Recently I was contacted by artist Tina Gagnon (www.tinagagnon.com) who, in undertaking some research, ran across the following profile of Henry O. Studley in a local newspaper. While some of the minor facts of the piece are at odds with other historical records, it is nonetheless an interesting peek into the life of this man.

— Don Williams, the author of “Virtuoso: The Tool Cabinet and Workbench of H.O. Studley” and the man behind donsbarn.com.

HAS LIVED 82 YEARS AND HAS LIVED THEM WELL

Henry O. Studley Tells Patriot-Ledger a Clear Conscience is His Secret of Long Life

“It must be a clean conscience” was the answer that H. O. Studley of 66 Washington street of this city gave when asked the secret of his long life.

Evidently he has found the fabled fountain of eternal youth, for when a stranger is told that the local man has lived 83 years, and apparently lived them well, there arises a genuine surprise in the mind of the of the questioner as to the accuracy of the statement, so misleading is his appearance.

It is suspected that this man, who is one of the oldest Masons in the city of Quincy, and a Grand Army member of the local post, is something of a philosopher and it is known that he is a genial gentleman with a sense of humor.

His moral guidance has been to a considerable extend the Golden Rule, and he believes that what is wicked to do on Sunday is wicked on any other day in the week; and while not a member of any church denomination he believes fully in another phase of existence after this life and has a strong suspicion that there may be, under suitable conditions, a communication between the two.

Work, plenty of work, carefully and beautifully contrived work of the hands, along the lines of wood carving and metal work, has occupied the time of Mr. Studley, both as a vocation and means of amusement in the years of the past.

Judging from the many artistically patterned specimens which he possesses, his hands have never been idle; but pretty things of beautiful woods, and these many times inlaid with mother-of-pearl and silver, have made many others happy as well as himself.

Not that all the happiness he has provided has been from beautifully wrought presents, for he has been a musician of repute, especially in playing the banjo, and audiences in various sections of New England have had the opportunity to enjoy his music.

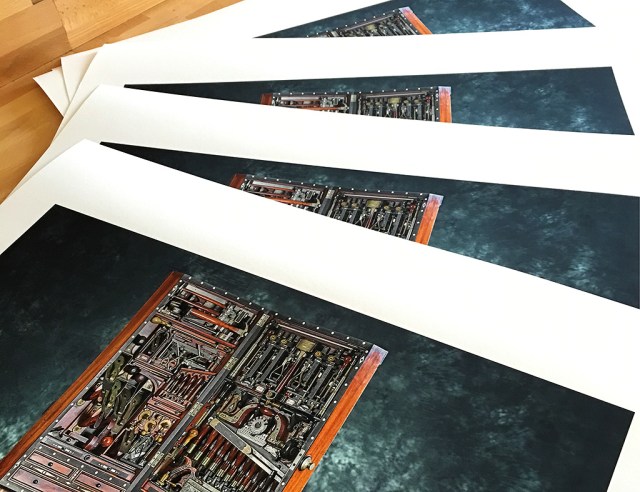

It was because of a very remarkable tool cabinet in his possession and his own work, together with the tools themselves, that the representative of the Patriot-Ledger chanced to meet Mr. Studley in his home here.

The cabinet is of a most ingenious contrivance, containing a multitudinous number of tools of all sizes and kinds, each of which may be removed without misplacing another through a peculiar layer system that has been instituted.

The cabinet was built when Mr. Studley was employed by the Poole Piano Company, a firm for which he worked for about 20 years, completing his duties about three years ago.

His firm was particularly proud of this cabinet and in a paper issued by the company was an article devoted to the maker, with a picture of Mr. Studley and his remarkable cabinet and tools. The article was considerably copied by other trades papers.

Under the caption, “Leading Craftsman Devoted Life to the Study of Instruments,” the following information was given:

The Poole Piano Company has in its employ an action finisher in the person of H.O. Studley, who ranks among the leaders of the trade’s best craftsmen. He has devoted a life to piano manufacturing in its various departments and prides himself on a tool cabinet of his own manufacture, which probably cannot be duplicated in the trade.

“A place for everything and everything in its place” has been the motto in Mr. Studley’s life, the article goes on to state. He built the cabinet in his spare moments from mahogany, inlaid with ebony, pearl and ivory. The cabinet is of many parts and contains several panels of tools which may be removed and each show the same careful regularity of position inside the cabinet.

Continuing, it stated that the local man was born in Lowell, spending his boyhood in South Scituate, but has lived in Quincy since 17 years of age. The article continued: “He commutes every day from the ‘city of Presidents’ to the Poole factory in Cambridge. A veteran of the Civil War, he is wonderfully preserved and is daily at his bench in the action department of the Poole factory. He is precise in every walk of life and puts his best effort into piano actions, which is one of the salient features of the Poole Piano Co.’s pianos and players. He has been a valued employee for a period of 18 years and bids fair to round out many more.”

This was printed several years ago and now Mr. Studley is resting on his oars and enjoying a respite from active duties, having in his home many handsome souvenirs, unique and delicately made, as trophies of those days when his hands skillfully wrought the things his brain contrived.

Among these are jewel cases of handsome design, a miniature organ, a tiny violin in a case, also a weather vane representative of a soldier in uniform which swings its arms indicative of the direction of the wind, as it operates in the breeze. A mallet made of the wood from the old “Constitution” with metal work for adornments, daintily patterned, is also one of the many things possessed.

Interesting among the souvenirs are several tiny books carved from bone and inlaid in colors. These were carved in a rebel prison where the local grand army man was confined for several months. The bone was from meat provided for his sustenance and his only tool was a pocket knife.

A peculiar feature of his skill for handicraft in that Mr. Studley is a “chip off the old block,” his father having been gifted in a similar manner. The local man has a wooden case for a clock, hand carved and about 110 years old, that was fashioned by his father in a skillful manner, but he was the only one of the sons who inherited the gift.

It is said that a man becomes like the vocation which he pursues through life. It may be that contriving things of beauty, with a nicety of detail and precision, together with the harmony of sounds, is conducive to a fine life, with a tendency to increase the years, being apart from the wear and tear of conflicting emotions. Possibly that is why poise and serenity are predominant traits and the years sit so lightly on this maker of beautiful things.

— Quincy Patriot-Ledger, Sept. 21, 1921