If you read this blog, you probably are are interested in hand tools. And if you are at the beginning of your journey, this blog entry is for you.

If you read this blog, you probably are are interested in hand tools. And if you are at the beginning of your journey, this blog entry is for you.

Popular Woodworking Magazine commissioned me to make a series of 10 to-the-point videos about hand tools that try to strip away the confusion so you can get to work with a basic set of hand tools and a minimum amount of agony.

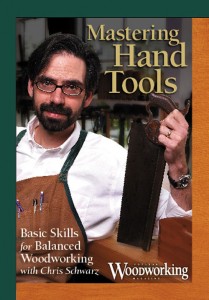

The series is called “Mastering Hand Tools: Basic Skills for Balanced Woodworking,” and it will be available both on DVD through ShopWoodworking.com and through ShopClass on Demand, the magazine’s streaming video service.

The DVD version is on sale right now before it is released on April 16. You can save $5 by clicking here. You’ll pay only $19.99.

If you want to watch the videos now, you can get a subscription to Shop Class on Demand. If you act today (Sunday, April 1), you’ll get a half-price deal that gives you six months of unlimited access to all the videos on ShopClass (and there are a lot of good ones) for $24.99. Click here to read up on the details. They also offer a free trial subscription if you aren’t ready to commit.

They’ve posted a couple of the segments from this “Mastering Hand Tools” series on ShopClass so far and I am told a new video will appear every other week until all 10 segments are up.

I am quite pleased with how this series came out. Though I really dislike being on camera, the crew put me at ease and the videos have a casual feel like being in a one-on-one class – but they are all concise so you get what you need without a lot of blather.

So what are all the segments about? Here’s a list of what we filmed.

1. Why Learn Hand Tools? While some of this might seem obvious to those who already use them, the benefits of mastering hand tools for a power tool woodworker are sometimes surprising. They can be more accurate and faster than power tool equipment.

2. Knives, Marking Gauges and Cutting Gauges: The most important hand tool isn’t the saw, plane or chisel. It’s the marking knife or cutting gauge. These are the tools that guide your saw, chisels and planes. If you can mark a clear line with these tools, you will find it easy to work down to those lines.

Picking the right marking tool can be daunting. What are the differences between a marking gauge and a cutting gauge? What’s a panel gauge? Do you really need a mortise gauge?

And when it comes to marking knives, most woodworkers get quite confused. Do you need a single-bevel knife? A double-bevel? A spear-point knife? How thick? How long? The choices can be overwhelming.

In this video, we explain what is important when it comes to marking tools. We show you how to adjust any tool so it makes the kind of line that hand tools need. It’s not hard – you just need to think like a saw, plane or chisel.

3. Handsaws: Where to Start, How to Saw and How to Become a Maestro: No matter how much you love your table saw, there are times that it is neither the safe nor smart option. For example: Knocking down rough stock in a parking lot, cutting short stock to length or cutting fine dovetails.

However, if you are smart, you can get into handsaws with only two inexpensive saws that will never need sharpening and will fool your friends at Colonial WIlliamsburg into thinking you are a handsaw maestro. The trick is to pick the right (cheap) saws and know the insider tricks.

This video will show you how to do lots of work with an inexpensive dozuki and Sharpoint saw. You’ll learn the 10 mistakes that most sawyers make and how to track a line every time (it doesn’t take years of practice). Once you have mastered these two saws, we’ll explore the traditional kit of five saws (two handsaws and three backsaws) and what these five saws can do for you if you decide to go deeper into the topic.

4. Chisels: Basic Sharpening, Paring and Chopping & Mallets: Sharp chisels make woodworking easier. They square out routed corners, they chop out waste and they can pare plugs flush with your work. But modern sets of chisels can cost as much as $250. Then you have to buy the sharpening stones (another $200) and learn how to sharpen.

What if we could show you how to take two home center chisels, some sandpaper from your shop and a $10 jig and be set for life? It’s true. You don’t have to get a PhD in metallurgy or sell a kidney to have the sharpest chisels in the city.

