Chris Schwarz suggested I invite Helen Welch to be interviewed for the Lost Art Press blog. “She is a “[bleep]ing badass,” he wrote. “A tool nerd. Funny and sharp as hell.” So I wrote her by email. She sent back the following reply.

“If nothing else (other than saving lives), this lockdown has given us all a chance to do stuff we wouldn’t normally do. Things I’ve discovered during this time:

“I hate sourdough.

“I do not like to work from home. A one-bedroom apartment is no place to make the kind of mess I enjoy in the workshop.

“Practicing my golf swing indoors has aged the fixtures and fittings.

“The homemade wines I made two years ago are now drinking well. A rare case of serendipity.

“Danish is a very odd language but I’m enjoying the challenge.

“Videoing myself is a special kind of torture, only topped by having to edit the damn thing. Gruesome. Likewise Zoom, Skype etc.”

Then she said sure, she’d be happy to do the interview.

I knew I was going to enjoy our phone call.

Most woodworkers familiar with Helen know her through the London School of Furniture Making, which she founded and has operated since 2013. “It’s nowhere near as august as the London College of Furniture,” she laughs, acknowledging the similarity between the two names. Woodworking schools pride themselves on a range of qualities, from their size and diversity of course offerings to their cultivation of individual students’ skill in artistic design, or their faithfulness to particular historical traditions. The London School of Furniture Making is tiny, with just four benches, which allows Helen and her fellow instructor, Sam Brown, to give each student an extraordinary level of attention. Course offerings are varied in terms of topic and duration, aimed primarily at amateur makers. Short courses build specific skills; project courses offer opportunities to put them into practice. Beyond this, students can pay a daily fee to come in and simply use the benches and tools, as well as pick her brains. If the London School of Furniture Making were to claim a special niche, it might be that these characteristics make learning there unusually customized and accessible.

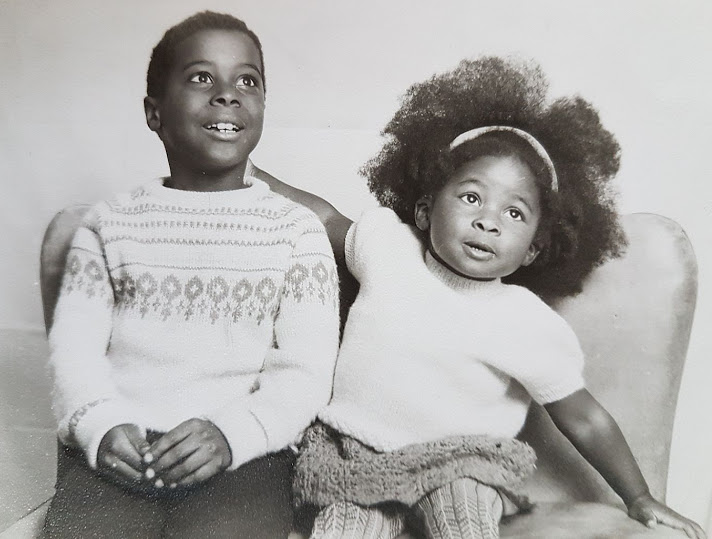

Helen started the school after decades of work in the trades. She was born and raised in North London, where her father sold film (the kind for cameras in the pre-digital era) at Boots, a nationwide pharmacy chain. Her mother had a variety of jobs that included work in a perfume factory but spent most of her career in retail sales at John Lewis, one of Britain’s best loved department stories. Helen’s older brother, Maurice, is a passionate photographer who’s all about electronics and gadgets.

At the age of 11 Helen made a conscious decision to go to a girls’ school. “I didn’t want to have to fight for my teachers’ attention,” she explains. By the time she entered sixth form (senior high school in the United States), the school had become co-ed. In 1984, as she was preparing to take her A-Levels in biology, chemistry and business studies, she says, “all my fears about being overlooked came to fruition. I was simply exhausted from the struggle, so I left.”

Later that year she returned to the school to attend a careers fair, most of the offerings at which were “not interesting, just banks and boring things, not what I envisaged doing…” But as she wandered around the booths, a couple of people at a tiny stall in a corner called out “Come chat to us! If you’re not doing anything, why don’t you come and work in our woodwork-cum-training college?” Why not? she thought, and jumped right in.

