Editor’s note: For the next several weeks, we will feature some of our favorite columns from “Honest Labour: The Charles H. Hayward” years, along with a few sentences about why these particular columns hit the mark.

If you know anything about me, my primary reason for selecting this 1937 column as a favorite will be readily apparent. But beyond the (perhaps) obvious, I find it’s important we be reminded from time to time to really look at what’s around us rather than just moving through it, and to be constantly learning.

— Fitz

Mind Upon Mind

“You can’t make bricks without straw” is an old adage which we have taken from the woes of the Israelites, groaning in bondage to the Egyptians. Every “maker” that is to say, every craftsman, artist, writer—learns it by sheer necessity. There is a material he needs just as much as the immediate timber or stone, paint and ink with which he works. It is a remoter thing which he has to glean from the world about him: ideas and knowledge garnered in to render the skill of his hands effective. It is no good being taught how to do a thing if he does not observe and extend his learning. A man may be taught how to make a perfect joint, but it takes knowledge and experience to learn when and where to use it; just as a man needs more than a technical knowledge of drawing and painting to become an artist, more than a knowledge of how to frame sentences to become a writer.

***

There is a commerce of ideas continually going on in the world. Nowadays beginners still have to learn the technique of their craft from older men, just as they did in the craft workshops of the past, and they learn by carrying out instructions as exactly as possible, copying their teachers as closely as possible. We are told by Vasari that, when Raphael was learning to paint in the workshop of Pietro Perugino, “he imitated him so exactly in everything that his portraits cannot be distinguished from those of his master, nor indeed can other things.” And later, when he had left the workshop and was working on his own in Florence, the centre of inspiration to all the great Renaissance painters, we still find him studying the works of other men. “This excellent artist studied the old paintings of Masaccio in Florence, and the works of Leonardo and Michelangelo which he saw induced him to study hard, and brought about an extraordinary improvement in his art and style.…It is well known that after his stay in Florence, Raphael greatly altered and improved his style, and he never reverted to his former manner, which looks like the work of a different and inferior hand.” So says Vasari, who was no mean judge.

***

The man who is going to be of any account will be the man who makes best use of his powers of observation to enlarge the equipment of his mind. As Professor Gilbert Murray says somewhere: “The great difference, intellectually speaking, between one man and another is simply the number of things they can see in a given cubic yard of world.” The other day I heard an intelligent youngster talking to another about some silver birch trees he had noticed down the road. “I didn’t see them,” his companion said. The first boy looked at him astonished. “D’you go about half dead?” he demanded. It is what we are all apt to do at times. We are occupied with our own thoughts and forget to look outside ourselves till very often necessity, which, like the Egyptians of old, is a stern taskmaster, forces us to it. For to the craftsman in any medium, ideas built upon observation of the work of other men as well as that of nature are a necessity, if they are to be creative workers in any sense of the word.

***

The influence of mind upon mind is extraordinary. In a law case lately in which a famous actress was involved the judge had once more to enunciate the old legal axiom that “there is no copyright in ideas.” Ideas are constantly being exchanged, seized upon and developed. They are the common currency of mankind, the means by which, consciously or unconsciously, we learn from one another. But to be of any value they have to be carefully submitted to the bar of our own judgment and reflected upon. Only by so doing can we extract the essential “straw” from them which will help us to make bricks of our own. The idea which is simply annexed becomes weakened in transit. But if it is absorbed, wrought upon by the individual mind, it gathers new elements. We can see the process at its best in Shakespeare—the man who took his plots from old plays and stories, and so wrought upon them with his mind that they became charged with greatness, suffering “a sea-change into something rich and strange.” A man who went about with open eyes and mind indeed for the passions and the foolishness of men, their dreams and futile longings, their littlenesses and greatnesses, observant of all the country sights and sounds which weave them-selves into the music of his verse: the “daffodils that come before the swallow dares, and take the winds of March with beauty.”

***

It may seem a far call from the ordinary man in a small workshop to Shakespeare. But the mystery of it is that the elements of the craft are the same, even though the results may be so different. Like Shakespeare we have to get our “straw” where we can find it, and the more we search for it the less likely are we to belong to the “half dead,” the men who neither see things nor do things but become as standardised as the window frames they put in houses. Shakespeare filled his mind with the rich material of the living world, pondered it and used it as the fuel of his genius. Raphael, for ever learning and studying even when he had fledged his wings, became one of the greatest masters of the Italian Renaissance. The quality of genius is not in every man, but there is a quality which is the very essence of himself, which is able to express itself in his work if he will give it the wherewithal to feed upon so that it may live. The trouble with us nowadays is that there is so much to distract us that we are apt to fritter our time away on nothing. But on the other hand we have opportunities for widening and enriching our knowledge with the old craftsmen might well have envied. And now that the holiday season is approaching, and those of us who would ordinarily be tied to office or workshop will be moving about the country more freely, we might well keep our eyes and ears open a little more. A friend who is a well-known artist once told me of a visit he had paid to Arundel Castle, talking in detail of the many beautiful pieces of furniture he had noticed on his way through the rooms. I, who had also visited Arundel Castle, remembered not a quarter of it, but I had such a lesson in observation from his eager descriptions that the next time I intend going with a pair of eyes in my head. For it is not only the looking but the way we look that counts.

