Peter Follansbee’s fantastic and sprawling tome on early American woodworking is now available for pre-publication ordering here. The book is $49 and will ship in May. Customers who order before the publication’s release date will receive a free pdf of the book at checkout.

“Joiner’s Work” took eight years for Peter to complete, and it shows. Not only does it cover a lot of haircuts and wardrobe changes in his step photos, it also covers an enormous swath of Peter’s work. For the last eight years, Peter has been documenting his work at the bench and the many variations and iterations of the typical pieces from a 17th-century joinery shop.

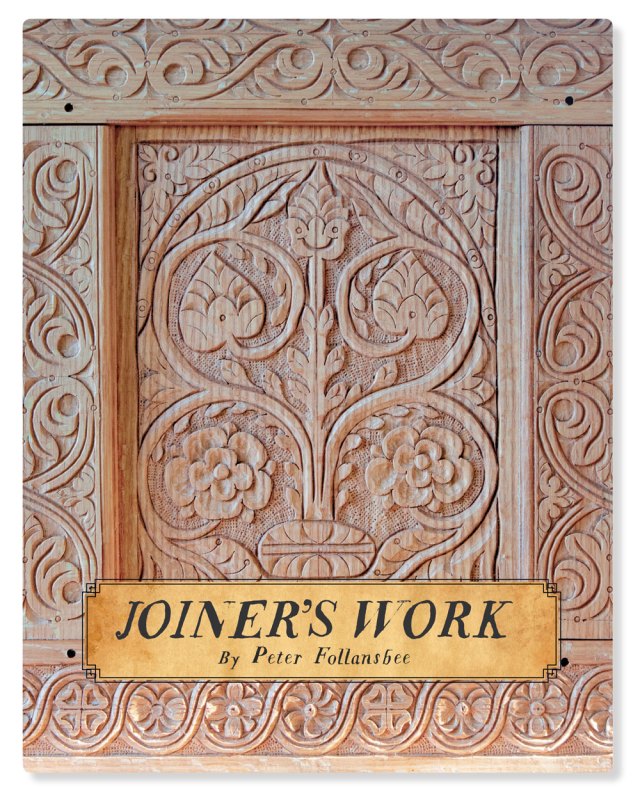

As a result, Peter illustrates not just one joined chest, but more than a dozen variations, all with different carving patterns, slight joinery variations and different arrangements of rails, muntins and panels. It is a visual feast and I spent many hours just digesting the carved panels.

If you’re new to 17th-century furniture, here’s what you need to know: It’s neither dark nor boring. Instead, it’s a riot of geometric carvings and bright colors – all built upon simple constructions that use rabbets, nails and mortise-and-tenon joints. Even if you don’t fancy yourself a period furniture maker, there is a lot in here to learn.

If you like green woodworking, “Joiner’s Work” is doctoral thesis on processing furniture-shaped chunks of lumber from the tree using and axe, froe, hatchet and brake. If you are into carving, Peter dives into deep detail on how he festoons his pieces with carvings that appear complex but are remarkably straightforward. And if you love casework, “Joiner’s Work” is a lesson on the topic that you won’t find in many places. Peter’s approach to the work, which is based on examining original pieces and endless shop experimentation, is a liberating and honest foil to the world of micrometers and precision routing.

The book features six projects, starting with a simple box with a hinged lid. Peter then shows how to add a drawer to the box, then a slanted lid for writing. He then plunges into the world of joined chests and their many variations, including those with a paneled lid and those with drawers below. And he finishes up with a fantastic little bookstand.

Construction of these projects is covered in exquisite detail in both the text and hundreds of step photos. Peter assumes you know almost nothing of 17th-century joinery, and so he walks you through the joints and carving as if it were your first day on the job. Plus he offers ideas for historical finishes.

What Peter doesn’t provide, however, is detailed construction drawings of each piece with a cutting list and list of supplies you might need. As you quickly learn in the opening chapters, the size of the projects (and their components) are based on what you can harvest from the tree.

There’s immense flexibility in this method of work. But to help keep you oriented, Peter provides pencil sketches (made by the wonderful Dave Fisher) that explain the anatomy of each project, plus rough sizes that will help you plan out your work in the woods and at the workbench.

If you are accustomed to CAD renderings, this will feel unfamiliar. But if you are brave, I think you’ll find it a freeing way to build these pieces (which frankly look weird when built using contemporary precision techniques).

Throughout the book you’ll have the voice of Follansbee to guide you. If you’ve ever heard him speak, you will instantly recognize the rhythm of the language and the dry humor. We took great pains to retain Peter’s voice in this book (I think we succeeded).

“Joiner’s Work” is a massive tome, coming in at 264 pages in an 8-1/2″ x 11″ format. The text and full-color images are printed on coated #80 paper. The pages are bound to create a permanent book. We sew the signatures then glue and tape the spine with fibrous tape. The pages are then wrapped by heavy hardbound covers that are covered in cotton cloth. The whole package is wrapped in a #100 dust jacket that is coated with a supermatte laminate to resist tearing and long-term wear.

And, of course, all of this is done in the United States.

Order your copy here.

— Christopher Schwarz