The business was a collaboration of four people – two men and two women – who shared a shop in the north London area called Kentish Town. “Splinter Group was a training center which carried out woodworking jobs in the local community,” she told me. “I was paid £25 per week as part of the government’s Youth Training Scheme.” The shop was a large space with an eight-bench hand tool room and a separate machine shop, all on the first floor (which we in the States refer to as the second floor) of a Victorian-era light industrial building. The work entailed a mixture of teaching/learning and making. “If it was wood, they did it. They would bring their trainees on site as well as building in the shop.” While working there Helen made a set of stairs; a complicated play frame for a children’s play center; a table and shelves, and a toolbox for the tool set they gave her. “I remember thinking it was quite a good mix of skills and different woodworking projects. It gave me an idea of what was possible — there are all sorts of things I can make with these skills.”

After about six months at this cooperative shop, Helen spent a year doing a variety of work, “including making some fake French antiques for a guy I met in a pub.” She worked in building maintenance for a local women’s center and ended up applying for an apprenticeship in carpentry and joinery with Camden Council, where she spent three years – one year in building maintenance and repairs; one year of renovation and restoration on jobsites; and one year in a joiner’s shop making windows and doors. She earned her City & Guilds Certificate in carpentry and joinery in the late 1980s, specializing in (of all things) building forms for cast concrete structures, a skill she hasn’t used since. As soon as she had the certificate, she left the council job. “’This is a three-year prison sentence which is now up,’” she remembers thinking – “three years of misogyny and racism. I have very few happy memories [of that time]. It was tiresome, but I worked hard to not let it scar me.”

Helen took a job as a building inspector for the Building Control Department in Camden and then Islington, where she worked for five years. As someone who had worked in the trades, she says, “I realized there was a split between the people who came in from university and those from the trades. I quickly made friends with the ex-carpenters and the ex-plumbers. We were more collaborative when working with the chippies (Brit-speak for carpenters) on site, whereas some of our colleagues just wanted to read the letter of the law. [The work of building inspectors] is more of a problem-solving exercise,” she says, alluding to the kind of considered and constructive approach that anyone in construction or remodeling appreciates. She sums up that experience as “five years of interesting developments in my understanding of construction and the legal side [of that business].” But in the end, she felt “I was too young to be trapped telling people what to do. I missed being back in the workshop making things.”

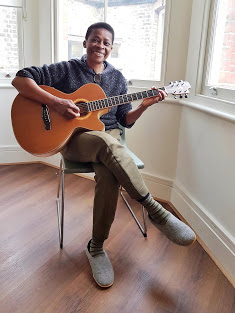

So she took herself off to the London Metropolitan University (formerly the London Guildhall University/London College of Furniture, and before that, Shoreditch Technical Institute) to study guitar making. “I had a fantastic three years there,” she says of that time, which allowed her to develop her skills at a far higher level. She graduated from the program thinking “Wow, this is amazing – and there’s absolutely no career in it!”

Being a determined individual in need of income, Helen started making built-ins and doing carpentry. She had no shop; she worked in people’s homes. “[It was] me, my van and tool kit. Me constructing things on site. It worked for a good number of years.” Her business came exclusively by word of mouth. Her customers were mostly married couples with a couple of kids, “quite well-paid people in their mid-30s who’d just bought their first proper house and wanted to have some built-in cupboards.”

She supported herself by means of this work, without a shop, for about 10 years, starting around 1994. She had a typical complement of trim carpentry tools: a portable Festool table saw (made up by fitting her track saw into a table), a jigsaw, planer, power tools, and used a couple of “trestles” (sawhorses) topped with a sheet of plywood for a bench. “Not a lot of hand tools,” she says, then throws in: “When I think about it now I wonder how did I manage to last 10 years doing that? Eight-by-four sheets of MDF. Hateful!”

As a side gig ever since completing her training in lutherie she taught part time at London Metropolitan University, City and Islington College, Women’s Education in Building and The School of Stuff, to name a few – some evening classes, sometimes one day a week. She enjoyed teaching but she still had no intention of doing so in her own set-up.

