Read “Meet the Author David Finck (Part 1)” here.

As a young child, David Finck, author of “Making & Mastering Wood Planes,” took ceramics classes through Pittsburgh’s parks and recreation department and loved it. At UC Berkeley he discovered a pot shop that was open to anybody to use. And so, for a second time in his life, he started to get really into ceramics. During his junior year David was regularly showing up to class spattered in mud and clay. A woman sitting next to him noticed, as she was also interested in ceramics. She told him about some summer workshops she had taken in Mendocino, and how she discovered she liked making the carved wooden implements and tools more so than the ceramics. While in Mendocino she inquired about a woodworking school and was told one had recently started up, in Fort Bragg, run by a guy named James Krenov.

David was intrigued. He recognized Krenov’s name from his father’s bookshelves. And because David was a California resident and the school was run through a community college, the program was essentially free.

“Now my plan at that point was to get through one last year at Berkeley and then go back to West Virginia and hang out in the woods with my folks and make guitars,” David says.

But now his head was spinning. Krenov was a well-known woodworker and David knew he’d be better off learning some new woodworking skills. It never occurred to him at the time to go to guitar-making school. But even if it had, it wouldn’t have been practical. Few existed, and the ones that did were expensive. So David bummed a car and drove up to Krenov’s school.

“I was swept up in what was happening,” he says. “There was so much amazing work being built. I hung out for a full day and talked to people. The atmosphere there was really good. There was a lot of energy and Krenov was there all the time and I just remember feeling so magnetically drawn to the whole atmosphere. I was blown away by the quality of the students’ work. But at that point I just had one kind of half-assed guitar that I made on the seat of my pants, so I had no idea how I was going to get into that school.”

Turns out Krenov took the community college part seriously and always kept a few spaces open for someone who was retired and someone who was young and promising.

“And then the other 20 spots were going to people who were, you know, amazing,” David says. “Krenov had created this pent-up demand for his teaching through his books so you had people that were steeped in his writing who had been hard at it for 10, 15, 20 years. People would come from all over the world to study with him. So I was very anxious to go to school there.”

David put together a portfolio. “It was one photograph of my crummy guitar sitting on rumpled blankets on my bed,” he says. “And I wrote a pretty maudlin letter about why I should get in.”

David visited a second time and spoke with Krenov. This time, he brought his guitar and showed it to Krenov in the parking lot.

“That turned out to be lucky because he had a soft spot for guitar making,” David says.

David was placed on the waitlist, but pretty quickly got a spot. “I was over the moon,” he says.

Back in West Virginia, in between Berkeley and Krenov’s school, David panicked. “I remember thinking, Oh my god. I don’t know anything about furniture making. I’ve never cut a dovetail in my life.”

But, it turns out, the structure of the class was good. After spending four to six weeks on fundamentals, students were given the freedom to continue with fundamentals or move on to more sophisticated projects. David thrived. And at the end of the first year, he wanted to stay.

“I was very lucky to come for another year,” he says. “That was an incredibly talented class and there ended up being six people that wanted to stay – and at that point they had never taken more than four. Everyone is just so real and good-hearted there. They couldn’t be bureaucratic about it. They had to bring us all in and we were having a roundtable and discussing, and I remember sitting there and talking with my bench mate who had come from north of the Arctic circle. And we were like, ‘Oh, Dave, you should be the one’ (his name was David, too) and he was like, ‘no, Dave, you should’ and finally they were like, ‘Oh, we’ll just keep everybody.’ It was really sweet. But of course that meant two other students couldn’t come for their first year. But at any rate, it was such a great class. It was very much a highlight of my life – being exposed to a lot of incredibly unique people and Krenov himself and associate teachers.”

During his second year there, David also met his wife, Marie Hoepfl.

“She was a student in the class and I could gaze longingly at her while at the workbenches,” he says, laughing. “We hung out and got together pretty quickly.”

At the end of David’s second year he moved back to West Virginia and Marie began her second year at Krenov’s school. They ended up spending that year apart, then Marie moved to West Virginia to be with David.

Galleries & Shows

Marie was a middle-school shop teacher at the time, and one of her motivations in going to Krenov’s school was to be a better woodworking teacher. After moving to West Virginia she taught shop for several years across the river, in a rural high school in Woodsfield, Ohio. But as the population dwindled and students moved away, the woodworking program was shut down. Marie took that opportunity to go to graduate school, get her doctorate and eventually provide teacher training in technology education.

