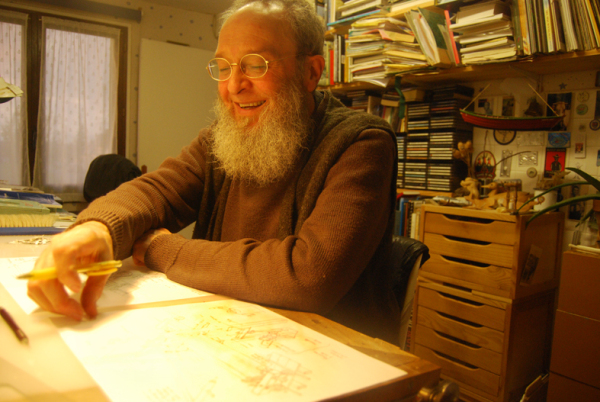

Professional cabinetmaker and author Nancy Hiller’s story is filled with all the places and characters and plots that make up the best biographies (which happens to be Nancy’s genre of choice). The author of five books, including “English Arts & Crafts Furniture” (Popular Woodworking Books), “Making Things Work: Tales from a Cabinetmaker’s Life” (Lost Art Press) and an upcoming book about kitchens (also Lost Art Press), Hiller also writes regularly for Fine Woodworking and her blog, “Making Things Work.” She has taught cabinetmaking, furniture and finishing courses, and she’s a member of the Society of American Period Furniture Makers and a Companion of Ruskin’s Guild of St George.

Nancy’s story begins in 1960s suburban Florida, a life that was soon challenged and broadened by homesteading hippies. There was divorce, a move to a tiny flat in London at the age of 12, boarding school in the English countryside, a strict grammar school, work, rain, boyfriends, work, cold, miles spent commuting on her bicycle, a City & Guilds certificate in furniture making, work she loved, more cold she hated, a move back to the States, a marriage, a divorce, work for others, work for herself, love again and grief; but through it all, passion.

This, from Nancy’s July 20, 2019, “Making Things Work” blog post titled “The Problem with passion.”

The problem is, the popular understanding of passion is seriously flawed. The word passion comes from a Latin verb that means to suffer, undergo, experience, endure. While love is central to passion, passion is no easy kind of love. When we’re passionate about something, we’re driven. We serve our passion by dealing with the trying circumstances and sometimes-maddening fallout that come in its train, every bit as much as by enjoying the satisfactions generated by our pursuit.

From Florida to London

“The salient thing is that my mother was always very handy when we were little,” Nancy says when talking about her childhood in Florida. “She was always doing things around the house, like home-improvement projects such as changing the hinges on the kitchen cabinets and changing the faucet on the sink. She built us a playhouse in the backyard. One of my favorite things was that she tore down the wall between our two bedrooms [Nancy has one younger sister, Magda] and so we had a good example of a woman who wasn’t afraid of using tools.”

Nancy’s father was brought up to be a white-collar professional. He went to law school and then into public relations after time in the Coast Guard.

Nancy grew up in what had been the gatehouse of a once-large estate, later chopped up into subdivisions. It had a Spanish-Colonial-Revival vibe and the outside walls were made of coral. Located on a half-acre plot, it had been landscaped decades earlier by a well-known botanist who brought plants from all over the world back to the estate.

“The scale of our half-acre must have been tiny, but to a little kid it was just this huge world of diverse landscape,” Nancy says. “There was a little bamboo forest with gravel paths and there were all kinds of exotic tropical fruit trees, like carambola, kumquats, loquats and all kinds of oranges and mangoes and avocados.”

Growing up middle class in 1960s America, Nancy says her family’s little patch of land was a revelation. While everything else around her was pre-packaged and filled with preservatives, she witnessed fruit growing on trees first-hand. There was a Norfolk Island Pine tree she loved and a little coral stone cottage in the backyard. For a child, it was near magical.

Nancy grew up playing with Tonka toys, Flintstone building blocks, Mattel’s Thingmaker, Play-Doh and LEGO. At the beach she would build sandcastles, bridges and little channels for water to flow.

