This is an excerpt from “The Woodworker: The Charles H. Hayward Years: Volume III” published by Lost Art Press.

This type of dovetail sometimes creates a difficulty because of the length of the joint. It is, of course, essential that it grips throughout its length, and the usual fault is to make it tight in some parts and slack in others. The practical process is dealt with here.

In its simplest form this joint consists of a plain groove with either one or both sides at the usual dovetail angle cut right across the wood, and a joining piece cut dovetail fashion to fit, as in Fig. 1. It is a thoroughly strong joint and is satisfactory for many jobs, but suffers from two disadvantages. One is that the dovetail necessarily shows at the front edge; the other is that, since the one piece has to slide right in from the edge, it is awkward to make a joint that is tight enough to be strong, yet free enough to slide across. The wider the joint the more awkward it is.

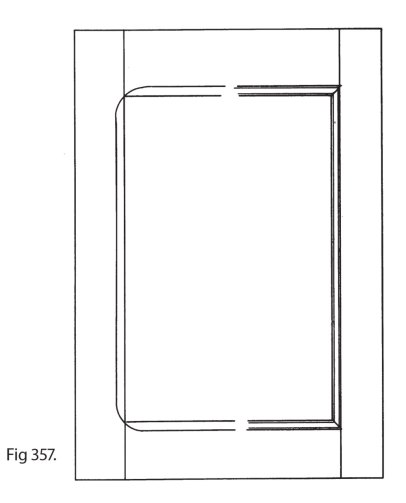

Tapered Dovetail. To overcome these drawbacks the stopped and tapered dovetailed housing shown in Fig. 2 was introduced. It is extremely handy for carcase work, and forms a strong fixing for shelves and similar parts. Its special use is in tall structures in which the ends might be inclined to bow outwards. The dovetail effectually prevents this, yet it is entirely concealed by the stop. Note that the top cut (which is cut in square) is at 90 deg., whilst the taper is formed beneath. The dovetail is formed on this sloping cut. It will be realised that it is really a bare-faced dovetail and that the bare face is at the top. In this way the shelf is bound to be square.

When marking out the joint, square across the sides the over-all thickness of the shelf, cutting in the top line with the chisel and the lower one in pencil. Then mark in the tapering line with the chisel. The depth of the stop can be marked with the gauge (keep the gauge set so that the shelf can be marked with the same setting.)

Cutting the Groove. The sides of the groove have to be sawn in, and many workers find a difficulty in using the saw because this cannot be taken right through. There is no difficulty, however, if a recess is cut up against the stop as shown inset in Fig. 3. Chop it with the chisel to the same depth as the groove and work the saw with short strokes, allowing the end to run out in the recess. One side of the latter must be at the dovetail angle, of course.

To form a strong joint it is clear that the saw cut on the dovetail side must be at the true angle and that it must agree with that of the shelf. Fig. 4 shows how this can be assured. A piece of wood is cut off at one end at the required angle, 78 deg., and is held down on the wood with a cramp or screw and the saw held against the end as shown. Before fixing it, however, it is generally advisable to make a few strokes with the saw upright. This saves any tendency for it to slip owing to the angle. In any case the usual practice of chiselling out a small sloping groove is advisable (see inset in Fig. 4).

The preliminary removal of the waste is done with the chisel, this being followed by the router. If this is held askew it will generally be found that the cutter will reach right under the dovetail slope—unless it has an extra high pitch, in which case the chisel will have to be used to reach beneath.

The Dovetail. In the case of the dovetail on the shelf the simplest plan is to gauge in the depth and cut a square rebate with the saw and rebate plane. Form the taper (also with the plane) and then cut in the dovetail angle with the chisel. It will be realised that the preliminary saw cut is deep enough to reach to the dovetail depth. If the work is done with the wood cramped down on the bench, a spare piece of wood with the end at the correct angle can be used as a guide, as in Fig. 5. Adjusting the wood away from or towards the work will enable the chisel to take up the true angle. In any case, it is intended purely as a guide. The advantage of the joint will become obvious when it is fitted, because it is loose until driven right home when it at once becomes a tight fit throughout its length. It should make a close fit, but over-tightness should be avoided as this tends to force the ends out of truth.

— MB