While Marie was teaching and in school, David worked as a speculative woodworker (you can view examples of his work here). Krenov had set him up with a gallery in Long Island.

“It was pretty exclusive and an awesome place to have represent you at that time,” David says. “But instinctively, I don’t have a great flair for design. I think to make it as a speculative woodworker you’ve got to have so many things lined up in your alley and that was probably my major weakness. So I was batting like 500 with speculative gallery sales, which ain’t good enough. You’re spending half your time not getting paid and after three years I was getting kind of desperate.”

David shared a shop with his dad, and for a while David and Marie were living in the woods on David’s parents’ property in a 10’ x 25’ garage-type structure lined with books on both sides, with a woodstove. They lived there for about five months then moved to New Martinsville, West Virginia, living halfway between Woodsfield, Ohio, where Marie taught, and the shop David shared with his dad. Once Marie lost her job and started grad school in Morgantown, West Virginia, they rented a house two miles away from David’s parents’ place, where David lived during the week, and they rented an apartment in Morgantown, where Marie lived during the week. For four or five years they made this living arrangement work, coming together on the weekends.

Needing to find other outlets to sell his work, David started exhibiting at American Craft Council shows, selling what wasn’t selling in the galleries, and in the process earning himself some nice commissions. He also developed a wholesale item, a limited production run of an Asian-looking lantern – a good bread-and-butter item, he says. He was becoming more well-known, with more commissions coming from around the state, including a substantial commission to design and build seven major pieces for a Roman Catholic church undergoing renovations in Parkersburg, West Virginia. The job, which included an altar, presider’s chair, lectern and more, took more than 18 months to complete.

By this time Marie had finished her doctorate and was job hunting. Their first daughter, Ledah, was born. Marie found a job in Pittsburg, Kansas, and in 1994, when Ledah was three months old, the newly made family of three moved.

Writing ‘Making & Mastering Wood Planes’ While Parenting

Marie loved her new job and David became a stay-at-home dad. Marie would get home from work fairly early and the two would switch. Marie would watch Ledah while David worked in his basement shop.

This continued for three years, during which Willa, their second daughter, was born in 1996. But Kansas did not feel like home. David and Marie missed the mountains. Marie got a job at Appalachian State University in Boone, North Carolina, and they moved back east.

Now with two kids in tow, David was struggling to keep his hand in the craft while also caring for a baby and a toddler. By now he had been teaching the Krenov approach to woodworking in adult education classes at colleges and through craft centers for 11 years. He had gained a lot of experience teaching planemaking, specifically. It was always a popular course and folks were encouraging him to do a more in-depth study of the topic.

“So I just hatched a plan to basically give my weekend workshop in book form with as much detail as I could muster. Whenever the kids were napping or being quiet that was something I could do in the basement shop,” he says. I think it took a better part of a year to do the writing and all the documentation and photography and sketches, and then I ran through five different proof readings with what I call my egghead woodworker friends, just educated people that had either all gone through the Krenov program or were just woodworkers and highly educated. So I got a lot of great feedback from them as well and distilled all that.”

Sterling bought the book. He sent it and, outside of style, his editor had one edit regarding a comma that turned out to be a misinterpretation.

“It was pretty amazing,” David says. “It was already very well vetted when it went off. They took care of it for seven or eight years. And then they finally decided that everyone who wanted to make a wooden plane in the world had done that and their sales were declining so they just gave it back to me.”

David started getting emails from people asking how they could get the book and when was it going to go back in print. Because he had all the computer files, layout, artwork – everything – David decided to self-publish, working directly with a printer in Ashland, Ohio.

“And that worked well for years until I got tired of it,” he says. “Just dealing with the printer and then dealing with boxes and boxes of books and stuff around, and then just filling orders kind of on a daily basis – it’s not primarily where I wanted to be spending my time. So when the final printing dwindled down it struck me that Lost Art Press might be interested in it. I mean, after all, Chris provided the blurb for the back cover. And he showed no hesitation. It was just really wonderful. And I really appreciate the hardcover version, and the nicer-quality aspects of the book as well.”

The Suzuki Method & The Forget-Me-Nots

During this time David was still woodworking in Krenov’s spirit, as he describes it, and building about one guitar a year. Once or twice a year he’d have a booth at a show. He kept teaching, eventually hosting classes at his home shop, which meant more pay and no travel.