“One thing I remember vividly is that I loved rearranging the furniture in the living room and in my bedroom as a little kid,” Nancy says. “So I was always interested in how the inside of the house looked and felt.”

Nancy has always been deeply interested in people and their stories. She didn’t love school, but she remembers enjoying learning about Eli Whitney and his invention of the cotton gin. In second grade she went through a stage in which she signed all her schoolwork with different names –– Amelia Earhart, Calamity Jane –– she’s grateful for the teacher who quietly allowed it.

When Nancy was in fourth or fifth grade, on a cold (for Florida) winter night, her parents brought home some young people who had been sleeping in the local park.

“My parents, to their credit, have always been pretty open-minded,” Nancy says. Her parents were impressed with how these young people, from all over the country, were living free-spirited lives, eschewing conventional ways of earning a living and instead building what they needed, growing their own food, and selling natural foods in a society that seemingly loved the opposite. So intrigued, Nancy’s parents ended up inviting some of the young people to stay with them. And that’s when everything changed.

“There were all these different micro-areas within this half-acre lot and so a couple of the hippies lived in this little stone cottage in the backyard and a couple more built a little wooden house and a couple others built an A-frame,” Nancy says.

The experience was undoubtedly formative. “Whenever that kind of thing happens it certainly makes you realize that the way you’ve been brought up to see the world is not the only way,” Nancy says. “So it was opening up a perspective that I think, in principle, is a good thing.”

Then Nancy’s dad told her she didn’t have to go to school anymore on the grounds that she was being homeschooled. But there was no structure. Nancy filled her time with reading the World Book Encyclopedia and spent countless hours watching and learning from the people living in her backyard.

“It was a revelation to see these guys with a saw and sawhorses building a house,” Nancy says. “It was just so direct. It was amazing to see that you could take tools and simple materials and build a dwelling in which you could live, however crude. That was wonderful for me to see.”

Nancy’s grandparents became concerned. Her sister had already gone to live with them. In 1971, Nancy’s parents separated, and Nancy, along with her mother and sister, moved to a tiny flat in London. Nancy’s grandparents had good friends who lived in London and helped them settle. They then sent Nancy and her sister to a boarding school in Sussex.

Her last year in Florida, with its total lack of structure and discipline, did prove valuable. “After that, I craved structure and discipline,” she says. “I was 12, going back to school and I actually wanted to be there. Had we not had this series of events I might have gone through the rest of my educational years totally unmotivated.”

The boarding school was a Rudolf Steiner school, which meant all the boys and girls had to take sewing classes and woodworking. “It was great because it involved a real contact with material,” Nancy says. She carved a serving platter out of Applewood, which she gave to her parents, and a mechanical toy.

“There were so many things I loved about that school because the boarding hostel was in this fantastic old building and to get to the school you had to walk through part of the Ashdown Forest and just all the smells and the seasons — it was a real sensory awakening for me,” Nancy says. “But I just really missed my mother who was in London. So she finally let me move back.”

Nancy then attended a grammar school operated by “an extremely strict, no-nonsense woman and that was one of the best things that ever happened to me,” she says. She started learning Latin “which it turned out I had a great affinity for,” she says. “It’s very obvious to me now, because it’s architectural. It’s all about building blocks and how they go together. But it was very good for me psychologically because it was like, ‘Here, take this thing, show me you can do it and I will give you praise.’ It was one of the first times in my life someone said, ‘Oh, you’re good at this. You can do this.’ It gave me a feeling of achievement that was new to me. And that’s important for everyone to have.”

Learning the Trade

Nancy doesn’t talk about lifelong dreams. Instead she has always led her life with an air of practicality. As a young adult, she didn’t have a strong sense of direction. “I knew what I was good at and I knew I had to work,” she says.

Throughout high school Nancy worked in bakeries and cleaned apartments and worked at a local sandwich shop with a woman named Hilda.

