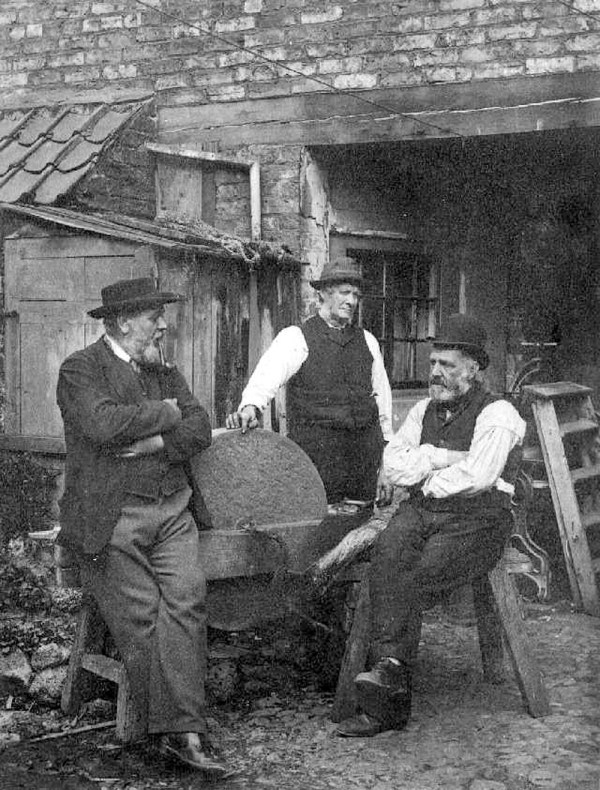

The Thanks of the Society were voted to R. Knight, Esq., for a Collection of Hone-Stones and Grind-Stones, presented by him; together with the following Descriptive Catalogue of them.

Sir, Foster Lane.

In compliance with your request, I have sent, for the Society’s acceptance, a collection of all the principal stones used in the mechanical arts, and of which the following is the catalogue. I have arranged them under two heads, viz. arenaceous and schistose: the few that do not come under either of these heads are separately described, and I shall be happy to give you any further information I am able on the subject.

I am, &c. &c.

Richard Knight.

1. Grit or Sandstone.— Of this variety the universally known and justly celebrated Newcastle grind-stones are formed. It abounds in the coal-districts of Northumberland, Durham, Yorkshire, and Derbyshire; and is selected of different degrees of density and coarseness, best suited to the various manufactures of Sheffield and Birmingham, for grinding and giving a smooth and polished surface to their different wares.

2. Is a similar description of stone, of great excellence. It is of a lighter colour, much finer, and of a very sharp nature, and at the same time not too hard. It is confined to a very small spot, of limited extent and thickness, in the immediate vicinity of Bilston, in Staffordshire, where is lies above the coal, and is now quarried entirely for the purpose of grind-stones.

(more…)

Like this:

Like Loading...