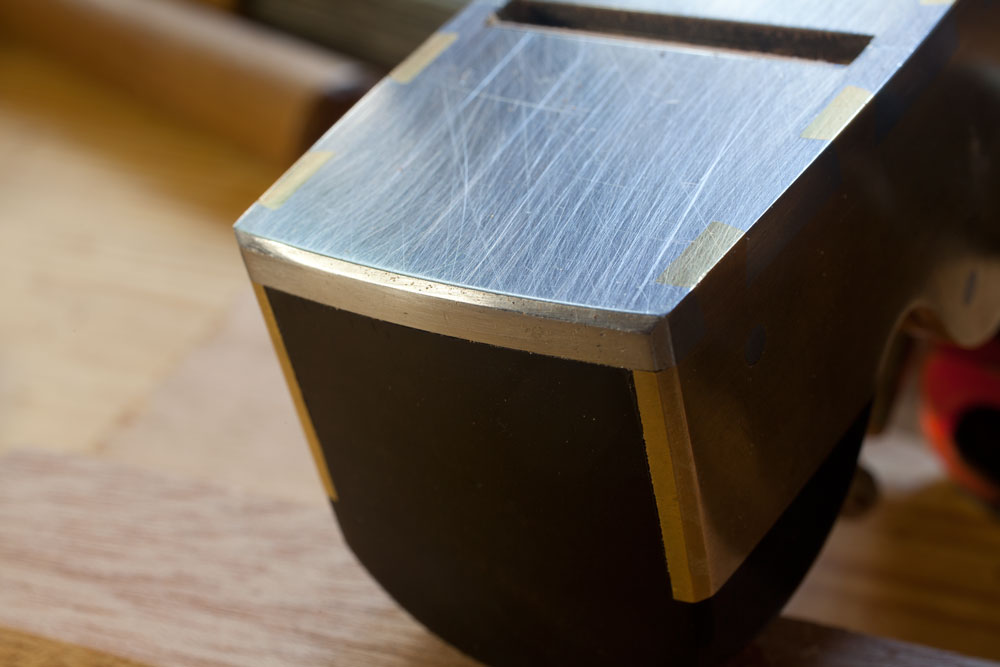

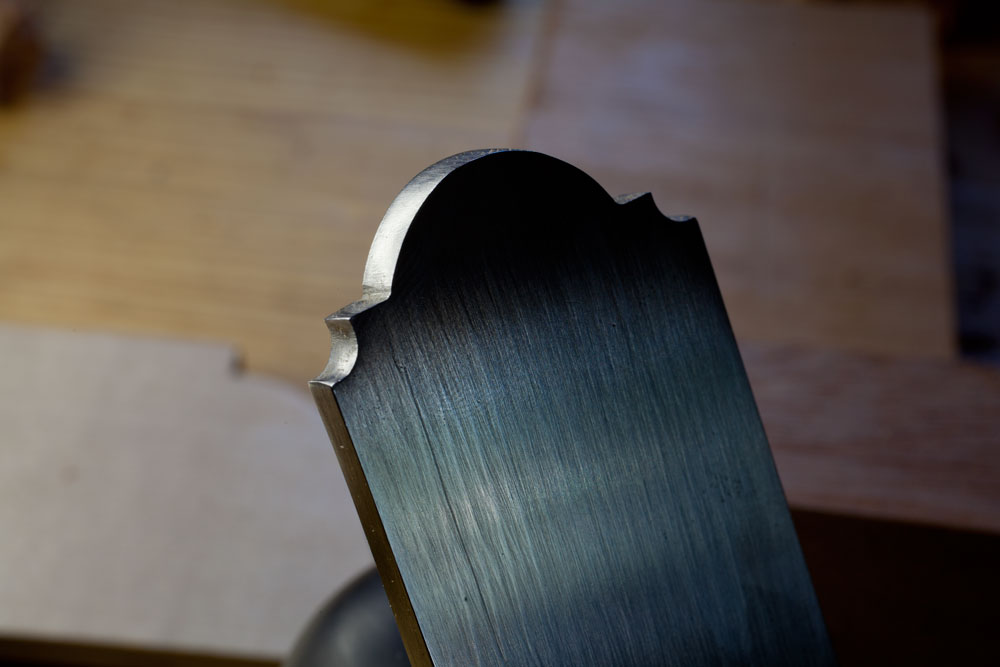

Once you have these two chisel sharp, we’ll show you the right way to chop and pare with these tools – chisels are the most dangerous hand tool, period. You’ll also learn about the most important tools that work with your chisels: the mallet. Learn the differences between the round- and square-headed varieties and what weight you should choose for your work.

5. Rasps: Shaping Curves and Cabrioles: Cabriole legs look intimidating, and sculptural forms (think Maloof rocker) look impossible if you are a fan of plunge routers instead of rasps. But the truth of the matter is that you don’t need a whole tool roll of rasps and carving tools to make shapely curves.

Instead, you just need one inexpensive tool – that never needs to be sharpened – and know the basic strokes to turn out cabriole legs and compound shapes with ease. Once you master this Shinto rasp, we’ll explore the traditional rasp kit of the hand-tool woodworker, including cabinet rasps, modelling rasps and rattails.

We’ll look at the difference between machine-made and handmade rasps and why it is usually worth the extra money to buy the better tool.

6. Card Scrapers & Scraper Planes: No matter how awesome your planer and jointer are, there are going to be small areas of torn grain that will resist your every effort to remove them. Card scrapers are the secret weapon in the war against tear-out. The problem is that sharpening them seems to require a lifetime of experience or some crazy jig.

We show you how to sharpen this essential tool with a file, a block of wood, some sandpaper and a burnisher. You’ll be making wispy shavings and tear-out-free surfaces in one afternoon. Plus you will learn how to prevent your thumbs from burning using a trick from your refridgerator (seriously).

