The catalog for Day 2 of the Fred West Tool Collection Auction is available; bids are accepted for Day 2 items through 10 a.m. on Nov. 9. (You can read a bit about Fred in this post, for the Day 1 catalog.)

— Fitz

The catalog for Day 2 of the Fred West Tool Collection Auction is available; bids are accepted for Day 2 items through 10 a.m. on Nov. 9. (You can read a bit about Fred in this post, for the Day 1 catalog.)

— Fitz

Katherine “the Wax Princess” Schwarz has a fresh batch of Soft Wax 2.0 now now available in her Etsy store. It’s my favorite finish for Shaker trays and tool chest tills, and Chris uses it on just about every not-painted chair. It looks great, smells great, is easy to apply, is non-toxic – and it makes my hands softer.

Instructions for Soft Wax 2.0

Soft Wax 2.0 is a safe finish for bare wood that is incredibly easy to apply and imparts a beautiful low luster to the wood.

The finish is made by cooking raw, organic linseed oil (from the flax plant) and combining it with cosmetics-grade beeswax and a small amount of a citrus-based solvent. The result is that this finish can be applied without special safety equipment, such as a respirator. The only safety caution is to dry the rags out flat you used to apply before throwing them away. (All linseed oil generates heat as it cures, and there is a small but real chance of the rags catching fire if they are bunched up while wet.)

Soft Wax 2.0 is an ideal finish for pieces that will be touched a lot, such as chairs, turned objects and spoons. The finish does not build a film, so the wood feels like wood – not plastic. Because of this, the wax does not provide a strong barrier against water or alcohol. If you use it on countertops or a kitchen table, you will need to touch it up every once in a while. Simply add a little more Soft Wax to a deteriorated finish and the repair is done – no stripping or additional chemicals needed.

Soft Wax 2.0 is not intended to be used over a film finish (such as lacquer, shellac or varnish). It is best used on bare wood. However, you can apply it over a porous finish, such as milk paint.

APPLICATION INSTRUCTIONS (VERY IMPORTANT): Applying Soft Wax 2.0 is so easy if you follow the simple instructions. On bare wood, apply a thin coat of soft wax using a rag, applicator pad, 3M gray pad or steel wool. Allow the finish to soak in about 15 minutes. Then, with a clean rag or towel, wipe the entire surface until it feels dry. Do not leave any excess finish on the surface. If you do leave some behind, the wood will get gummy and sticky.

The finish will be dry enough to use in a couple hours. After a couple weeks, the oil will be fully cured. After that, you can add a second coat (or not). A second coat will add more sheen and a little more protection to the wood.

Soft Wax 2.0 is made in small batches in Kentucky. Each glass jar contains 8 oz. of soft wax, enough for at least two chairs.

The Florida School of Woodwork is holding a raffle and silent auction to raise money for woodworking scholarships. This week’s silent auction item is a Kentucky Stick Chair made earlier this year by Christopher Schwarz. Plus you can buy raffle tickets to be entered to win one of this week’s raffle prizes: a Dixie Biggs carving, an L-Tomato fence from Chalkstone Woodworking and a finishing kit from Odie’s Oil). The silent auction for the chair and the raffle for this week’s prizes closes at 8 p.m. on Oct. 29 (OK – it’s a little more than a week). Click here for more information and to submit a silent auction bid and/or buy raffle tickets.

A follow the Florida School of Woodwork Instagram feed for the latest auction/raffle offerings – I spotted a few of them when I was there teaching last week; there are some excellent pieces still be be seen!

