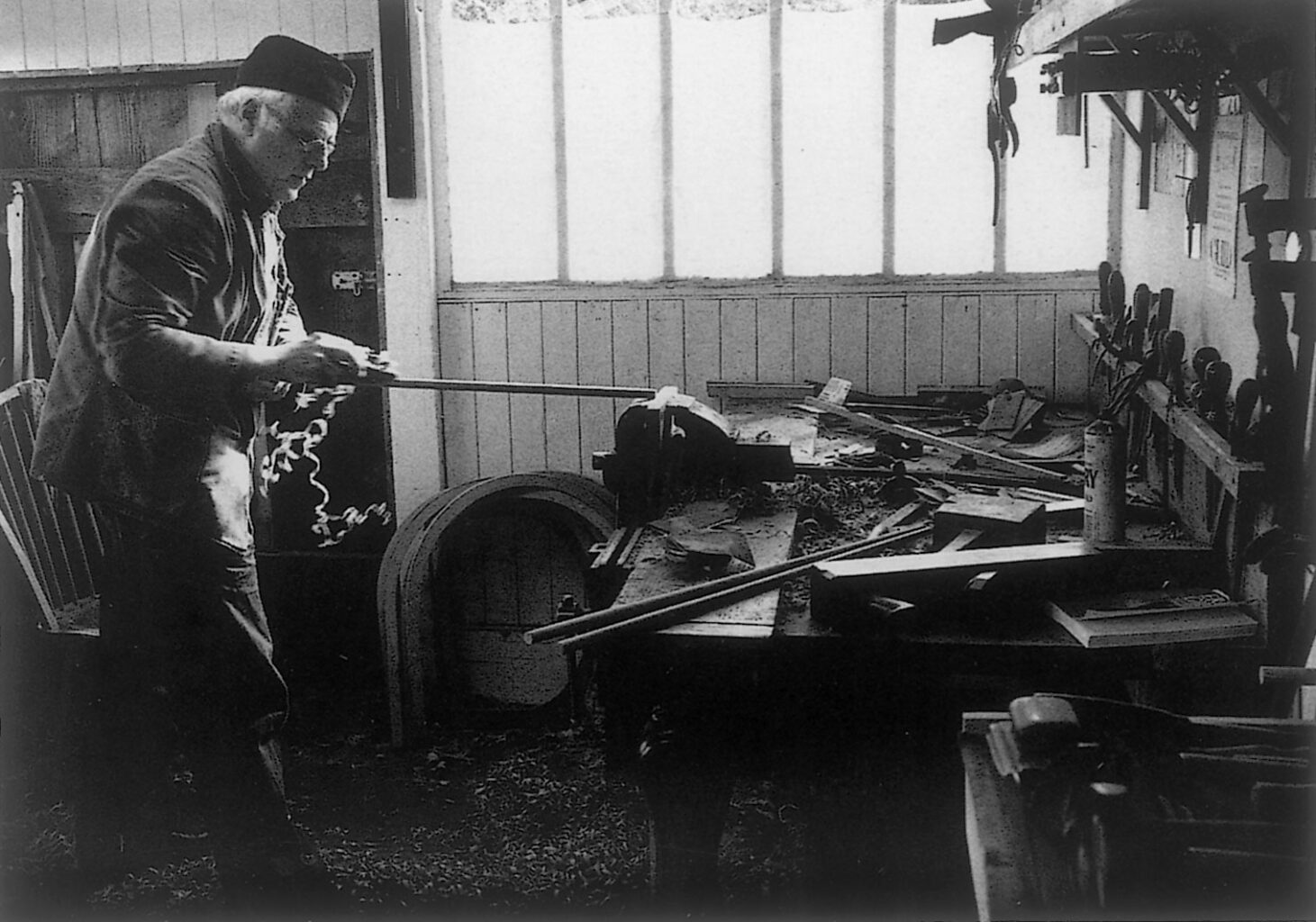

Stick chairs have been a long-running obsession of mine since 1997 or so when I first began reading John Brown’s column in Good Woodworking magazine. I started making these chairs in 2003, and I haven’t stopped since.

If you think these chairs are ugly (a common reaction – until you see enough of them), then here is a short explanation as to why I always seem to have one in progress on my workbench.

I love stick chairs because they are deeply rooted in traditional culture, and yet there are almost no hard rules about what they should look like or how they should be made.

In contrast, for years I built American Arts & Crafts furniture, which has a hierarchy of makers, techniques, finishes and forms. Yes, there are some outliers (Limbert, for one), but otherwise there are well-defined rules about what makes a “good” piece from a “blah” one. And those rules aren’t entirely about aesthetics.

With stick chairs, almost anything goes. Want to make a chair that has five legs, 11 sticks made from branches in your yard and a piece of carved driftwood for the comb? OK! And hey, you wouldn’t be the first person to do that. For me, these chairs represent almost complete design freedom – freedom to explore different materials, angles and dimensions, and even to create new forms (see the “Sticktionary” chapter in my book for a sample).

