The following is by Steve Voigt, whom you might know primarily as a maker of wooden planes. But he’s also passionate about traditional finishes, and has been taking a deep dive into that subject as he works on a book for Lost Art Press. The working title is “Oil, Resin, Solvent & Pigment: Making and Using Traditional Woodworking Finishes.” We have no publication date yet, but here’s a little taste of what Steve has learned. – Fitz

A few years ago, I went looking for a period-appropriate finish for the handplanes I make, and fell into an enormous rabbit hole. Ever since, I’ve been making and researching traditional oils, paints, varnishes, and other finishes. I’ve written a number of posts and an article on the subject, and I’m currently working on a book for Lost Art Press. Along the way, I’ve found there’s a lot of confusion about boiled linseed oil (BLO). That’s understandable – it starts with the name itself. But the real problem is that the truth about BLO has become obscured behind a haze of myths and misconceptions. In this post, I’ll try to clear up some of the confusion.

A brief note on the products mentioned below. I don’t have experience with all of them, because I generally do all my oil processing from scratch, starting with high-quality, cold-pressed oil. I’ll try to be clear about what I’ve used, and what I haven’t. My goal here is to disentangle the various oils that are BLO or BLO-adjacent, so you can make informed decisions about what you want to use. I have no financial relationship with any of the companies mentioned here, and won’t make a nickel from anything you might purchase.

Modern BLO

Most woodworkers probably know what’s in the BLO available at the hardware store: Raw linseed oil and heavy metal driers (mainly manganese and cobalt). The mixture may be heated to help disperse the driers more quickly, but heat does not play any important part in the process. In the late 19th century, for reasons I’ll explain below, this stuff was known as “bung hole oil.” I’m not a fan, for a couple reasons.

First, the oil the manufacturers start with is not the high-quality, cold-pressed stuff I referred to earlier; it’s cheap oil that’s been hot-pressed and solvent-extracted. The main difference, from the user’s point of view, is that it’s going to darken or yellow over time, much more so than good oil will.

Second, there’s no way to know exactly how much cobalt and manganese are added to the linseed oil. Based on how quickly it dries, my guess is that they use a lot. This is important, because the more drier you add to a finish, the more quickly it will break down. A lot of woodworkers believe – erroneously – that any linseed oil finish is destined to turn grimy and black in the long run, and one can find plenty of furniture examples at the local antique mall that seem to prove the point. But the culprit is usually either too much metal drier or improper processing of the oil.

So there are better options available, and we’ll cover them. But first we need to talk about what BLO isn’t, and has never been…

Was BLO Ever Just Boiled?

The most pervasive belief about BLO is that back in the good old days, it was just boiled until it bubbled like boiling water, without those nasty metal driers. It’s an appealing story, but it’s pure Internet myth: Since the Middle Ages, BLO has been made with metal driers. The idea of making a fast-drying oil without driers is a good one, but it’s a modern notion, born of our concerns with toxicity and the environment, and not old or traditional.

The notion that oil was simply boiled involves a misunderstanding of both the chemistry of oil and the historical meaning of the term “boiled.” When water boils, it undergoes a phase change from liquid to gas. Oil does no such thing. If you heat linseed oil to approximately 620°F, it starts to rapidly decompose, giving off small bubbles of carbon dioxide (CO2) as it breaks down. If you’re lucky, you can hold it at this temperature for about 15 minutes before one of two things happens: Either it will turn into gelatin, or it will burst into flames. If you manage to avoid these fates, you’ll end up with a dark, viscous oil that will dry modestly faster than raw oil, and will yellow badly. It’s not a particularly desirable product, and that’s why BLO was never made this way.

So where did the “boiled” in BLO come from? Part of the answer is that the term didn’t always have the precise meaning it does today: “Boiled” was simply a synonym for heating. But it’s also important to realize that until recent times, freshly pressed linseed oil was a lot more raw than the stuff we buy in the store today, and contained a fair amount of water left over from pressing. “Boiling,” then, may simply have referred to heating the oil hot enough to boil off the residual water. In his seminal three-volume work on finishes from 1899, The Manufacture of Varnishes and Kindred Industries, J.G. McIntosh writes “a moderate heat [is] applied so as to eliminate moisture. The slight ebullition caused thereby is not to be regarded as the “boiling” of the oil, although in former days it probably gave rise to the term.”