Once he finished “Making & Mastering Wood Planes,” David began searching for things to do with his daughters, now 2 and 4. He found a woman, Nan Stricklen, who taught Suzuki violin lessons and so they started taking lessons, along with a 3-year-old friend, on a weekly basis. Ms. Nan did a marvelous job with the younger kids and had a total knack of making it fun while getting information across, David says.

“I really did enjoy working with them on stuff and the Suzuki violin philosophy encourages that quite a bit where the parent acts as a teacher, especially in the younger stages,” David says. “So it was very much just quality time together, playing with the instrument and trying to get across the concepts the teacher was working on. And we were just consistent. We never pushed it hard or anything like that, but we got our 10 or 15 minutes in most every day for years.”

Four or five years in, David began introducing the girls to regional folk music, “just kind of the heart of Appalachia Old-Time music,” he says. “There was just music everywhere, especially at all the folk festivals all throughout the summer. So they had a lot of exposure to that, especially when they were little. And then, somehow or another, before I knew it we had a family band.” David backed up his daughters and their friend on his guitar. The Forget-Me-Nots played Celtic music throughout western North Carolina.

“I never had a performing gene and this was definitely not a case of stage parents, but rather we’d just play in the park and people would see us and the next thing you know we’re giving a little concert in the park, and then somebody asks and before you know it we were doing 30 or 40 gigs every summer. These girls had a full-fledged band.”

The girls continued to play through middle and high school, with both daughters attending University of North Carolina School of the Arts (UNCSA) their senior year – a pivotal time for both of them.

“All the way through they were kind of standouts for music for what they did, but as far as classical music goes, which is their primary focus, it’s like, OK, you’re in the top 1 percent – that’s wonderful, but that doesn’t get you a job. You’ve got to be in the top .001 percent to win an audition and be in a symphony, and be even better than that to be a soloist. But that takes the tiger mom or dad and long hours of practice, and none of us were willing to do that. But when they got down to UNCSA, and really perceived all that in a visceral way, they made that decision on their own. That was the year that both of them started practicing three to four, five to six hours a day. They just skyrocketed. And they had great teachers.”

David’s First Violin

In 2011, David’s dad passed away. A year later, Ledah, still in high school, won a collegiate violin competition, giving her the use of a really fine, contemporary-made instrument on loan for a couple years. Now those years were ending and Ledah needed another good instrument.

“I didn’t have the arrogance or naivety to think that my first violin would fit the bill because it’s just an incredibly sophisticated craft in so many various ways,” David says. “But it was just something I wanted to do at that time and see what happened. My dad having passed, and having access to all the information he had put together, mostly in books and clippings, and all the wood and tools, it just seemed like kind of a neat memorial for him.”

David’s dad, by the way, finished that first guitar and had even begun working on his viola da gamba.

“I never really got a clear answer on why he didn’t complete that instrument other than the fact that he was into a million different things on their homestead. And then his health deteriorated and it was never completed. So my memorial to him was going to be to finish that instrument, and then make a violin, maybe for each girl. We were very close, and it was just kind of an extended grieving period and it just felt right to do that. But my wife, who’s very practical, gave me one of her looks and told me to just skip the gamba and go straight to the violin. Because ‘Who knows?’ she said. ‘You might get lucky.’”

So David built a violin.

“It was really remarkable,” he says. “It was kind of like the same experience I had with the guitar but here it was, more than 20 years later, and I had a much better understanding of woodworking but also the kind of energy and passion that the guitar building ignited within me to begin with. I was just really feeling that with this first foray into violin building.”

At the time, Ledah was studying at University of North Carolina Chapel Hill, still using the violin she had won. She had won another competition to be a soloist with the Durham Symphony, and David had just finished his violin. David and Marie traveled to Durham to show it to Ledah, to see if she liked it.

“We went into a big room and she tried it,” he says. “At first she played her other one and then she picked up mine and played it. And we’re just gasping in disbelief at each other because the sound coming out of that violin was un-freaking-believable! Oh, it was just like my heart stopped. And just to see her play so beautifully. It was just immediately evident this was a special-sounding instrument. So she had no hesitation to give the other one back and a week later she was playing my violin as a soloist with the orchestra. It was just a phenomenal way to get introduced to the craft. And truly inspirational for me and just so wonderful on so many levels.”

