Early visitors to the new western cities of America were willing to travel by coach, wagon, horseback, boats and on foot to see and report on the westward growth of their new and independent country. They kept detailed diaries and turned their experiences into published travelogues. A minister would include the social aspects of the settlements, whereas an engineer would take note of the topography, soil conditions and geology. Publishers of almanacs and directories recorded annual growth of population, commerce and manufacturing.

Pittsburgh was, as an early traveler from Boston noted, the “key to the Western Territory.” This was especially true for travelers from New England, New York and the Mid-Atlantic states, for Pittsburgh was the stopping point to resupply and get repairs before continuing their overland westward journeys. Once steamboat travel was available, Pittsburgh was the embarkation point to begin a trip on the Ohio River and onward to the Mississippi and Missouri Rivers.

David Thomas (1776-1859) was a Quaker from Cayuga County in western New York. Traveling by horseback, he departed his home in the summer of 1816 on a trip that would ultimately take him to western parts of the Indiana Territory. He kept a diary and made note of the geology, agriculture, wildlfe, commerce and industry he observed during his travels. His notes and observations were published in 1819. He arrived in Pittsburgh around June 7, 1816, and described it as such:

Wraught Nails to Cut Nails

The new towns and cities of the “Western Country” needed a huge supply of well-made nails and they needed them fast. By 1807 there were four nail factories, all worked by hand. In 1811 Charles Cowen opened a slitting and rolling mill that included the manufacturing of nails. By 1814, the Pittsburgh Iron & Nail Factory was owned by William Stackpole and Ruggles Whiting, both originally from the Boston area. Their factory was steam powered and they installed Jacob Perkins’ patented cut nail machines. Thomas visited the Stackpole & Whiting rolling mill and nail manufactory and observed the manufacture of cut nails.

Jacob Perkins invented the nail machine in 1790 and patented it in 1795. His invention was reportedly able to cut 500 nails per minute.

An advertisement in a Lexington, Kentucky, newspaper, circa 1815, for goods from the Pittsburgh Iron & Nail Factory.

The Stackpole & Whiting mill was located at the corner of Penn Street and Cecil Avenue. In 1818 they bought steamboats at foreclosure and began to build their own boats. They went into bankruptcy in 1819 and relocated their boatbuilding business to Louisville, Kentucky. The rolling mill was later taken over by Richard Bowen.

The Mechanic’s Retreat

In 1815 an outlet tract (land cleared for farming) across the river in Allegheny Town was subdivided and developed as a residential area for workers employed by some of the early industries located a short distance away along the banks of the Ohio River. The area was bounded by Pasture Lane (now Brighton Road) and the North Commons (now North Avenue). The houses were modest in an otherwise undeveloped rural setting. Mechanics Retreat Park, at the corner of Buena Vista and Jacksonia streets, is a small remnant of the original development.

Also in 1815, Mr. James Jelly opened a three-story steam-powered factory for the carding, spinning and weaving of cotton. The next year an advertisement for a different kind of Mechanic’s Retreat ran in a local newspaper.

The Quality of Local Goods

Thaddeus M. Harris, a Unitarian minister from Boston, along with several companions, left his home in the spring of 1803 to visit the territory northwest of the Allegheny Mountains. His party arrived in Pittsburgh on April 15. After experiencing an eight-day journey over the mountains he remarked about the expense of moving goods overland from Philadelphia and Baltimore. The expense of transporting heavy goods, such as furniture, might cost more than that of the furniture.

As the business class gained wealth they sought to furnish their homes with high-style furniture as was made in Philadelphia and Baltimore. Skilled craftsmen from both cities, as well as those from other cities and towns on the Atlantic Seaboard, moved to the new western cities seeking the same opportunities as other new settlers. In 1803 Harris noted the quality and woods used to make furniture.

