This is an excerpt from “The Wordworker: The Charles H. Hayward Years: Volume I” published by Lost Art Press.

The back iron of the plane is of the utmost importance. It will often happen that, because it has not been given proper attention, the plane will not work properly, or possibly not work at all.

The function of the back iron is to control the condition of the shaving that the plane makes. Not that one minds what happens to the shavings, but that, in being removed, they have their effect on the surface of the wood. The power of the arms expended in making shavings is shared between cleaving off the part of the wood from the solid mass and in destroying its stiffness as it passes up into the mouth of the plane. A shaving would not pass comfortably up into the mouth of the plane if it were not fractured on its outside at fairly regular intervals, and it is the function of the back iron to do the fracturing.

If all grain were parallel with the surface a back iron would never be needed (see Fig. 2). It is its slope that causes it to tear out

The breaking off of the shaving not only facilitates the removal of the shaving from the plane, but it does something that is even more important; it destroys the strength of the grain of the shaving, so that the natural tendency for the part that is removed to split off cleanly is checked.

To explain this by analogy, if a slice of a length of deal were chopped with an axe, the fact of the axe acting as a wedge would largely cleave off the piece as at A, Fig. 1. If the part already separated were snapped across by the introduction of a sort of back iron, the liability to split would be greatly lessened, as at B, Fig. 1. If we apply this illustration to the cutting iron and back iron of a plane, we shall see that the work of the back iron is to reduce the tendency to split.

This fracturing takes up a larger percentage of the energy expended than will at first be appreciated. As a consequence, the back iron is set close to the cutting edge only when the mixed nature of the grain renders it specially liable to tear out. Thus, quite a lot depends upon so arranging the back iron that it will give the results required with the most economical expenditure of time and labour. Time spent in planing can be very wasteful.

In planing off stout shavings of deal, the back iron is set well back, say, a full 1∕16 in. If the back iron were 1∕4 in. up, the curl in the shaving would not be sufficient and the grain might split out; probably a bare 1∕8 in. will be the utmost at any time that it will pay to keep the back iron up. One-sixteenth in. will, in practice, be satisfactory for an average run of work, especially so far as the jack plane is concerned. This distance will, however, be too much for material that is inclined to tear out, especially as the finishing stages are approaching. In fact, for a piece of curly grained mahogany, the back iron should be about 1∕64 in. only from the cutting edge.

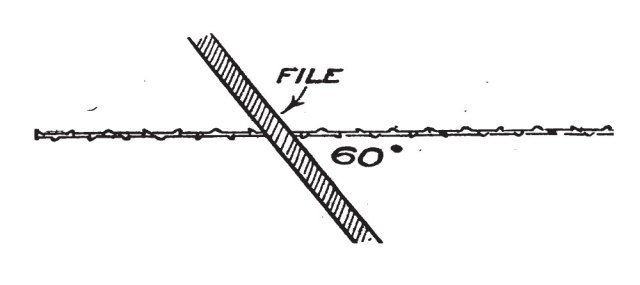

A further important point regarding the back iron will be that there must be no flaws in it, for in the course of time the impact of the shavings against it is liable to cause this defect. With planes that are finely set, a certain slight jaggedness will at length appear along the edge of the back iron. This should be corrected with a fine file.

The back iron must also fit close down to its cutting iron when it is screwed in place; if there is the slightest space anywhere shavings will clog so that the plane will work both slowly and badly. Another point to remember is that the back iron should be a trifle round, so that the distance back from the cutting edge is parallel (for the edges of all cutting irons must also be slightly round).

— MB