Of course, having another daughter dedicated to violin playing meant that David had to try his hand at violin making again. He finished his second violin a couple months later.

“Interestingly, Willa’s violin didn’t have the same immediate reception,” David says. “Ledah had no hesitation, she just loved every aspect of it. And I don’t think of Ledah as a capricious person. Willa, she’s a studied person. And, of course, she’s only 15 or 16 at the time. She took it and said, ‘Yeah, I like it. I’ll try it for a couple days.’ And two or three days later, just out of the blue she came to me beaming and says, ‘I love it.’ So that suited her just fine, too. And within that year she also started winning competitions, really significant ones. She had a great run of performances, auditions for these concerto competitions. So it was all the encouragement I needed to drop furniture and dive on in to violin making.”

That was 8 years ago, and violin and viola making is all David has done since.

“I know a lot more now and I’m more confused than ever,” he says, laughing. “It’s such an expansive field and there are so many different ways to do things and the acoustics are this crazy thing and then there’s the finishing and it’s just endlessly absorbing for me.”

And while it’s one thing to please your daughters – even when they’re serious musicians and critics – it’s an entirely different thing for a stranger to plunk down a big chunk of change and walk away with one of your instruments, David says. And yet, that’s exactly what musicians are doing. And they’re thrilled.

The pandemic, as it has for many craftspeople, has put a damper on sales. Folks are no longer coming by David’s shop to try his violins, and direct marketing at schools and with symphony players isn’t happening. So David has gotten creative, offering home trials, sanitizing instruments before shipping them out and giving them rest periods upon their return and before shipping them out again. He’s also donating 10 percent of sales to musicians’ charities for the duration of the pandemic.

Layers of Understanding

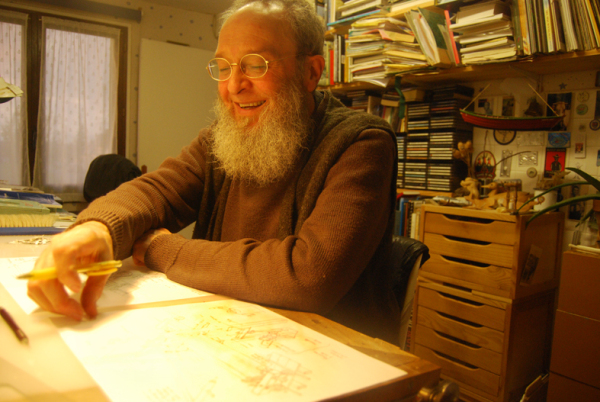

These days David is in his home shop whenever he’s not having dinner with his wife or tending to other chores. The shop is lovely, a basement walk-out with plenty of windows, and a short commute.

“One thing about violin making, there are certain tasks, especially shaping, doing the final carving, shaping the back and top and even the scroll, when it really helps to have a completely darkened shop and then just a single harsh light to really highlight the shadows. And I find, as my eyes are getting older, it’s just harder and harder to see those contrasts that really tell you how good a job you’ve done shaping. So it’s definitely a task I like to do late at night.”

David says probably half the time both he and Marie are working on Saturdays and Sundays. “But, at least in my case, it never really feels like work,” he says. “I just feel so incredibly lucky, incredibly lucky but it’s an obsession I guess, whether it’s magnificent or miserable, I don’t know. But it definitely works for me and just to have something that keeps drawing you in and keeps revealing different layers of understanding. And I feel like I’m just kind of scratching the surface at this point. A lot of the technical stuff I’m pretty comfortable with though violin making is pretty distinctive from other types of woodworking. I’m definitely still picking things up there, kind of putting it all together acoustically. Finishes are a challenge for me.”

David says he was definitely in the right vein as a Krenov-influenced woodworker because the Krenov finishing philosophy is very minimal.

“It’s never been a strong suit of mine so that suited me well,” he says. “But that is definitely not the case when it comes to violin finishing. It can be a very complicated process to end up with something both very beautiful and with the right appearance to it, and also acoustically appropriate to the instrument as well. So there’s a lot of artistic instinct to really pull it off beautifully. And that’s a challenge for me. It’s definitely been an area I’ve put a lot of effort into but still see that I’ve got a long way to go. So if things will allow me to do so, I definitely will continue pushing that area especially hard.”