Fourteen years later, Cramer’s Magazine Almanac of 1817 provides more detail about the types of furniture being made. One indication of the growing wealth of some customers, and cabinet makers, was the use of mahogany for furniture. Mahogany was transported by steamboat from New Orleans, a river distance of almost 2,000 miles.

The Mechanics

Before city directories were published there were other publications touting the growth of the western cities. Matthew Carey’s American Museum, or Universal Magazine provides this accounting of the mechanics working in Pittsburgh in 1792:

Zadoc Cramer, publisher of an annual almanac, reported $33,900 worth of goods were made by the carpenters and furniture makers of Pittsburgh in 1803.

By 1810 Pittsburgh was established as a manufacturing center and the population was approximately 4740. The population grew to 8,000 in 1816 and to 9,000 in 1819 (the population in outlying areas was not always included). Pittsburgh was incorporated as a borough in 1816 and the following year a survey of the manufacturies operating in the city was commissioned. The account was published in the city directory fro 1819 (only woodworking and related trades are shown below:

Three cabinet makers had advertisements in the 1819 city directory. Joseph Barclays’s ad included a pointing finger (manicule) causing some irregular, although eye-catching, spacing. In the directory William Crawford’s ad was turned 90° sideways, a technique to allow more text and also to attract interest. Liggett’s ad includes an illustration and was likely the most expensive. The illustration has a roomful of furniture at the top, including a disassembled bedstead with headboard, posts and rails. Liggett was also offering mahogany furniture.

It can be difficult to determine how a 19th-century craftsman and his business fared. City directories were not published each year (especially in the earliest years of settlement) and some directories only listed householders. We do know not every person in a town was counted or listed.

A craftsman might move to an outlying area and have a thriving business and not be documented in the Pittsburgh directory. It also wasn’t uncommon for a craftsmen to move elsewhere for a better opportunities, to change to a different type of employment and there’s also the ever-present disease and death that ended a career. Efforts weren’t usually made to collect directories and other ephemera until decades later when copies might already be scarce.

Here’s what a quick search revealed about the cabinet makers in the three advertisements:

John Barclay appeared in the 1815 and 1819 directories only.

William Crawford was in the 1819 and 1826 directories only.

The Liggett family had the longest presence in the city. John Liggett was probably the father and James was his brother or son, both were cabinet makers. A third Ligget was Thomas, likely John’s son (initially listed a cabinet maker and subsequently listed as a carpenter) had the longest series of listings. All three started at the same address, south side of Second Street between Wood and Market streets.

James, the advertiser, was in the 1815, 1819 and 1826 directories. The 1819 listing shows him just a short distance from the Second Street address. John Liggett was in the 1812, 1815, 1819 and 1826 directories. Thomas, initially listed a cabinet maker and subsequently listed as a carpenter, was in the 1812-1826 directories with his last listing in the 1837 directory. He was not in the next directory from 1841, but may have worked beyond 1837, giving him at least a 25-year run.

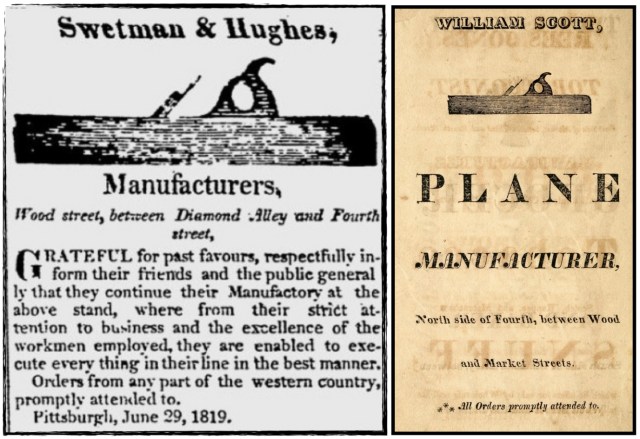

William Scott had a long career as a plane maker, possibly starting before 1807 and at least until 1839. Charles W. Pine, Jr. wrote an article about early Pittsburgh plane makers and you can find that article here.

