Earlier this week, contributing editor Suzanne Ellison suggested a short Q&A on early seating furniture, which she has been helping me research for “The Furniture of Necessity.” I consented, as long as the interview was conducted nude. This is my new condition for all interviews, except when it comes to Rosie O’Donnell. The following is the transcript of the chat.

Suzanne: The only condition you have for this email chat was it be done in the nude. Due to the low thermostat setting in my place I asked for a slight change of terms. I will be unclothed but draped (artistically) with a fleece blanket. You agreed this change was fair as you are already covered in fur.

You have written often of your admiration for John Brown and through him you discovered, and became enamored of, Welsh stick chairs. When did you build your first stick chair and how did it turn out? Was this the first chair you made? What did you learn from that first stick chair build?

Chris: I first learned of John Brown in the late 1990s when he was writing columns for Good Woodworking magazine in England. I was completely smitten by his chairs – unlike Windsor chairs, these looked like an animal that would pounce on you.

At the time I’d built quite a number of chairs, but they were all “frame” chairs – built using rectangular mortise-and-tenon joinery. Lots of Morris chairs (too many, really) and other Arts & Crafts arm chairs, settles and cube chairs.

I wanted to go to England to take a class with Brown, but I couldn’t afford the trip, so John Hoffman and I found a chairmaker in rural Cobden, Ontario, who taught Welsh chairs. We went up there for a week, and Dave Fleming introduced us to many of the skills that would change my thinking – turning on a pole lathe, working green stock with a hatchet and froe, all the wacky geometry and (most important) the wedged, conical mortise-and-tenon joint that is the foundation of Windsor chairs and staked furniture.

Suzanne: What, if any, modifications have you made to your stick chairs through the years? Do you have any photos of some of your early stick chairs?

I’ve tried lots of variations – different kinds of arm bows, different spindle shapes, different crest rails. I even tried a couple that had a solid backsplat (those were a design failure and so we sit on those at our house). Mostly, I’ve just been trying to expand the range of chairs that I can build. This book is getting me into three-legged variations and the backstools.

Suzanne: When it comes to necessary furniture it made sense to first have some sort of box or chest to store valuables. Eventually, something to sit on and get off the dirt floor was needed. Can you compare the Countrey Stoole and the staked stool? What are some of the earliest examples of these you have found? (In the van Ostade painting from 1661 the little girl to the left is at a countrey stool, to the left of her is a staked stool or small bench.)

Chris: These forms of furniture are hard to date because they remained unchanged for so long. So the furniture record is murky – stools made in the 1500s look identical to those in the 1800s, so we look to painings and drawings for clues. The Countrey Stool shows up in Randle Holme’s “Academy of Armory,” which I believe is the first written reference to the form. Holme shows it with a thick top and three legs that pierce the top – just like the photo you have.

The van Ostade paintings implies this stool – which could also be a table or work surface – was made from a section of a log that has been crosscut. The end grain is the top. It’s an easy way to make a work surface that can take abuse – the earliest butcher block. Holme’s drawing does not give me the impression that his stool was made from a stump, however.

In contrast, the staked stool or sawbench or whatever, is clearly made from a flat board and the face grain of the board is the working or sitting surface. In the painting, you can also see how some material has been added below the top to create more joinery surface and stiffen the top. This is also pretty typical and is still used today in what we call Moravian stools or chairs – the high form of staked furniture.

Suzanne: You’re not kidding about how long these forms have been around. D-shaped three-legged and rectangular four-legged stools dating to the 10th and 11th century have been found in Britain and Ireland. Since the Vikings left their DNA in large parts of Europe and the Mediterranean, who knows where else this form was used. We don’t know if it was their invention or if it was found on one of their expeditions and adapted for their use.

John Gloag wrote that the two furniture forms are a box and a platform. Despite the 17th-19th century “cheery peasant” paintings complete with dramatic lighting and smiling faces, life and living conditions were pretty grim. How did the stool, a form of platform, improve the life of the peasant?