Now, this doesn’t mean that heating oil without driers is ineffective; in fact, there is a long tradition of doing so. But these oils are more properly called “bodied oils,” and have historically been used for either printing inks or as paint additives. Heat alone has only a moderate effect on the drying speed of oil, and oil cooked without oxygen will actually dry more slowly than raw oil. To get a faster-drying oil, we have to combine heat with oxygen, sunlight or metal driers.

OK, Then How Was Traditional BLO Made?

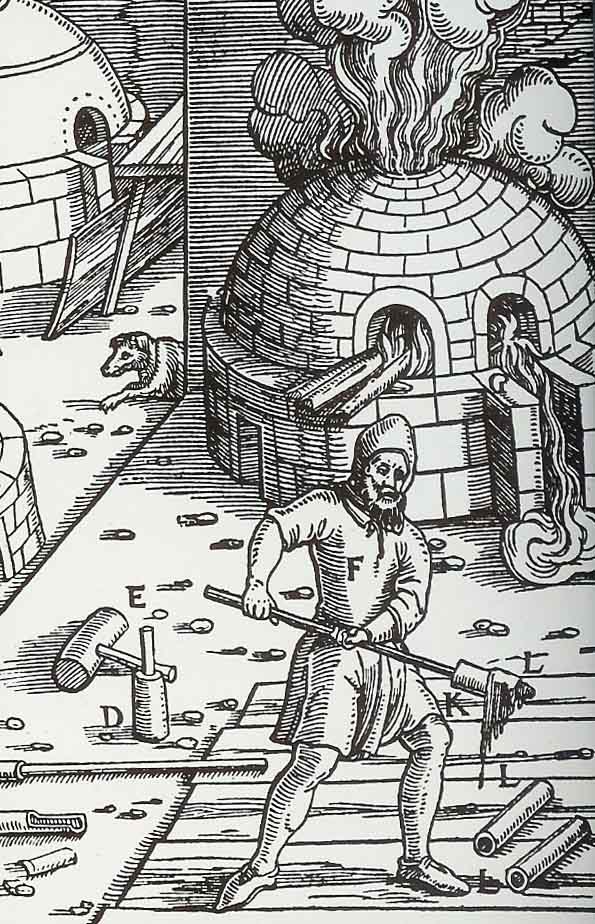

For centuries, BLO was made by cooking linseed oil with naturally occurring forms of lead oxide (PbO). The most common of these is litharge, which is still available today; you can buy it on eBay. Here are instructions from the DeMayerne manuscript, a 17th-century collection of recipes for painting, varnishing and related disciplines:

Take of the oil one half sextier, Parisian measure which weighs about 1/2 lbs, put into a newly glazed pot and throw in a half ounce of lead monoxide, stir a little with a wood spatula and let it simmer on a weak fire under a covered stove or in the yard for two hours. The oil becomes less, but only a little. Let it settle thoroughly and pour the thickened oil off by tipping the pot, and keep it for all kinds of uses.

Note the instruction to “let it settle thoroughly.” Litharge is only partially soluble in oil, so you want it to sink to the bottom of the pot before you decant the oil. But in addition to speeding up drying, litharge also plays another crucial role: It actually refines the oil.

Today, most people buy linseed oil in its raw, unrefined form. But historically, it was much more common to refine the oil before using it, because raw oil contains a lot of foreign material, called mucilage (sounds and looks like mucus!) that your oil is better off without. Oil can be refined in lots of different ways: It can be centrifuged with acids or alkalis, which is common in industrial refining, but it can also be simply shaken with water, a practice common in pre-industrial times. Or, it can be cooked with litharge, which acts as a precipitant, causing the mucilage to separate. The result is a dark colored but clean oil that dries quickly. That’s traditional BLO.