– Fitz

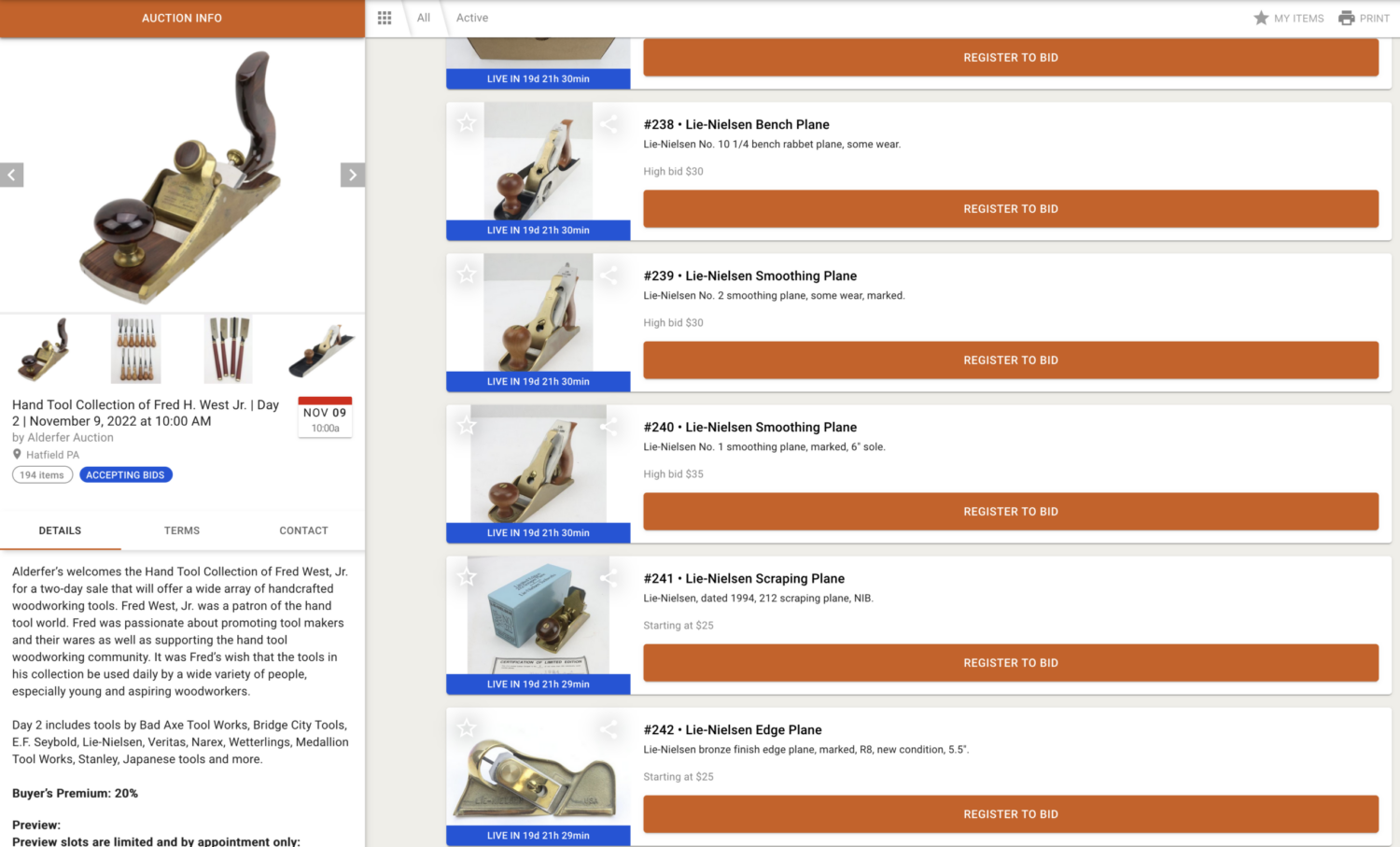

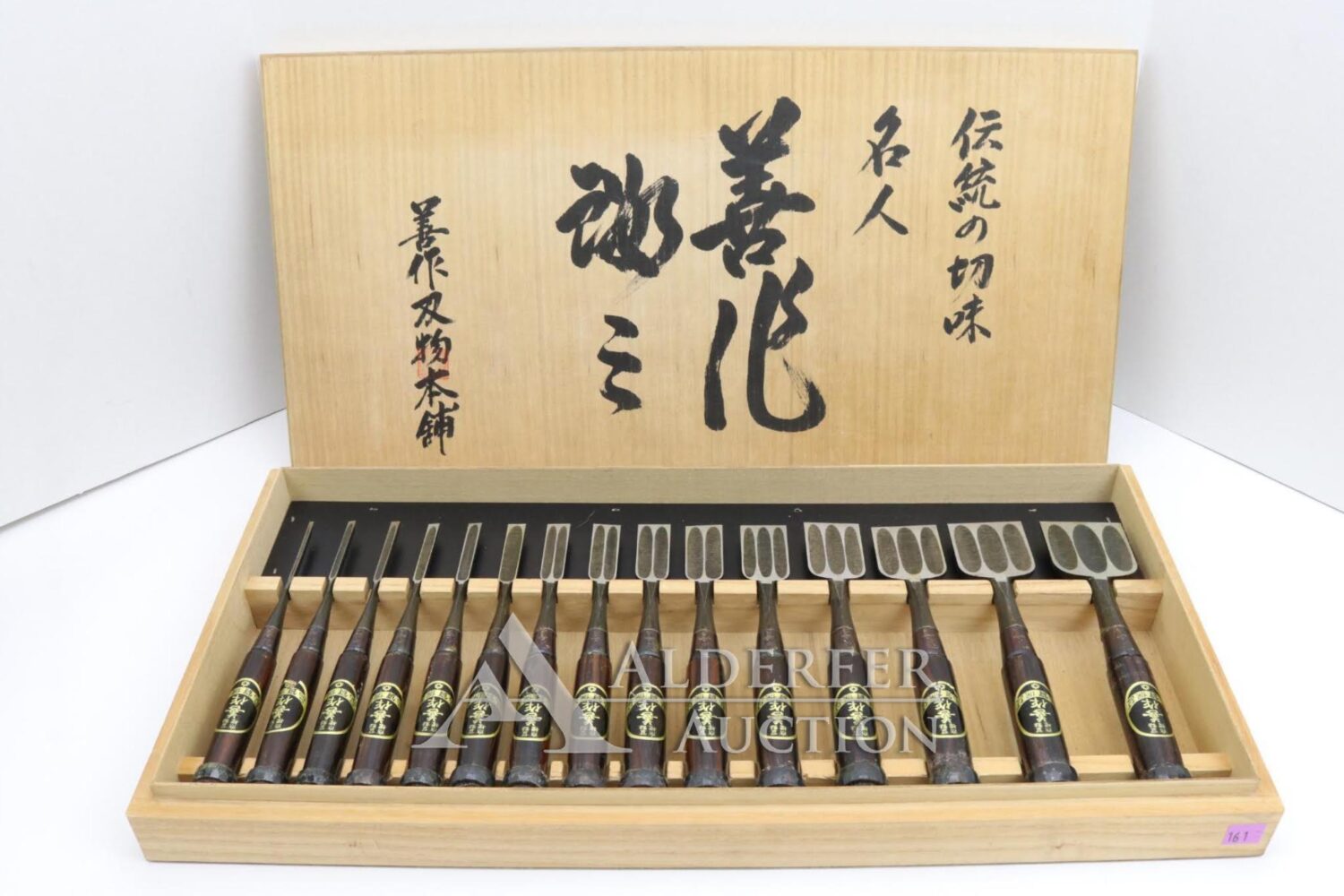

Fred West was a modern-day Medici when it came to hand tools – a true patron of the fine arts, and a driving force behind the hand-tool renaissance of the last two decades. If you were into hand tools before 2014 and attended any woodworking shows, you likely knew Fred – or at least heard him exclaiming over the inherent beauty of a fine tool, or talking about tools with his legion of friends. And if you were a maker of fine hand tools, well, you likely had Fred to thank for helping to keep you in business.

Fred loved using good tools – but he also loved supporting their makers and other users. He’d often buy multiples of new tools (and sometimes commission custom designs), then send them anonymously to woodworkers – mostly to those who couldn’t otherwise afford them – who he thought would appreciate working with them. His only request was that the tools be used.

I have two things that remind me of Fred every time I pick them up: a Vesper Tools sliding bevel (which he insisted I accept despite my vehement protestations – I’m terrible at accepting kindnesses), and the Deborah Harkness book “Shadow of Night” – he sent me his copy as soon as he’d finished reading it. (I might have liked talking popular fiction with Fred even more than discussing tools!)

Fred was one of the most gregarious and relentlessly positive people I’ve ever had the good fortune to know. Even when struggling with multiple health problems, he’d travel to hand tool conferences and events to talk tools and support toolmakers, and to hang out with his many friends. I feel lucky to have counted myself among them.