“Sure it was minimum wage but it was a job and it was money and it was experience and I never thought I was too good for any of it,” Nancy says. “I was always grateful to have someone pay me to work.”

Nancy was accepted into the University of Cambridge but took a gap year and worked as a clerk at the Automobile Association in London. Several years earlier, her mother had gone back to school to study art, met a fellow student and married. Together they had started a remodeling business. Nancy’s father was freelancing as a travel writer, and she and her sister would see him once or twice a year. Nancy lived with her boyfriend in an old building in Islington, east London, that had been condemned but through a community housing association they were allowed to rent an apartment.

At Cambridge, Nancy loved the studying but couldn’t imagine staying there without knowing how a degree in Hebrew and Aramaic would be relevant to a career. She didn’t want to be a teacher and didn’t know what else one could do with such a degree.

“It just seemed, honestly, so self-indulgent,” she says. “I wouldn’t say that now but that’s how it felt to me.” Nancy was there on a government grant, surrounded by people who believed a Cambridge degree and the right contacts were all they needed to succeed. “There was this overwhelming sense of privilege. I loved my tiny, tiny world of study, but other than that, I was like, ‘What am I doing here?’ So I left,” she says.

She went back to the Automobile Association and then, after moving out to the country with her boyfriend, close to where her mother and stepfather then lived, found work in a factory. Having no furniture, she began building some in her spare time. Her stepfather was intensely critical of her work; his harsh and hurtful words prompted her to sign up for a City & Guilds course in furniture making, and she was intent on proving him wrong.

The course was taught in a local community college and she commuted 3-1/2 miles each way by bike daily. Because she had already done her A-levels she was (a) the oldest in the class and (b) exempt from doing course’s required desk work in the afternoons. So she spent her mornings in City & Guild shop classes and her afternoons earning money.

“I set up a ridiculously crude, in retrospect, shop in our dining room and just started making stuff,” Nancy says. She built furniture for her family and neighbors using pine from the local lumberyard. “It was pretty miserable,” Nancy says. “Mainly because it was always freezing and my stepfather was just not a kind person.”

After earning her City & Guilds certificate, Nancy put an ad in the local newspaper, looking for a workshop with a place to live. A man named Roy Griffiths, a Slade School of Fine Art-trained designer, answered. He owned a kitchen company called Crosskeys Joinery that built mostly pine kitchens.

“He drove out to where I lived and I showed him pictures of what I had done,” Nancy says. “I went and visited his workshop. He had bought a Georgian brick house, which sounds fancy but it was just what all the houses were along the river in this little town of Wisbech.”

Roy’s house had come with brick horse stables, which is where he had set up his woodworking shop. There was no insulation, all the windows were single pane and the only heat source was a wood stove.

“It was freezing cold but you know, I had never seen anything like it,” Nancy says. “It was really cool. And he had all this old machinery he had fixed up.”

At first Roy wanted Nancy to build a set of upper kitchen cabinets (what he called a dresser top) as a trial, for pay. But then he simply offered her a job. Nancy left her boyfriend, accepted the job and moved into a room in Roy’s house. But a week later, near frozen, she moved out, choosing instead to move back in with her boyfriend and commute to work by bicycle each day.

“To get to his place was four miles each way, which was not a lot at all and it was all flat but it was always windy and this was through all weather, so it was really, really cold and miserable and always damp, throughout the year,” Nancy says. “But in retrospect I’m so glad I did it because I know I did it and no one can take that away from me.”

Roy served as Nancy’s mentor, not so much in the way of craft but in the way of business.

“I learned from him the importance of being efficient, working efficiently, and designing things for efficient production as well as beauty,” she says. “I mean he certainly impressed on me the importance of good materials and proportions. He was trained as a fine artist, a painter –– he had been to art school, like many of the big names in English furniture making who came from architecture and the world of fine arts. It was before the renaissance in craft training.”

Nancy learned a number of techniques using old, restored, English machinery that are less common in America, such as a tenoner and a sliding table saw. She worked for Roy for about two years. By then, she had decided she no longer wanted to be a woodworker.

