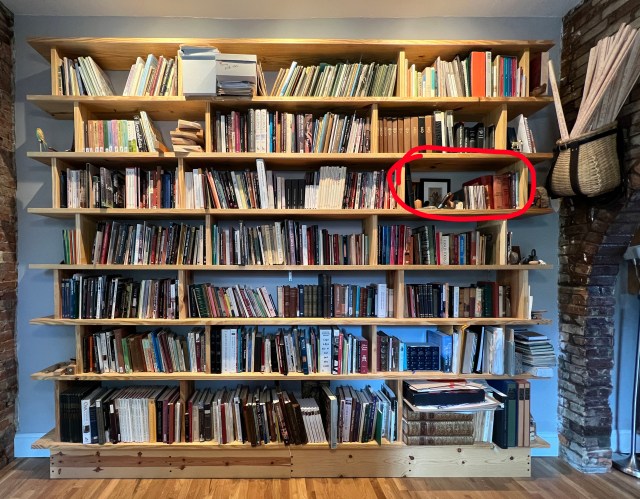

Often when we start working on a new book, among the first steps are to acquire any good (and sometimes bad) research that’s already been done on the subject – at least for topics that haven’t been written about ad nauseam (see workbenches…or Shaker furniture; we’d need far more shelving to hold everything written on those subjects).

This bookshelf bay holds just about everything Chris could find that’s been written on campaign furniture, from books – OK, book – to various magazine articles and (most helpful) the catalogs from Christopher Clarke Antiques. Also, period sales catalogues for British Empire posting needs.

It also holds some “overflow” and backup tools.

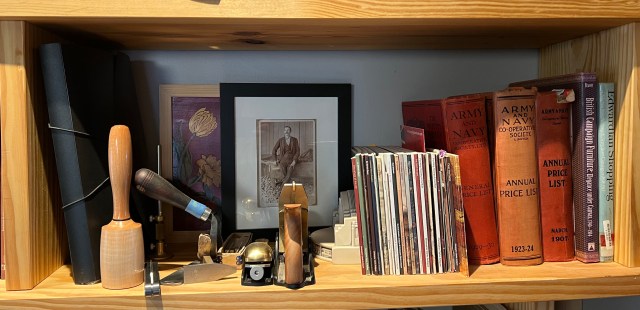

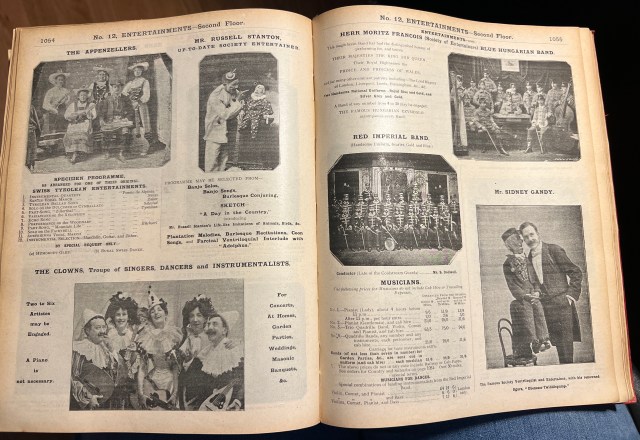

Let’s start with the Army & Navy Co-operative Society price lists. These listed just about everything the British military man could need or want for his self, family or house – whether posted to a colony or not. Find what you needed, then go to one of the stores, or have it delivered (sometimes free of charge), from London to Kolkata (formerly known as Calcutta). Chris bought three of the price lists, because in addition to a vast selection of pie frills, corsets and party performers (see below), you could purchase campaign (and other) furniture. In our collection are the price lists from March 15, 1907, 1923-24 and 1929-30. These are fascinating – and you can now find most of them digitized online (you could not in 2014, when “Campaign Furniture” was published). But that does take away the fun of paging through them from the comfort of my Rhoorkhee chair (I could lose whole days in these).

The colorful paperback books to the left of the Price Lists are every print catalog that Chris could get his hands on (and in the black binder to the far left are printout of the digitized ones that weren’t available in print) from Christopher Clarke Antiques Ltd., an incredible store in the Cotswolds of England – and the only place that specializes (specialises?) in British military campaign furniture and travel-related antiques. The Clarke brothers, Sean and Simon, kindly answered all the questions Chris had that no one else could, and they proofread “Campaign Furniture” for us. Their shop is half store, half research library. They have every photo of every piece they’ve ever acquired and sold, along with notes about it and its history. They’re under contract for a book with Lost Art Press – and we eagerly await their having time to write it. In the meantime, follow their Instagram feed for close-up looks at some fascinating pieces.

Tucked alongside the Christopher Clarke catalogues is “Britain’s Portable Empire: Campaign Furniture of the Georgian, Victorian, and Edwardian Periods,” a 2001 museum exhibition catalogue from The Katonah Museum of Art in New York.

On the far right are “Edwardian Shopping: A Selection from the Army & Navy Stores Catalogies 1898-1913” compiled by R.H, Langbridge (David & Charles, 1975) and “Britsh Campaign Furniture: Elegance Under Canvas, 1740-1914,” by Nicholas Brawer (Abrams, 2001), the earliest book we know of on the subject. (Brawer was also the curator for the museum exhibition mentioned above.)

The aforementioned black binder also holds copies of various antiques magazines that featured articles on select pieces of campaign furniture, and the working layout of the first draft of “Campaign Furniture.”

Now the tools: These are a mix of tools that are backups in case Chris’s primary versions get lost/destroyed/etc. (the Lie-Nielsen No. 3, a Lie-Nielsen 60-1/2 block plane, an extra block plane blade, a Blue Spruce 16 ou. mallet*, a Lucian Avery scorp and a Tite-Mark cutting gauge), and overflow tools – things he now longer uses…mostly because we now have versions of them from Crucible Tool (the Sterling Tool Works dovetail marker and two small Vesper Tools sliding bevels ). Also stored there is the first of the Crucible Tools Sliding Bevel that worked like it was supposed to (a lot of R&D went into making the two locking mechanisms perfect).

The sepia photo is a period original that shows a nattily dressed man leaning against an English-style bench; he’s holding a pair of dividers. So of course we had to have it. The marquetry panel is a thank-you gift from a Kickstarter campaign to which Chris donated.

The bookend (which shows one of Cincinnati’s Art Deco gems, Union Terminal) is from Rookwood Pottery.

– Fitz

*That Blue Spruce mallet is brand new. When I was leaving to teach in Florida last month, I grabbed the older backup one and tossed it in my carry-on. I was assured by my shopmate and a visitor that I would have no trouble with it at TSA – they’d taken one through security many times. They were wrong. So I bought us a new backup as I awaited boarding. (Thank goodness I didn’t try to take my beloved and irreplaceable blue Blue Spruce mallet!)

p.s. This is the fifth post in the Covington Mechanical Library tour. To see the earlier ones, click on “Categories” on the right rail, and drop down to “Mechanical Library.” Or click here.