This is an excerpt from “The Joiner and Cabinet Maker” by Anon, Christopher Schwarz and Joel Moskowitz.

The two-foot rule was the standard measuring device for woodworking for hundreds of years. The steel tape was likely invented in the 19th century. Its invention is sometimes credited to Alvin J. Fellows of New Haven, Conn., who patented his device in 1868, though the patent states that several kinds of tape measures were already on the market.

Tape measures didn’t become ubiquitous, however, until the 1930s or so. The tool production of Stanley Works points this out nicely. The company had made folding rules almost since the company’s inception in 1843. The company’s production of tape measures appears to have cranked up in the late 1920s, according to John Walter’s book “Stanley Tools” (Tool Merchant).

The disadvantage of steel tapes is also their prime advantage: They are flexible. So they sag and can be wildly inaccurate thanks to the sliding tab at the end, which is easily bent out of calibration.

What’s worse, steel tapes don’t lay flat on your work. They curl across their width enough to function a bit like a gutter. So you’re always pressing the tape flat to the work to make an accurate mark.

Folding two-foot rules are ideal for most cabinet-scale work. They are stiff. They lay flat. They fold up to take up little space. When you place them on edge on your work you can make an accurate mark.

They do have disadvantages. You have to switch to a different tool after you get to lengths that exceed 24″, which is a common occurrence in woodworking. Or you have to switch techniques. When I lay out joinery on a 30″-long leg with a 24″-long rule I’ll tick off most of the dimensions by aligning the rule to the top of the leg. Then – if I have to – I’ll shift the rule to the bottom of the leg and align off that. This technique allows me to work with stock 48″ long – which covers about 95 percent of the work.

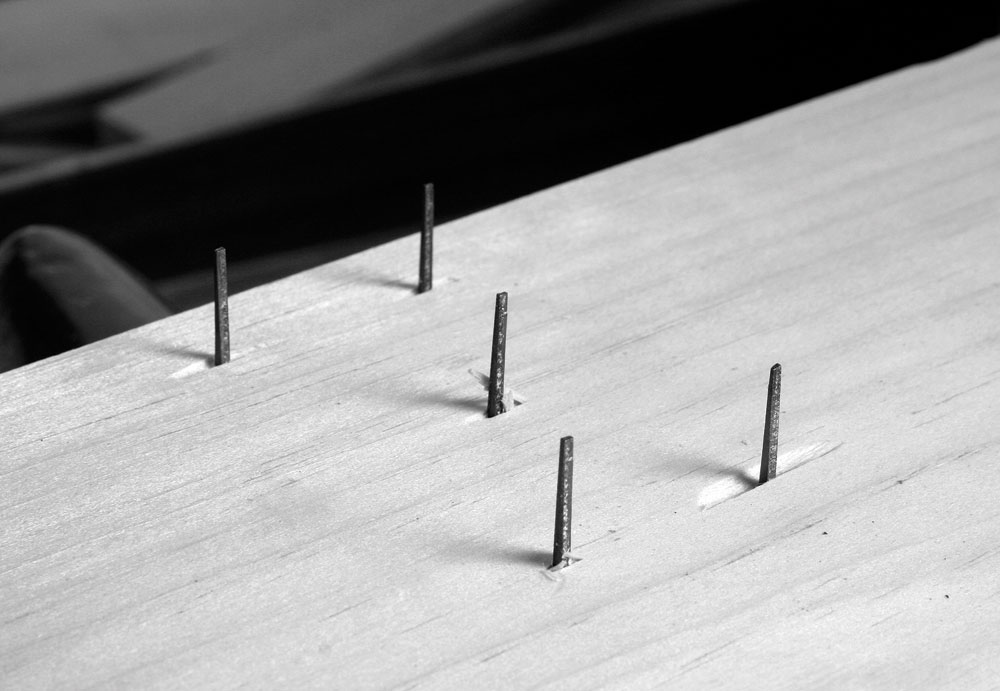

Other disadvantages: The good folding rules are vintage and typically need some restoration. When I fixed up my grandfather’s folding rule, two of the rule’s three joints were loose – they flopped around like when my youngest sister broke her arm. To fix this, I put the rule on my shop’s concrete floor and tapped the pins in the ruler’s hinges using a nail set and a hammer. About six taps peened the steel pins a bit, spreading them out to tighten up the hinge.

Another problem with vintage folding rules is that the scales have become grimy or dark after years of use. You can clean the rules with a lanolin-based cleaner such as Boraxo. This helps. Or you can go whole hog and lighten the boxwood using oxalic acid (a mild acidic solution sold as “wood bleach” at every hardware store).

Vintage folding rules are so common that there is no reason to purchase a bad one. Look for a folding rule where the wooden scales are entirely bound in brass. These, I have found, are less likely to have warped. A common version of this vintage rule is the Stanley No. 62, which shows up on eBay just about every day and typically sells for $20 or less.

The folding rule was Thomas’s first tool purchase as soon as Mr. Jackson started paying him. I think that says a lot about how important these tools were to hand work.

— MB