“That was my only experience in professional woodworking, and I found it depressingly monotonous,” she says.

Nancy acknowledges that Roy had given her a plum job, building the upper kitchen cabinets that were decorated with custom-made mouldings, and little doors and cubbies. But still, she spent much of her time cutting hundreds of tenons and mortises, and while it was not factory work, it began to feel like factory work.

“I was just doing the same basic processes every day and going out of my mind with boredom,” she says. “Plus, I was freezing all the time. I don’t mean to sound like I’m complaining. That was just the reality. It was depressing. And I was in my early 20s and I had not yet developed the capacity for that kind of routine work I now possess. That is a real learning experience, learning how to just keep doing it. It’s part of growing up in any line of work.” Nancy was desperate to use her brain.

So she and her boyfriend moved, and Nancy got an office job with a travel agency at the University of Reading in Berkshire, England.

“That was a great experience because it was run by this fabulous woman, Bobbie Gass, with whom I’m still friends,” Nancy says. It was an office of women and they became so close that they still stay in touch and even got together for a reunion several years ago.

But eventually Nancy felt an urge to return to woodworking and she found employment at Millside Cabinetmakers, a rural shop located in a converted chicken shed where craftspeople built custom furniture and kitchens. Nancy was the only woman, and there wasn’t even a bathroom when she first worked there. So Nancy used her lunch break to ride her bicycle into town to use a public restroom. “They were nice to me, or they tried to be,” she says.

Back to America

Nancy worked at Millside for about a year and then, for a number of personal reasons, began thinking about moving back to the United States. By this time she had gone through a divorce, and both her mother and sister had already moved back to the States.

“I just wanted to be closer to my family,” she says.

While preparing to move Nancy got a temporary job in the carpentry shop of the Imperial War Museum at Duxford Airbase. There she worked on displays, cabinets and platforms with older, unabashedly sexist male woodworkers who, she says, she got along with splendidly.

Nancy wanted to move to New England, specifically western Massachusetts. But she couldn’t find work there. So she ended up taking a job at WallGoldfinger in Northfield, Vermont, a woodworking company that made architect-designed furniture mostly for financial-market offices on Wall Street and in Boston.

The work, made with architectural-veneered panels, edge banding and highly rubbed-out lacquer finishes, was completely different to what she had been doing in England. “Superficially, the work was absolutely gorgeous, and I learned a lot there about using sheet materials and European hardware.”

While at WallGoldfinger, Nancy fell in love with fellow craftsperson Kent Perelman. They soon decided to leave Vermont together, seeking work in Montana. It was 1988. Nancy was 28. But within the year, they married and moved to Brown County, Indiana, close to where Kent’s parents and sister lived. They opened their own furniture and cabinetmaking business, Credence Custom Furniture. They worked together in their home shop and, after a while, Nancy decided she wanted to go back to university. So she began taking one class a semester while also working in the business. Soon she decided to attend school full time. She won a scholarship, which paid for her tuition. She continued working at Credence, doing design, bookkeeping, client visits and helping with installations and deliveries. The combination of school and work, she says, was good.

Kent and Nancy divorced in 1993. (Kent, who Nancy says was an outstanding craftsman, moved back to Montana, where he remarried, had a family and continued woodworking until he died in 2016 from cancer at the too-young age of 53.) Nancy went on to graduate school with the intent of getting her doctorate and teaching. “But in my first two years of graduate school I realized that an academic life was less likely to be about teaching and much more likely to be about research and bureaucracy,” she says. So after completing her master’s degree, she stopped.

“The one thing I knew is that I did not want to build furniture and cabinets anymore” she says. “I wanted to get an office job.” No longer weighed down by the lack of a degree, Nancy applied with optimism. But it was one rejection after another. “You’re over-qualified.” Or, “You ran your own business, you won’t want to work for someone else.” She became exasperated and, frankly, needed to make money.