With this freedom comes responsibility. Though you can build whatever you like, your chair can also be ridiculed for poor proportions or its lack of a cohesive vision. And again, you wouldn’t be the first to make an awkward chair. A fair number of old stick chairs are butt-ugly. (Though many of the surviving chairs are beautiful.)

We all have a few ugly chairs inside of our hands, so it’s important to get those shambling thickets out through our fingers so we can develop chairs that offer grace, movement and comfort. The good news here is that stick chairs are insanely quick and easy to build compared to most other forms of chairs. So your journey won’t be long.

The joinery is made with drill bits for the most part (I use mostly cheap spade bits). You don’t need a lot of specialty tools to build them (mostly a jack plane and a block plane), and you can use whatever wood that’s on hand. Yes, kiln-dried wood from the lumberyard is fine – you just have to be a little picky about choosing straight grain.

And once you’ve made one chair, you’ll find the next one will come easier and faster. In the early days it took me a couple weeks to build a chair. Now it’s less than three days. Because they are so fast to build, I can explore lots of new forms and details. I have yet to build the same chair twice (though I have tried a couple times).

As a result, the work is never boring or repetitive, even after almost 19 years of building these teenage swans.

Oh, I almost forgot to mention the last little benefit of building these chairs. Making them will open up a huge world of staked furniture for you. The skills for making stick chairs directly translate to making staked tables, stools, workbenches or really anything with angled legs.

So how do you get started?

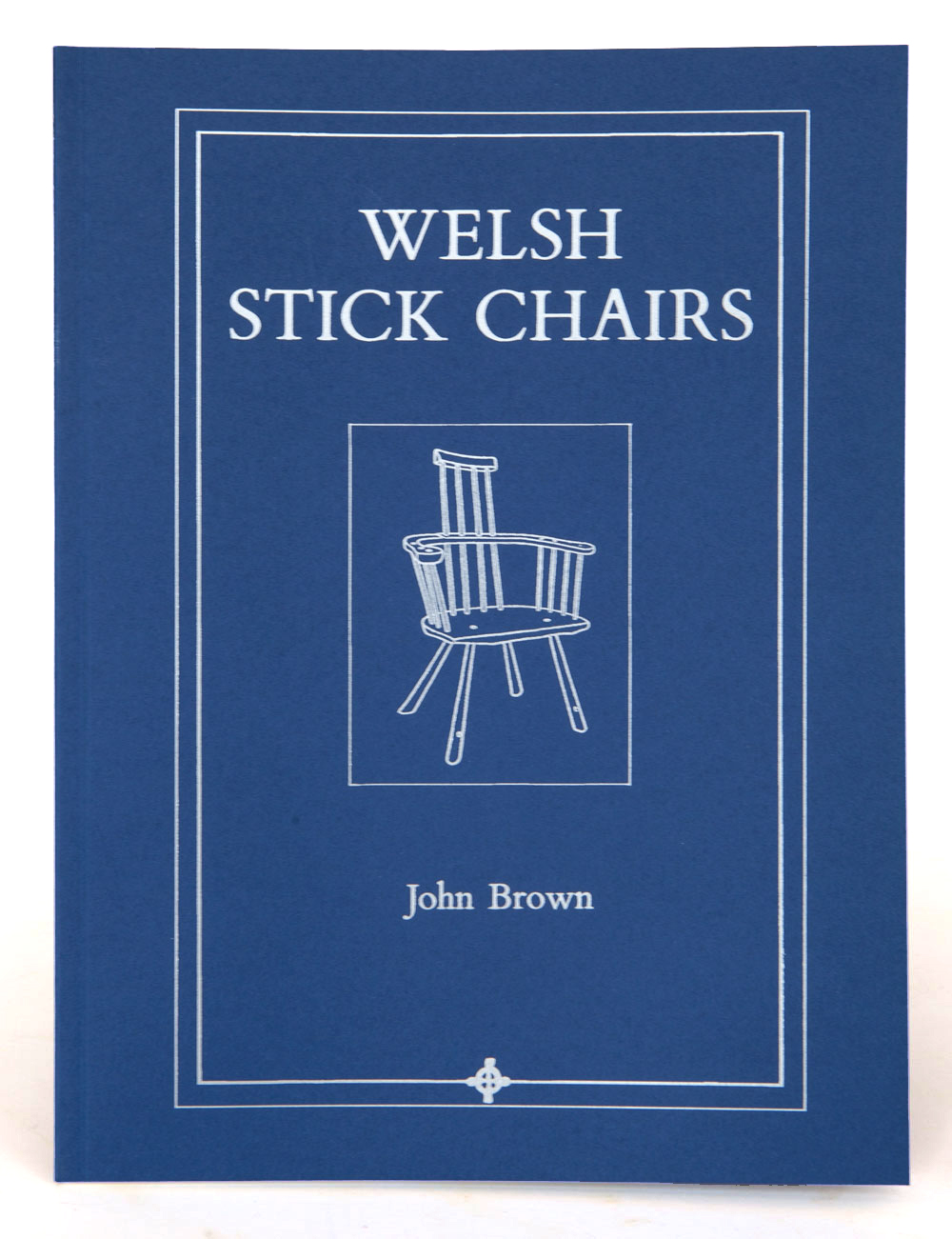

I’d begin with John Brown’s classic “Welsh Stick Chairs.” It’s a short book, filled with fire and brimstone, history and handwork. You can read it in one sitting. It will give you a taste for the different chair forms, those both funky and sublime. And you’ll get a full dose of John Brown’s cranky and iconoclastic way of working. His writing led me to the realization that I could build these chairs out of any damn wood that I pleased.