In the late 19th century, liquid driers (containing lead, manganese or cobalt) that fully dissolved in oil were invented, and a simpler, cheaper method of making BLO took hold: Driers were simply poured into the top of a barrel of oil. The driers would sink down, mixing with the oil, and the resulting “boiled” oil would be withdrawn through a spigot at the bottom of the barrel, known as the bung hole. Thus, the name “bung hole oil” was born. Unlike traditional BLO, bung hole oil is just raw oil, with all its mucilage, and a lot of cobalt and manganese. When it was first introduced, it was held in low regard. The state of New York even passed laws to discourage its manufacture. But faster and cheaper usually wins out in the marketplace, and today, nearly all BLO is bung hole oil. The only exception I’m aware of is Rublev’s dark drying oil, which is made in the traditional manner. I haven’t used it – I’d rather not mess with lead in any form – but if you’re curious, it’s available. Keep in mind that lead is particularly toxic for children.

If you want a lead- and mucilage-free BLO that’s far better than the bung hole oil from the hardware store, it’s easy to make your own. Go to an art supply store and buy a bottle of alkali refined linseed oil. To 500 ml oil, add 5 ml Japan drier, and mix thoroughly (500 ml is just more than a pint, and 5 ml = 1 teaspoon). “Japan drier” is an imprecise term, and different brands contain different mixes of driers, but Klean Strip from the hardware or big box store will work fine. If this dries too slowly, add a little more drier, but remember, in the long run, the less the better.

If you don’t want to mix your own, Heron paints sells a pre-mixed version that looks very similar (I haven’t tried it myself, but I’ve heard good things about their products).

If you’d rather avoid heavy metal driers in any form, read on – there are a number of options available.

BLO Alternatives

When I started woodworking in the 1990s, BLO from the hardware store was pretty much the only option available, but now there are many different brands of processed linseed oils you can buy. Some of these are good alternatives to BLO, and some are not. There are many I haven’t tried, but here are a few I’m familiar with.

Tried & True Danish Oil, unlike most other so-called Danish oils, is 100-percent linseed oil, with no driers or volatile organic compounds (VOCs). I spoke with Joe Robson, the founder of the company, who confirmed that it’s a refined oil that has been heated and oxidized. It’s a nice, light-colored oil that dries faster than raw oil, but not as fast as BLO. You’ll need to apply thin coats and wait 1-2 days between applications. If that’s not a problem, you’ll find that it gives far better results than BLO.

Ottosson boiled linseed oil dries faster than Tried & True, and is made from cold-pressed oil. I’ve used it and like it, but the company is a little guarded about what’s in it. On the product page is stated that “the raw material is cold pressed stored and absolutely pure raw linseed oil which is heated to approx. 140° C.” However, on another page, they write that “both oxygen and metal salts are added to make the product more reactive.” I wrote to Ottosson for clarification, but didn’t receive a response. More generally, I get a little irked by their claim that the oil is purified by storing it for six months. This doesn’t refine the oil; there’s as much mucilage in these oils as there is in fresh oil (try washing some, and you’ll see). Despite these reservations, I think Ottosson BLO is a big improvement over hardware store BLO.

There are some processed oils that are better avoided if you’re looking for BLO alternatives. “Stand oil” is made by cooking linseed oil at high temperatures in an oxygen-free environment, so it actually dries more slowly than raw oil. It’s useful as an additive to paint, but not ideal if you’re looking for a transparent wipe-on finish. “Blown oil” is made by blowing air through the oil until it becomes very viscous. It dries more quickly than raw oil. While blowing can be used to make a nice oil for woodworking, commercial blown oil isn’t ideal; like stand oil, it’s best used as a paint additive. Sun-thickened oil is the same deal. You can sun thicken oil to whatever viscosity you want, but the stuff you can buy is very thick and, once again, is probably better used as a paint additive.

Making Vs. Buying

You may have noticed a theme in the previous paragraph – the gap between what could be commercially available, and what is. We’ve all been trained to view finishes as something you buy, which means you’re stuck with whatever is available. But once you start thinking of finishes as something you make from raw materials, a world of new possibilities opens up. Oils, paints and varnishes can all be made to have the characteristics you want, rather than what some giant multinational company thinks you should want. This is a big topic – far too big for one blog post – but I’ll continue to explore and write about it in the coming months and years.