She called up a man whose house she had rented with another grad student her first year of graduate school. She remembered his bathroom being almost totally decrepit. She asked him to hire her to remodel it at a reduced rate, because she would be learning as she worked. “I’m not sure whether it was a good thing he said yes but he did,” Nancy says, laughing. “And that was how I got back into the trades.”

Initially Nancy focused on remodeling old houses. She wanted varied work, outside of a solo workshop, allowing contact with fellow human beings. She needed more than working with mute material. But over the years she simply found herself doing more of the woodworking parts of the jobs and less of the remodeling. There was no grand vision. There was no dream. Rather, life happened. Practicality reigned.

“If you said to me, ‘What has driven you?’ I would say it’s really been the need to make a living,” Nancy says. “But also, the desire to be happy and for me, part of being happy is doing what I have to do. So it’s not like a person who feels she knows she has a burning desire to do something in particular. I’ve always been happily motivated by necessity. And when I say happily, it’s a happiness that isn’t always recognizable by everyone as happiness but there is a peace in accepting what is necessary. I know this is not a fashionable way to think in America. But I find it key to happiness. Doing what you have to do and finding happiness in that, finding the bright spots or something that gives you the feeling of comfort or hope or joy or — look at that joint, that joint fits well —I’m happy about that. And I build it up out of little, little things.”

Nancy started her own business, NR Hiller Design, in 1995. She incorporated a few years later at the advice of her accountant.

“I didn’t want to be self-employed,” she says. “It just seems so scary to me.” But she leans on Mark Longacre, her partner, who also is self-employed (Mark Longacre Construction Inc.) and has been for most of his adult life. “It helps to have somebody with whom you can discuss the problems and challenges,” she says.

Also helpful is that Nancy and Mark have built and become part of a network, made up of customers who have become friends; employees (Mark has three and Nancy says they’re as close as brothers); colleagues; acquaintances met through research and at talks; readers; editors; students and more. This larger community of like-minded individuals, this connectedness, has helped ease the anxiety that inevitably comes with self-employment.

Nancy knew of Mark the same way you’re aware of other people in your larger field who also live in your town, she says. They first ran into each other at an appliance store where they had both gone independently to look at appliances for their respective clients. “It was shortly after my first article in Fine Woodworking had been published and the local paper had written a story with a picture of me. He said, ‘You’re Nancy Hiller, aren’t you? I recognize you from your Fine Woodworking articles.’ And I said, ‘Well, there aren’t articles, plural, there’s only been one.’” She then asked, “You’re Mark Longacre, aren’t you? I recognize you from the article the paper did about you.”

At the time they were both involved with other people. For a few years they would run into each other every so often. “I always thought he just seemed like a nice, capable, kind, down-to-earth person,” Nancy says. Nancy and Mark both split up with their respective partners and on the night before Mark’s 50th birthday, Mark called Nancy and invited her to dinner. That was their first date, in 2006. They’ve been together ever since.

Although Nancy never wanted to be a mother, she says she was given the extreme privilege of becoming a stepmother to Mark’s brilliant son, Jonas. “I was lucky,” she says. “I was just so lucky to walk into a relationship in which there was this beautiful, intelligent, self-motivated learner who was just endlessly curious.”

That curiosity is, unfortunately, what ended Jonas’s life on Jan. 2, 2014, at only 15 years old. Described by many as an old soul and deeply curious about the word around him, Jonas was interested in everything, from robotics, advanced calculus and writing software to Latin, constructing languages and reading (at the time of his death he was reading Douglas Hofstadter’s “Gödel, Escher, Bach: An Eternal Golden”). He adored spending summers at Camp Palawopec and was keen on learning primitive survival skills. He was considering a career in computational linguistics.

Nancy was the one who discovered Jonas on the night he died. Out of simple curiosity, a desire to better understand how the human body works, Jonas had experimented with what’s commonly called the “choking game.” It involves self-strangulation as an experiment, to feel what it’s like to have oxygen rush back to your brain after it’s been cut off. Only Jonas died before he could un-strangle himself.

Nancy says she believes in the importance of telling this part of her life story for no other reason than to share the light of Jonas with others and to raise awareness about the game. “I was very lucky to get to know him and be a part of his life.”