The Swetman & Hughes ad ran in the Pittsburgh Gazette. I used Pine’s article to get a lead on the short-lived partnership of Swetman & Hughes. The partnership of James Swetman and William P. Hughes employed three other plane makers: Thomas Clark, Samuel Richmond and Benjamin King. None of the five plane makers show up in the 1815 city directory and only Thomas Clark was found in the 1826 directory for Pittsburgh. Nothing more showed up for Samuel Richmond, but there are some details available for Swetman, Hughes and King.

James Swetman was born in England, arrived in America in 1809 and worked in Baltimore with William Vance until 1816. The Pittsburgh parnership of Swetman and William P. Hughes lasted about two years, until 1820. Swetman then made his way to Montreal and is believed to be the first plane maker in Canada. The Tools and Trades Society has an article about four Bath minor plane makers and includes a short history of James Swetman (you can read the article here).

William P. Hughes was originally from Maryland and likely met Swetman while they were both in Baltimore. After the partnership was dissolved, Hughes moved to Cincinnati. He appears in the 1829 and 1831 city directories, each time at a different address. In subsequent listings, if it is the same person, he had moved on to other occupations.

Benjamin King, also originally from Maryland, was much more successful in Cincinnati. He is listed as a plane maker in the city directories from 1825 to 1844. Beginning in the 1831 directory and onward, he was listed at the same address, on Abigail Street, between Broadway and Sycamore, indicating he found a level of stability in Cincinnati.

Economic Distress and the Formation of a Cooperative

In 1815, after two years of war with America, the warehouses of British manufacturers were bursting. There was a rush to sell these goods, even at a loss, and ship them to America. American markets, with little or no protective tariffs, were flooded with British-made products. One group of manufacturers hit hard were the cotton mills. James Jelly’s cotton mill (across from the advertised Mechanics Treat tavern) began operation in 1815. Soon, his mill, along with more established mills, were struggling to compete with imported textiles. Overall, despite the influx of imported goods, Pittsburgh continued to grow, although moderately, until the Panic of 1819.

In this front-page notice from the February 1819 edition of the Pittsburgh Weekly Gazette a group of craftsmen endorsed sandpaper made by Thomas Bryan. They emphasized it was equal to any imported sandpaper. This was an important means of offering support to a fellow craftsmen, and it telegraphed to the public that good-quality materials were being used in local workshops.

The numbers employed by the city’s manufacturers dropped from 1,960 in 1815 to 672 at the end of 1819. The population fell from about 9,000 in 1819 to 7,248 in 1820.

A farmer wrote to Cramer’s Magazine Almanac in a letter dated July 19, 1819. It was published in the 1820 edition of the almanac:

The farmer had read about an Agricultural Society that might serve as a remedy: “The plan designs to make the society a means of promoting domestic manufacturers as well as to patronise a better system of agriculture.”

The idea of forming a cooperative for the goods made by individual craftsmen and manufactories was also percolating. In April of 1819 the Pittsburgh Manufactory Association was formed. Samual Jones reported on the Association in the 1823 city directory:

The association opened a large brick warehouse on Wood Street between Front and Second streets. In an article about the beginnings of cooperatives in the Pittsburgh area, John Curl detailed the products sold and the the early success of the association:

Samuel Jones (in the 1823 directory) had a few more things to say about buying local:

First Impressions Are Important

David Thomas, the visitor from 1816, made note of two characteristics of the people of Pittsburgh.

First, the vile language:

And, several paragraphs later:

I lived and worked in Pittsburgh for a few years and can attest to the kindness and generous nature of the citizens of the Burgh. As for vile language, I heard none unless a few Ranger fans had the temerity to come to town for a match up with the Pens.

— Suzanne Ellison

A detailed map of Pittsburgh from 1830, courtesy of the University of Pittsburgh Library System can be found here.