David talks a lot about luck, and areas he needs to improve.

“I don’t know what it is. I think I just have a feel for wood through long exposure maybe and the guitar influence, but I just had really, really good luck with the acoustic side of the instruments.”

But any outsider looking in would not describe David’s success as the result of luck. Instead, they would point to the hundreds, if not thousands, of hours he has spent in his shop, his dedication – near obsession – with the craft, and an artistic instinct he sometimes claims to not have, but clearly does.

Some proof: Today, Willa, 24, and Ledah, 26, both professional violinists, prefer his violins over any others.

A 2018 graduate of Eastman School of Music, Willa joined the first violin section of the Rochester Philharmonic Orchestra during her junior year in 2017. In addition to playing with RPO, she is the founding member of Copper Hill, a Rochester folk-art band, and in November 2019 she released a solo album called “Ask Me Why” with jazz pianist Sterling Cozza and jazz trumpet player Nathan Kay.

Ledah recently earned her master’s degree in violin performance from The Peabody Conservatory and is currently a member of the Mannes School of Music’s Graduate String Quartet in Residence, Bergamot Quartet, in New York City. She is also a member of the jazz quintet Atlantic Extraction, led by Nick Dunston, and earspace ensemble.

For David, the best compliment is to overhear one of his daughters say, “My dad made it,” when another musician asks about their violin.

Earned Praise

“I’m not an overly confident person, especially in something that has such a grand tradition,” David says. “My goal is simply to make really high-quality instruments for classical players.”

David’s home shop is out in the woods in the mountains of North Carolina – not a lot of high-end players waltz in and out every day. In addition, not having much contact with other makers makes it sometimes difficult for David to figure out where to position himself. But to understand the quality of work, one just needs to listen.

A few years ago, David attended workshops presented by The Violin Society of America at Oberlin College in Oberlin, Ohio. The workshops, quite famous in the violin-making world, David says, serve as a way to get excellent instruction and also “kind of just be with your people.” People come from all over the world to attend. One of the workshops was on acoustics.

“Some makers are interested in that but a lot are not,” he says. “They just kind of go with shop practices that are handed down and end up building fine violins but they don’t necessarily need to know the frequencies that something is vibrating at.”

David brings up a blind study that was done pitting instruments by Stradivari, Guarneri and other famous names against more contemporary ones. The results showed that the contemporary instruments were, actually, slightly favored. The study appeared in a peer-reviewed journal on acoustics and received some flak for its design. So two years later the study was repeated, this time in a more rigorous manner. The results were the same – well-known and talented players and listeners slightly preferred the contemporary instruments.

Back to the workshop: For educational purposes they did double-blind listening tests with musicians and luthiers serving as judges. Players wore dark welding glasses and played behind a screen so the audience couldn’t see what they were playing. In the mix were violins from makers like David, who make a handful a year, and violins from world-famous luthiers.

“There were maybe 30 people in the room and when the violinist played this one opening everybody kind of gasped,” David says. “This was a stand-out sound.”

What David didn’t know was that the violinist was playing his violin.

“I was in a state of shock, as were most of the people there,” he says. “It really was just an incredible shot in the arm. A boost, to say, you’re doing alright.”

David says he doesn’t know why he’s having this luck, thinking maybe it’s a combination of knowing how to work with wood, a long association with it and just really caring about it. Whatever it is, “it’s producing some good results,” he says.

Now 59, David says he never wants to retire. “I just want to do this until I drop over,” he says. Ever since he began woodworking at Krenov’s school, David says he feels like he skipped the work part and just went straight to retirement, spending his life doing what he wants to do with his hours. He thinks back to when he strayed from environmental science, choosing a path of woodworking instead. He credits being able to string woodworking along for all these years in large part, he says, “to my ever-patient and supportive wife. We make a really good team. She understands my motivations having been through that experience herself. So we definitely support each other.”

In the March 2019 issue of Fine Woodworking, David wrote a From the Bench column titled “The Family Violin.” It includes a short video filled with wonderful old photos called “My Father’s Dream.” In the column, David writes: “My personal story is about endings and beginnings, father, son, and daughters, completing one circle and starting another.” And, as David recently discovered reading his grandmother’s memoir, those circles go generations deep and will continue generations on, an interconnectedness much like the beginning and ending of a song.

— Kara Gebhart Uhl