But what I didn’t quite realize was the sheer number of tools (both old and new) that Fred acquired in his all-too-short lifetime as a tool user and collector. A few weeks ago, I spoke with Susan, Fred’s former wife and mother of his daughter Eleanor, who has helped to organize an auction of Fred’s large collection. The family, she said, has realized it is time to let some things go, and to honor Fred’s work of getting tools into the hands of those who will use them. I got a preview of the auction catalog as it was in progress, and while I knew Fred bought a lot of tools, well…it turns out I had no idea quite how vast and diverse his collection was. I’m pretty sure there’s something in the collection for just about everyone – as Fred would have wished.

You can see the catalog for Day 1, November 8, here, and place bids online until the morning of November 8. From Alderfer Auction: “Auction is open for pre-bidding until Tuesday, November 8th at 10:00 AM, at which time pre-bidding will cease and the auction will go live online only at the auction center. When the auction goes live, lots will be sold one at a time, in numerical order, by a live auctioneer who will be taking bids from multiple online bidding platforms, absentee and phone bids. During pre-bidding you are able to submit a max (maximum) bid. The bidding platform or our auction staff will bid on your behalf up to the maximum bid that you have entered. Once the auction goes live if you wish to increase your bid you will have to wait until that lot opens for bidding and enter any additional bids manually.”

For more on how the auction works, and to register to bid, visit the Alderfer Auction site.

The catalog for Day 2 will be posted late this week or early next. We’ll announce it here, but you might also want to keep at eye on the site. I got a look at just some of what will be in the second catalog; you won’t want to miss it.

For questions about the auction, please email info@alderferauction.com.

The following is excerpted from “The Joiner & Cabinet Maker,” by Anonymous, Christopher Schwarz and Joel Moskowitz, from the chapter on making the dovetailed schoolbox.

In this chapter, as with the other projects in the book, Chris builds “alongside” young Thomas, the main character in the charming 1839 fictional account of an apprentice in a rural shop that builds everything from built-ins to more elaborate veneered casework. The book was written to guide young people who might be considering a life in the joinery or cabinetmaking trades, and every page is filled with surprises. You can read more about it here.

To understand how little that is certain with dovetails, let’s take an abbreviated journey through the literature. I promise to be quick like a bunny. Charles H. Hayward, the mid-20th-century pope of hand-cut joinery, suggests three slopes: Use 12° for coarse work. Use 10° or 7° for decorative dovetails. There is no advice on hardwoods vs. softwoods. F.E. Hoard and A.W. Marlow, the authors of the 1952 tome “The Cabinetmaker’s Treasury,” say you should use 15°. Period.

“Audel’s Carpenter’s Guide,” an early 20th-century technical manual, says that 7.5° is for an exposed joint and 10° is right for “heavier work.” No advice on hardwoods vs. softwoods. “Modern Practical Joinery,” the 1902 book by George Ellis, recommends 10° for all joints, as does Paul Hasluck in his 1903 “The Handyman’s Book.” So at least among our dearly departed dovetailers, the advice is to use shallow angles for joints that show and steeper angles if your work is coarse, heavy or hidden. Or just to use one angle and be done with it.

At least in my library, the advice on softwoods and hardwoods seems to become more common with modern writing. Percy Blandford, who has been writing about woodworking for a long time, writes in “The Woodworker’s Bible” that any angle between 7.5° and 10° is acceptable. The ideal, he says, is 8.5° for softwoods and 7.5° when joining hardwoods.

One Wednesday morning as I toiled with these old books, I went into the shop and laid out and cut a bunch of these dovetails. I ignored the really shallow slopes because I wanted to adopt something more angular. The 10° dovetails looked OK. The 12° dovetails looked better. The 14° tails looked better still. And the 15° looked good as well. Whatever angle you use for your joint, you can rest easy knowing that someone out there (living or dead) thinks you are doing the right thing.

One thing is certain: As dovetails have become somewhat of a cultish joint (a 20th-century phenomenon), their angles have gotten bolder. As Thomas’s slope looked too shallow for my eye, I chose 14°.