Chris: Social hierarchy at the time had a lot to do with where you were sitting – hence the word “chairman.” The lowest class sat on the floor. Then you get stools, backstools and forms for the working people – these got you off the floor and in a position to do some work by the fire. The highest class of people got chairs. There’s little doubt that the progression – from floor to armchair – was all about comfort for the human body and was something you earned (or perhaps inherited).

Suzanne: Where actual peasant homes have been preserved, and in paintings, we often see a variety of stools (creepies, D-shaped, square), low benches, backstools and chairs. What does that tell you?

I see a family hierarchy. The stools and benches were multi-purpose – so-called “pig benches” could be used for slaughter and sitting. The chairs were for the heads of the family.

In looking at all these forms in one household you also get the impression that they were user-made. They look like they were made using found materials – sometimes roots, sticks and stumps. And the joinery is basic. You can make a stool with just an auger or brace (which has been around since the 1400s) and a hatchet.

Suzanne: I think it also shows a progression of furniture through the generations of a family. As a new piece was made, or possibly obtained through a dowry, the older stools or benches became available for younger members of a family to use. Subsequent generations had more seating and work surfaces and life was a bit more comfortable. It also speaks to how sturdy these pieces were. They stood up to a lot of use.

You have written about at least three different sawbenches; the most recent is the staked sawbench. What variations have you used in building this sawbench and have you determined your “best build?”

Chris: I’ve been messing around with staked sawbenches to explore the form a bit, inside and out. I’ve been changing the legs, the materials, the way the joint is made and then cutting them apart to see how things work inside the joint. In all likelihood, the original builders didn’t over-think it as much. But I can’t help myself.

The sawbench is the first project in “The Furniture of Necessity,” and it introduces people to the joint and the geometry. Once you build the sawbench, all the other staked forms are a cinch to construct. So I’m trying to start readers off on the right foot – hence the building of the same piece over and over. I don’t know if there is a “best” way to do, but I do have some clues about what makes a good staked joint.

Suzanne: In the last week you have been working on your trademarked Staked Chair, really a backstool. Can you explain the significance of the backstool in the family tree of seating? With the back added how does that change leg angles (rake and splay), if any?

Chris: The geometry of chairs is different than stools. You don’t have to use much rake and splay on a stool because all of the force applied to a stool comes from above – the buttocks. You need just enough of an angle to keep the stool from tipping over, but not so much angle that you trip over the thing constantly.

Adding a back to a stool – a backstool – changes the forces. Suddenly you have lateral forces (your back pressing on the crest and spindles) plus downward pressure.

The historical solution is to keep the front legs minimally raked and splayed like a stool. But you rake the rear feet (or foot) more dramatically backward. Ideally, I like to put the foot of the rear leg under the head of the sitter.

So this form adds comfort and complexity to the construction.

Incidentally, I’m building this three-legged version to test the assertion of furniture historians who say it takes “skill” to sit in a three-legged chair without toppling. That smells of crap.