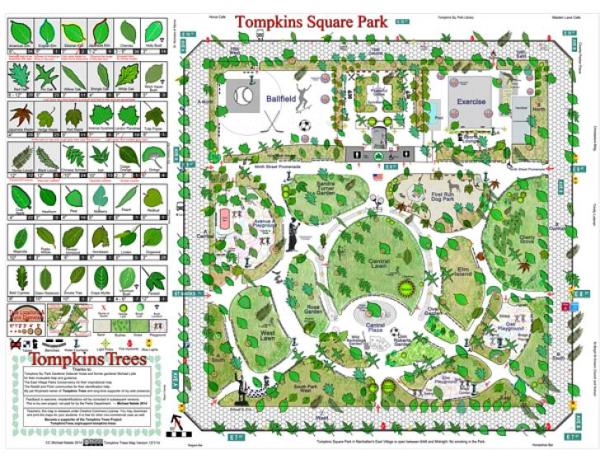

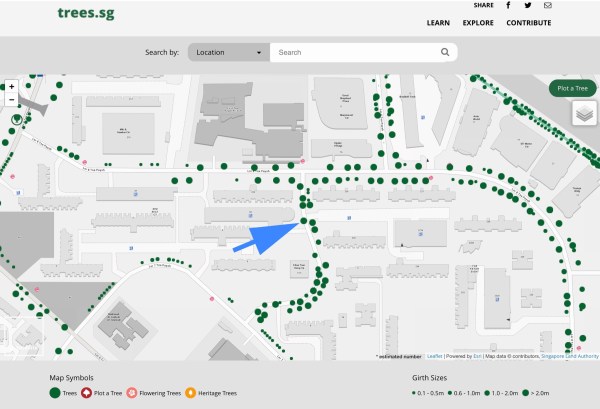

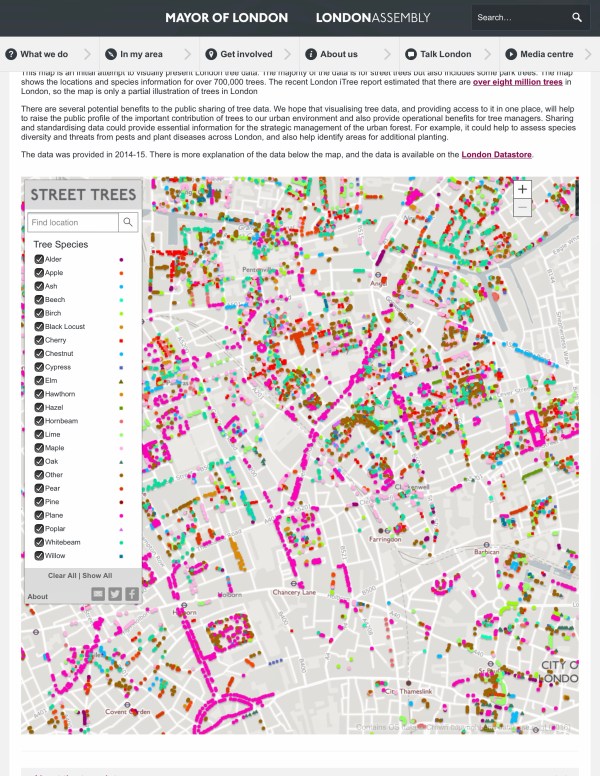

From the photo gallery you can see the leaves and flowers. These are some of the options to be found on street tree maps. Singapore’s map can be found

From the photo gallery you can see the leaves and flowers. These are some of the options to be found on street tree maps. Singapore’s map can be found

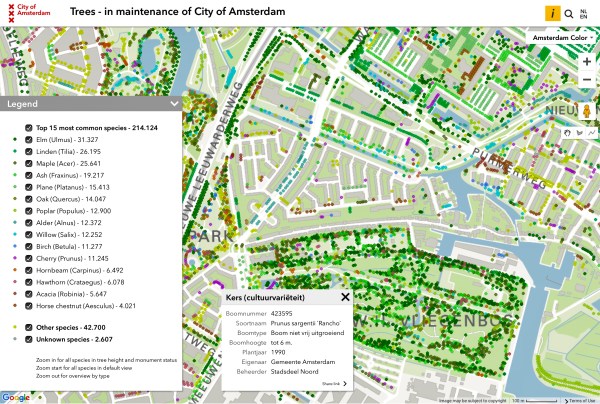

Another set of trees you might find in a map are heritage trees. Seattle’s tree map includes heritage trees (in orange) and reminds the viewer the trees may be on private land, in a park or be a street tree. As this map notes, a heritage tree is “distinguished by botanical, historic or landmark significance such as size, age or uniqueness.” Seattle’s map can be found

Another set of trees you might find in a map are heritage trees. Seattle’s tree map includes heritage trees (in orange) and reminds the viewer the trees may be on private land, in a park or be a street tree. As this map notes, a heritage tree is “distinguished by botanical, historic or landmark significance such as size, age or uniqueness.” Seattle’s map can be found