It was a cold February day, windy and damp, like you get in the season in the Touraine region of France. I had spent a couple of hours wandering among the craft masterpieces in the Musée du Compagnonnage (the Guild Museum) in Tours, France, near where I live. There was everything from micron-accurate models of impossibly complex wooden roof structures built by guild carpenters to castles built by bakers in meringue.

I am a booky kind of guy, and was spoiled for choice among the beautiful books in the museum shop when I stumbled across “Dans lʼAtelier de Pépère” (Grandpaʼs Workshop) A hand-tool woodworker, learning whatever I could about the history of woodworking, and woodworking in France, the cover had me hooked from the moment I picked up the book.

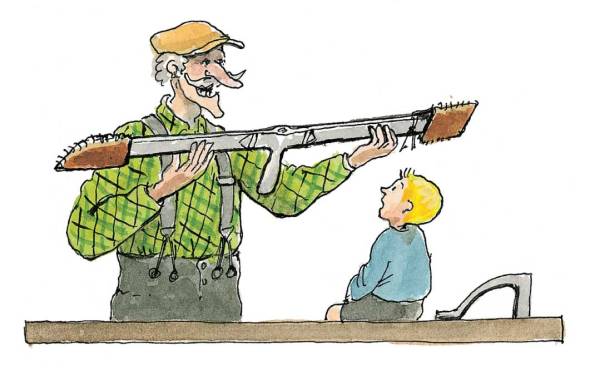

There was the besaigue, the emblematic tool of a house carpenter here, combining a slick and a beefy mortise chisel at each end of a steel shaft, a boy sitting on a Roubo-style bench, (chisel rack, no tool tray) next to a hand-forged holdfast, listening to his grandfather. There was a wooden jointer plane, a saw set and file next to an early handsaw with a London- style tote, a French-style miter square, and even a carpenter fighting a dragon with a broad axe. What more could a woodworker and hand-tool geek with kids ask for?

It is a graphic novel, the story of a boy, Sylvain, who spends his vacations at his grandparentsʼ place in the French countryside. His Grandpa is a joiner, old school, and the boy builds little houses and boats with the scraps and nails he is given. But the story is mostly the tales that Grandpa tells the boy about his tools and his ancestors, as Sylvain is the youngest of a family of woodworkers – joiners, carpenters, wheelwrights, turners, chairmakers, coopers, clog makers – a family that has spent centuries picking wood chips out of their wool sweaters and brushing the sawdust off their shoes.

At the time I had never heard of Maurice Pommier, the author and illustrator. But it was clear that he was one of the clan, a guy I would really like to meet. The story was wonderful, but the illustrations were a revelation. I had spent years, and tracked down many books to learn about traditional woodworking and how it was done in France. The drawings were elaborate, done in a warm almost childlike style, but it was all there, there was not one wasted line. And the more I looked, the more I saw. In an illustration of a carpenterʼs shop there were dancing elves, but also a big band saw like I had seen at a sawmill near my in-lawʼs place and in the shop of a boatbuilder who specializes in big traditional river boats. In the same drawing, way back in the shadows, models of roof carpentry, just like I had seen minutes before at the Guild Museum.

Not one false note, not that I could hear, anyway.

My girls like the book, as much as to see that their father was not alone in his mania, I suspect, as for the story itself. But I was again struck by the wealth of details, and the history depicted. So I took time to read “Grandpaʼs Woodshop” through, again, alone in the quiet of the evening. In it there were two Anarchistʼs tool chests, and their tool kits, a chairmaker turning chair posts green on a pole lathe under a lean-to, an American carpenter traveling the countryside building whatever people need, the king of the dwarves forging a tool for the carpenter who killed the dragon. There were the names of all the traditional tools I had seen while rummaging through the tables in the flea markets and antique shops.

Reading through the second time, I thought to myself, “Lost Art Press really needs to publish a translation of this book.” Fortunately, Chris Schwarz also thought it was a great idea.

As a bonus, Pommier turned out to be a prince of a guy. The author and/or illustrator of dozens of books, he says this is one of his favorites, and the one that means the most to him personally. We talked through two batteries on my mobile phones the first time I called him up, and he has been a big help in translating the book.

It has been an honor to translate such a beautiful book and a real pleasure.

— Brian Anderson

Editor’s note: “Grandpa’s Workshop” will be available for pre-publication orders in our store on Monday. The retail price will be $22. Customers who order the book before its release will, as per usual, receive free domestic shipping. Full details on the book to come Monday.