The second book I’d read is “The Welsh Stick Chair: A Visual Record” by Tim and Betsan Bowen. This is the only book we sell that we do not publish – that’s how important it is to me. This gorgeous book will show you what the stick chair form is capable of achieving in terms of beauty. The Bowens are highly knowledgeable dealers who have seen more of these chairs than anyone I know. The text is brief and fascinating. If you aren’t in love with these chairs by the end of this book, you probably shouldn’t delve any further.

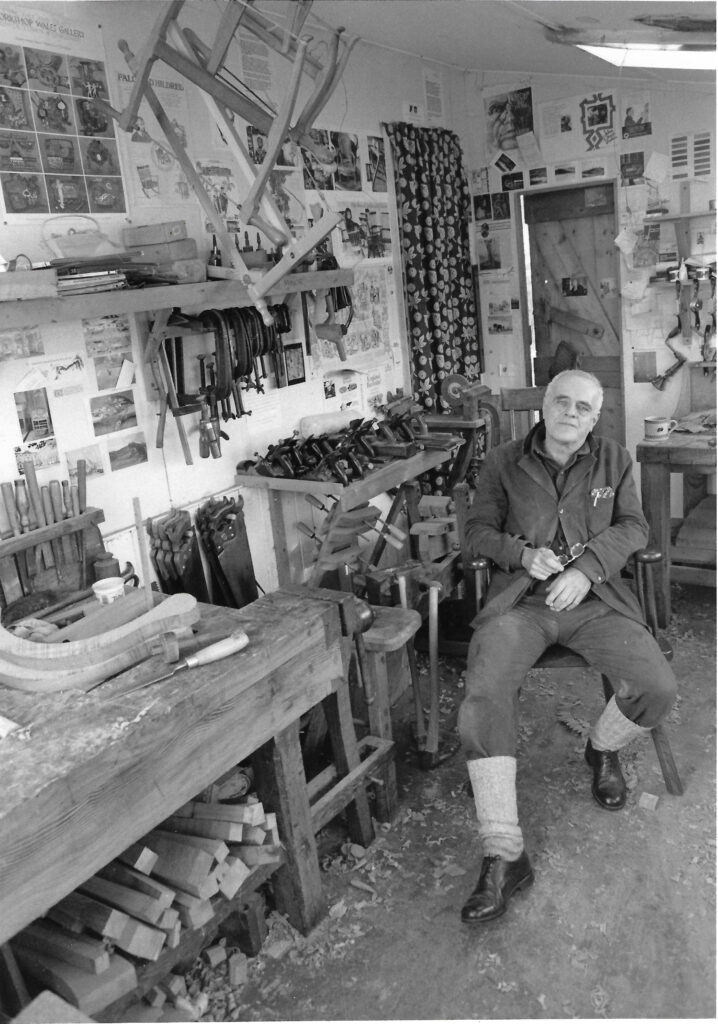

And the third book? Well that depends on how you like to learn. “Good Work: The Chairmaking Life of John Brown” by Christopher Williams is a deep dive into JB’s life as a chairmaker. It is one part biography – Chris worked with John Brown for about a decade building these chairs; he knows them inside and out. It is one part philosophy – the book contains John Brown’s best writing on chairmaking, none of which has been published in the U.S. And it is one part how-to. Chris demonstrates how John Brown built a stick chair, but he teaches it the way that Chris was taught. No plans. No exact dimensions or angles. Instead, each chair is a voyage of discovery, combining the wood on hand with a set of well-explained skills so you can build a chair of your own making.

If you are a woodworker who prefers explicit plans, then “The Stick Chair Book” might be a better choice. The book has complete plans for five stick chairs (two Irish, two Welsh and one Scottish). Plus detailed chapters on how to perform all the operations with a basic set of hand tools and a band saw. And chapters on finishing, wood selection, design and the like. Of all the books above, it’s most like a traditional woodworking text (with animal jokes).

After that, you are good to build a chair. Honestly. If I can build a stick chair, then dang-near anybody can build a good stick chair. Heck, you might even be able to build a great one.

— Christopher Schwarz

p.s. If you prefer looking at chairs to making them, we also offer a “Family Tree of Chairs” letterpress poster and a reprint of Edwin Skull’s circa-1865 broadsheet of the 141 chairs made by the Skull firm in High Wycombe, England.