That joiner wrote two short illustrated booklets that explained how to build doors and windows by hand. And what was most unusual about the booklets is that they focused on the basics of construction, from layout to joinery to construction – for both doors and windows.

Plenty of books exist on building windows and doors, but most of them assume you have had a seven-year apprenticeship and don’t need to know the basic skills of the house joiner. Or the doors and windows these books describe are impossibly complex or ornamental.

“Doormaking and Window-Making” starts you off at the beginning, with simple tools and simple assemblies; then it moves you step-by-step into the more complex doors and windows.

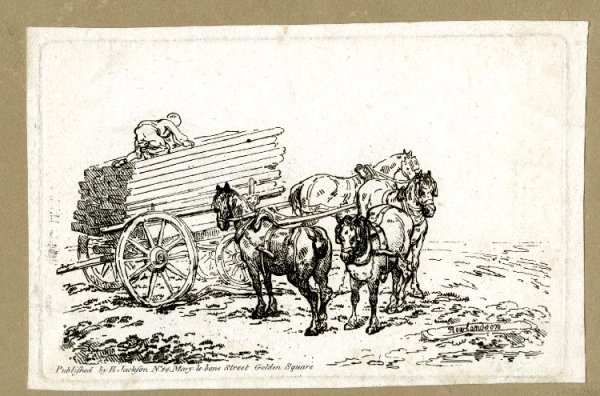

Every step in the layout and construction process is shown with handmade line drawings and clear text. The booklets are written from a voice of authority – someone who has clearly done this for a long time.

During the last 100 years, most of these booklets disappeared. Soft-cover and stapled booklets don’t survive as well as books. And so we were thrilled when we were approached by joiner Richard Arnold in England, who presented us with a copy of each booklet to scan and reproduce for a book.

We have scanned both booklets, cleaned up the illustrations and have combined them into a 176-page book titled “Doormaking and Window-Making.” In addition to the complete text and illustrations from these booklets, we have also included an essay from Arnold on how these rare bits of workshop history came into his hands.

“Doormaking and Window-Making” is a hardbound book measuring 4-1/2” wide x 7-1/4” high. It is casebound, Smythe sewn and features acid-free paper. Like all Lost Art Press books, “Doormaking and Window-Making” is printed and bound entirely in the United States. The cost is $19, and the book is scheduled to ship from Lost Art Press before Christmas. If you order before Dec. 13, domestic shipping is free. After Dec. 13, shipping will be $7.

This title will be available to our small network of retailers in the United States and internationally. If they agree to carry the book, we will announce it here on the blog.

We are proud to be publishing this almost-lost bit of workshop practice. We hope it will inform and inspire you to make your own doors and windows for your shop and home.

— Christopher Schwarz