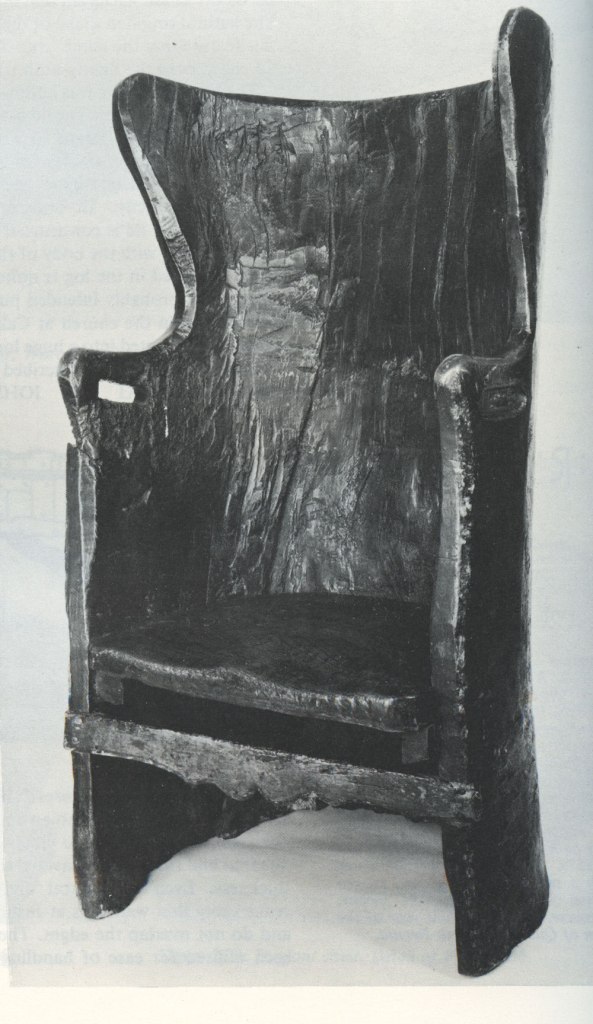

Suzanne: You also have a three-legged stick chair (from one of the Temple Newson Stable Court exhibitions) planned as a future build. This looks to be a transition piece from backstool to chair. You got pretty excited about this little piece when you saw it. What are you looking forward to with this project?

I love Welsh chairs. I don’t think I have a drop of Welsh blood in me, but something about their shape speaks to me. The Cwm Tudu chair (what does that rhyme with?) is particularly enchanting because of its arm bow. It might be made from a found piece of wood with a natural crook. I’m trying to work up the guts to make the chair with a branch for an armbow, but I don’t want it to look like a driftwood sculpture you’d find for sale at Panama City, Fla.

The biggest joy for me is finishing a chair that looks sculptural, sits well and is built using dirt-simple geometry. It’s almost like knowing a secret that has been obscured for many years. And every chair form is a slightly different riddle to solve.

Suzanne: I like the idea of a favored chair as sculpture rather than just a holder of bodies. Experimentation is necessary for the maker to find the balance of design, materials and construction. Mies van der Rohe said, “The chair is a very difficult object. Everyone who has ever tried to make one knows that. There are endless possibilities – the chair has to be light, it has to be strong, it has to be comfortable….”

On the other hand we need to find out how to pronounce “Cwm Tudu.” I can’t use it in a limerick until then.

Last year I sent you an image of a child’s four-legged Welsh stick chair and quickly got a reply from you that the chair had five legs. You were correct, it had five legs. Without being able to examine the chair in person, what do you think was going on with that chair? Three legs too tippy, four still not enough, let’s go with five? Have you come across any other five-legged chairs?

Chris: I can only guess as to why you would make a chair with more than five legs. It uses more material and complicates construction. Here are some guesses, which are probably wrong: Perhaps it started life as a four-legged chair and one leg became loose or weak, so a fifth leg was added as an easier solution to replacing the bum leg. Second theory: It was built for a corpulent person. When dealing with furniture that was made by self-trained woodworkers, non-standard construction methods are the standard.

I have seen folk chairs (and rockers) with many more legs. Chester Cornett was famous for this.

Suzanne: OK, let’s look at the wacky “Sculpstoel” or “Men Shoveling Chairs,” Flemish, by the Circle of Rogier van der Weyden from 1444-50 in the collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. It is earlier than Randle Holme’s history of 17th century seating which you recently posted. What do you see and please give your interpretation of why they are shoveling chairs.

Chris: Once again, I see social hierarchy. This was a drawing for a sculpture for the Brussels town hall. One of the best explanations of its meaning (by Erwin Panofsky) is that the men with shovels are the city fathers creating social order amongst all the classes of people in the city, which are represented by the different kinds of chairs. There are curules and a fancy frame chair that represent the upper classes and staked stools and the like for the lower classes.

As a chairmaker, I see all the forms that were extant at the time. And different construction techniques, from the rectangular mortise-and-tenon on down to the staked stool. What is most important – in terms of the “Furniture of Necessity” – is that these 15th-century forms are indistinguishable from Holme’s 17th-century forms or the extant 19th-century forms in Wales.

— Christopher Schwarz & Suzanne Ellison

Like this:

Like Loading...