In all my years of messing about with old workbenches and their holding devices, I haven’t had much experience with the “bench knife.”

In its original form, the bench knife is nothing more than a broken piece of a dinner knife. It is used to secure boards on the benchtop for planing their broad faces. You first butt one end of your work against a stop of some kind. To secure the hind end of the board, you hammer the bench knife into both the benchtop and the end grain of the work.

Edward H. Crussell’s fantastic curmudgeonly “Jobbing Work for the Carpenter” (1914) describes it thus:

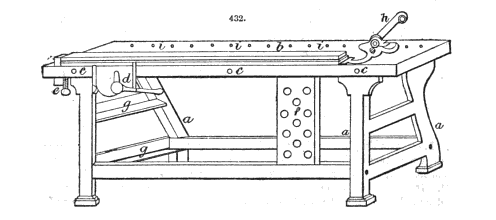

The bench knife is a tool of every-day use in Europe, but is not so well known or used in America. It is nothing but a piece of the blade of an old dinner knife about 1-1/4 or 1-1/2 in. long, and is used in lieu of a nail for holding material on the bench. It is used at the opposite end to the bench stop, being driven partly into the bench and partly into the material, as shown in Fig. 257.

For thinner stuff it is driven deeper into the bench. It is easy to apply, can be readily removed with a claw hammer, and does not mar the bench or material so badly as other forms of fastening. It is a good idea to have two or three of these bench knives because it is so easy to mislay them in the shavings.

Thanks to the worldwide butter knife shortage of 1915, ironmongers had to come up with a replacement to the simple broken knife. Most of the solutions that I see in books are a contrivance that drops into a row of bench dogs at the rear of the bench (who has a row of dogs on the rear of the bench?). Then you pull a lever that slides a thin piece of metal across the benchtop and into the end grain of the work.

I think there’s a reason that I have yet to see one of these devices in the wild: They were stupid. If you have a row of bench dogs, you could probably come up with a better way to hold the work than a mechanical doo-dad like the bench knife.

But today I saw a bench knife that I would buy and try.

Advertised in a late 19th-century magazine, this bench knife clamps to the front edge of your workbench and is infinitely adjustable. The obvious downside to this thing is that benchtop thicknesses vary a lot (1-1/2” to 4” being typical). But beyond that detail, I think the thing looks pretty smart.

— Christopher Schwarz