An addreſs to the public.

That the preſent era bids fair to finiſh the human character, in this our happy hemiſphere, muſt be evident from an enumeration of ſome late diſcoveries. In Maſſachuſetts, an unlettered mariner has hit upon the art of ſeparating freſh-water from ſalt water, without the inſtrumentality of heat! In Connecticut, a tallow chandler has laid open the ſecret of uniting water with tallow, a diſcovery of no ſmall importance to mankind; inaſmuch as it muſt render light cheap, by lowering the price of candles!

In Pennſylvania, a ſociety of ſages, aſſiſted by the legiſlature of the ſtate, have found out a method of improving philoſophy by means of digging of cellars, and keeping rooms to let. It is likewise notorious, that certain alchymiſts, in the pay of New-Hampſhire and South-Carolina, have inſtructed the people of thoſe republics in the myſtery of converting old houſhold furniture or barren land into bona fide gold or ſilver.

This alludes to the laws making property a tender in payment of debts.

Inſpired by ſuch examples, it is not to be preſumed that ſo reſpectable a ſtate as Maryland will doſe away the bright morning of peace, without a ſingle atempt at diſcovery, beyond a town-clock, which, perhaps, may never ſtrike, or a foundered corporation, which may never recover the uſe of its limbs. Surely it is time for an independent people to leave the path trodden by their ſhackled anceſtors, and aſtoniſh the world by ſome new and extraordinary effort of genius!

Now is the fortunate moment when habit is to give place to imitation: when stronger inducements have ariſen, to call upon every lover of his country to unite in providing againſt an evil, which philoſophy ſees approaching with rapid ſtrides.

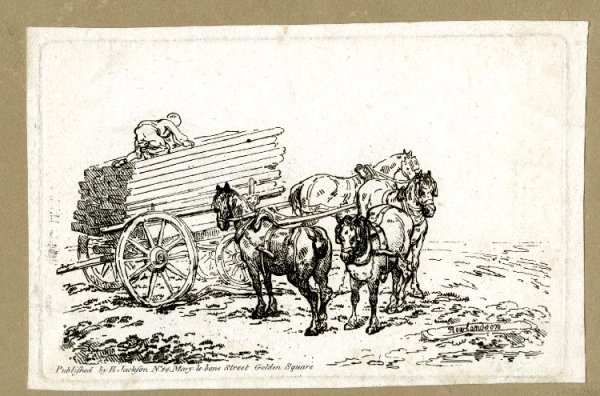

—I mean, my fellow citizens, a direful ſcarcity of plank and ſcantling even in this timber-ſtate and its extensive territory.

If it ſhould be objected that Maryland is a limited ſtate, and does not, like Virginia, poſſeſs extenſive uncultivated territory, the objection offers one of the moſt cogent reaſons for making the moſt of what we have.

Heretofore, it is true that the political economiſts have widely differenced reſpecting the ſuperiority between deal boards and pine trees. In this point, however, they all agree, that there must have been pine trees, before they could be cut into deal boards.

Here it would ſeem as if the author had read every writer in political economy, as they quaintly ſtyled; his modeſty however, leads him to confeſs that he is not ſure that he has read any one of them. In this inſtance, he has followed the practice of great writers, who make a parade of their reading.

Taking this ſurprising diſcovery of the economiſts for a guiding maxim, it is humbly propoſed, that the carpenters, the joiners, the ſawyers, and all the workers in wood, do forthwith commune together, and form themſelves into a ſociety for inventing the easiest and cheapest method of melting down ſawduſt and chips, and caſting them into deal-boards, without cracks or knots.

The writer’s candor compels him to acknowledge that he has taken the hint of this ſociety from a London news-paper, printed in the year 1720.

I am aware that this undertaking is ſubject to be conſidered as expenſive without being profitble: and that it may alſo be ſaid of it, that the great labour required to make deal boards after this faſhion will prove an inſurmountable obſtacle to ſucceſs. I truſt, however, that ſuch objections can be eaſily obviated, and that a people ſufficiently liberal, will not condemn what is propoſed, merely because it is new!!!

Thomas Coliflower.

Baltimore, April 3, 1786.

The American Museum or Repository of Ancient and Modern Fugitive Pieces,

Prose and Poetical. Vol II – 1787

—Jeff Burks