Once you can sharpen a card scraper, you also can apply that knowledge to a cabinet scraper, which is an inexpensive and highly effective scraper plane. We’ll show the basics of using this tool, which can save your thumbs if you have a lot of scraping to do.

7. Braces and Hand Drills: The Ultimate Cordless Drills: No matter how big your cordless drill is, there are some wide or deep holes that will cook your drill. That’s why we think every woodworker should own an inexpensive brace, which allows you to make huge and deep holes with little effort – once you understand how to sharpen the bits with a common file.

You don’t have to spend a lot of money, either. We show you how to pick a garage sale special for $5 and pick bits from the 25-cent bin. You will be amazed at what a brace can do once you have a sharp bit.

Once you have a brace, which powers bits from 1/4” and up, you’ll want to learn to use a hand drill, which drives the smaller bits. Used hand drills, which are sometimes called “eggbeater” drills, are available almost everywhere and are safe and fun to use.

8. Jack Planes: The Widest Jointer Ever: If you have a 6” or 8” jointer you know the heartbreak of buying 14”-wide rough boards. What do you do to get the boards flat? Ripping the lumber into narrow widths is almost a crime.

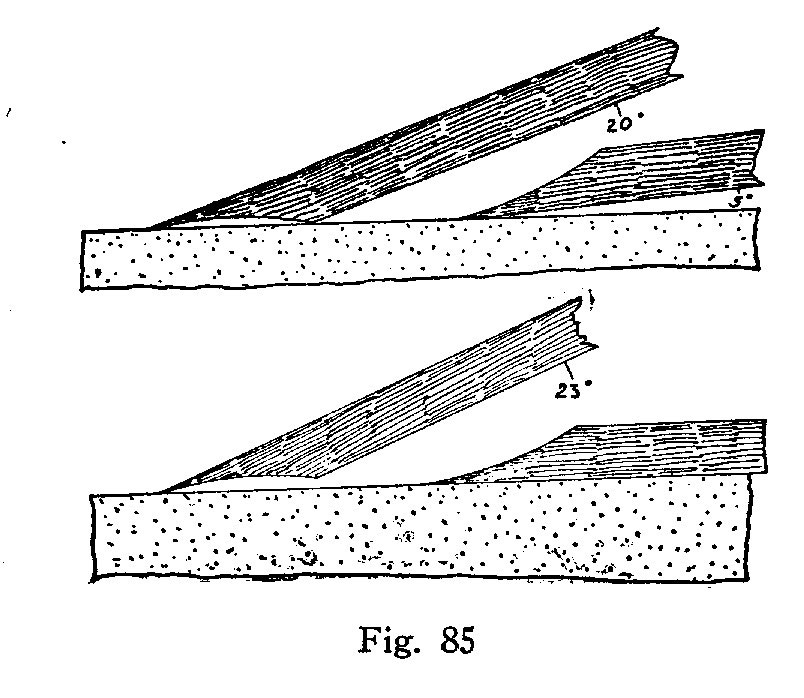

You need to learn how to set up and use a jack plane. With a properly set up jack you can surface the face of almost any rough board in 15 minutes (and not be out of breath!) so it can go through your powered planer. The trick is learning how to shape the plane’s cutter and how to use the tool in a way that exploits the weakness of the tree.

We’ll cover grinding the iron, honing the iron and using the jack plane in ways you probably never imagined. It can reduce boards in width with shocking speed. It can also add texture to your projects, which is a nice detail if you build reproductions.

9. Router Planes: The Power-tool Woodworker’s Friend: Router planes are excellent at cleaning up machine-made joinery. They flatten the bottoms of dados, adjust rabbets and can even cut hinge mortises so you don’t have to balance a huge router on the edge of cabinet.

Router planes are easy to set up, sharpen and use – even if you’ve never used one before. We show you the trick to sharpening the L-shaped cutter – it’s easier than you think. We then show you how to make the tool do things that most machines cannot, such as getting a perfectly sized tenon on a rail that is in the absolute center of the work.

10. Smoothing Planes: Stop Sanding! Few woodworkers like power sanding. You can reduce (or almost eliminate) your sanding chores by learning to sharpen and set a handplane. This will turn one of the dreariest parts of a project – sanding – into one of the most enjoyable – planing.

We’ll start with a block plane. One of its most amazing feats is that they can save you from sanding the narrow edges of your projects forever. With one or two swipes, you can produce a perfect, ready-to finish surface.

We show you how to set up a block plane using sharpening materials you probably already have on hand. And we show you a trick to setting them up that hand-tool afficianados have been guarding for centuries.

Again, the DVD is on sale now until the release date. Click here for information or to order it from ShopWoodworking. Or if you want to start right now, go to ShopClass on Demand.

— Christopher Schwarz

Like this:

Like Loading...