Finding the Bright Spots

These days Nancy works on her own, although she has had employees in the past (see her post “Daniel O’Grady is in the house” here). Her work is now so varied, employing someone would be difficult. In addition to shop time Nancy’s writing, designing and meeting with clients. Flexibility is important and, Nancy notes, it’s often nice to not carry the heavy weight of responsibility that comes with being in charge of someone else’s livelihood.

At the end of last year Nancy spent three months building and installing a couple of kitchens. The installation process in particular is intense, physical work, manhandling cabinets made out of 3/4″-thick veneer-core plywood with solid face frames while scribing them to fit walls and floors. There is travel time between the client’s houses and Nancy’s shop, along with ongoing business-related work: preparing quotes for customers, design work, drawing and more. For book projects, Nancy might block out three weeks at a time to focus on writing, attending to small parts of the business in the evenings or on weekends. And then, it might all reverse. She’ll spend her days in the shop, using her nights and weekends to write her next blog post for Fine Woodworking.

“I find the more variety I have the more hours I can work because changing is refreshing,” she says.

It is here, though, that Nancy’s lifelong work ethic deserves praise. I ask her about it. “I just have this deep-seated admiration for people who work hard,” she says.

Nancy isn’t sure where this came from. Perhaps England. Perhaps hidden in the prayers she had to recite at school. Perhaps, paradoxically, she says, from the hippies. “Even though people think of hippies as layabouts, what I saw was a lot of work being done.”

Growing up in the 1960s, Nancy says as a child, she associated working hard with being a man. “I didn’t aspire to be a man,” she says. “I just thought, well, those are the people who have respect in our culture. They were the people who were recognized in public life and they were the people who did important things with a capital I. It’s hilariously ironic because look at women’s work! It’s just that women’s work hasn’t always been appreciated (and is still vastly underappreciated) in American culture.”

And it’s not that Nancy loves working for its own sake. “It’s that I’m building toward something,” she says. “There’s a tangible result, a satisfaction, and I feel connected to the world, and I feel like I have a purpose. All of those are important motivators for me.”

This, of course, all ties back into Nancy’s definition of passion: While love is central to passion, passion is no easy kind of love.

Nancy finds herself thinking a lot about the tiny bright spots in her life. It’s easy to feel depressed right now, she says, by politics, ecological realities, the pandemic. “So much of it is just psychological,” she says. “It’s like playing on the monkey bars, going from one rung to the next. You just keep going. And it’s weird because I know that I’m depressed a lot of the time lately. I recognize that clearly but there’s also kind of an underlying happiness at the same time and it comes partly from acceptance and partly from finding joy in tiny things and not needing everything to be perfect. I think there’s happiness to be found in kind of letting go of trying to control your fate at every level of your life because you can’t. Or, at least, I can’t, and I don’t know anyone who can.”

When we’re passionate about something, we’re driven. We serve our passion by dealing with the trying circumstances and sometimes-maddening fallout that come in its train, every bit as much as by enjoying the satisfactions generated by our pursuit.

And so Nancy spends time at home, with Mark, and in her shop with her shop cat, her dog, Joey, often by her side. She reads. At the time of our interview she was reading a biography of Thoreau. She finds reading about the obstacles humans overcome both helpful and fascinating. She likes gardening (but despises the chiggers). She likes the changing of the seasons, the way the soil, plants, animals and trees change with them. She loves to laugh. Nancy Hiller has the best laugh.

Not too long ago Elizabeth Knapp, managing editor at Fine Woodworking, read Nancy’s “The problem with passion” blog post. Liz asked Nancy if they could publish it in the magazine (Nancy said yes). It’s easy to see why. It sums up Nancy’s life so beautifully but with that air of Nancy practicality.

Doing what you love for a living demands that you cultivate a larger understanding of loving what you do, she writes. And that is why, because of everything, despite everything, Nancy can say, she’s happy.

— Kara Gebhart Uhl