Around 2004 Helen finally got a workshop in a space shared with a fellow who went by the name Bob Smoke (not his real name); he made props and designed special effects for film and television. Although she describes it as “an enormous hangar of a place which was freezing cold in winter and hot in summer, never comfortable,” the new work situation gave her the opportunity to retrieve her better equipment from the storage unit where she’d been keeping it, and to make more interesting things than painted built-ins. Jobs still came entirely through word of mouth.

By 2010 she’d decided it was time to commit to what she calls “a proper workshop.” She looked around. For £600 a month she could get a place that wasn’t much bigger than the living room in her apartment. But for £750 she could get something much better: a shared workspace in a complex of industrial warehouses built around the 1970s in Tottenham, North London, that’s home to 15 cabinetmaking businesses. She went to see the couple of guys who had the space to let, Alistair Williams and Joe Ridout – they run a furniture and cabinetmaking company – and she ended up renting the space. Since then, she says, “I really haven’t looked back.” When they moved into a bigger unit she asked if she could take on a couple of students as a new venture – “something sustainable that makes me feel like I’m having a good time…something that will not give me sleepless nights and leave me feeling resentful to[ward] customers.” She found that there were lots of people eager to learn, people who valued her flexible set-up. Her fledgling venture grew, and she decided it was going to be a school. Happily, Joe and Alistair were and still are very supportive.

Most students find her through the school’s website. Classes have been cancelled since mid-March. She’s spent her time at the shop alone streamlining things and improving ergonomics – much-needed improvements to what she calls the previous “controlled chaos,” while also “playing with my tool kit, as opposed to the school’s. I’m a tinkerer.” The last thing she made was a solid silver plane, just for fun. “I wanted to try my hand at jewelry, working with precious metal clay.” After firing you end up with 99 percent pure silver.

Most other businesses in the building have been carrying on as usual. For those doing custom furniture and cabinetmaking, there’s plenty of space to keep the recommended distance from others; for teaching detailed hand skills, not so much. She hopes to resume classes in June.

— Nancy Hiller, author of Making Things Work

I am so impressed with the women who have been profiled here, all of them exude a spirit of determination,independence and a zest for living life on their terms.

Bravo,bravo, bravo!

I had the great pleasure of making Helen’s acquaintance last year, when we were both in Mark Harrell’s five-day saw sharpening class at the London IWF; she is indeed a truly delightful person, in a most agreeably [bleep]ing badass way!

Mattias

I’m not trying to be clever, or being sarcastic – just curious. Why does it take 5 days to learn how to sharpen a saw?

Douglas,

First things first: I am *not* an authority on saw sharpening (if I were, I would hardly have taken a five day class on the subject), nor a very experienced saw sharpener, either. So please add pinches of salt according to taste to what I am about to say on the subject!

The short answer to your question is, it doesn’t. It takes both less time and much, much more. One can pick up the basic principles of the thing in a couple of hours, while to actually *learn* (meaning, to really know what your doing, and why, and be able to do it consistently) to sharpen is likely to take, well, I won’t say “a lifetime”, but at least a very substantial number of saws taken in hand, and in any case rather more than five days.

The slightly longer answer for this specific five-day class, given by Mark Harrell (of Bad Axe Tool Works), at least the one I attended last year was perhaps in total half a day or so of theoretical instruction on saw assembly and dissasembly, saw tooth geometry, and jointing, filing and (hammer) setting tools and techniques.

Another two-and-a-half days were spent in what you might call tutored practicing (i.e. applying the techniques in question) on practice plates and/or saws in need of TLC. Most of the final two days were then spent assembling, setting, jointing, and sharpening a Bad Axe back saw, i.e. starting out with a toothed (but not set) plate, back, handle and fasteners, and carrying out all the operations required to make that into a finished saw.

If you are interested in more details, I think you can find the curriculae of Mark’s two- and five day seminars on the Bad Axe Tool Works website.

In any case, as a saw sharpening tyro, I found it well worth spending five days at it in a classroom. The big difference, I’d say, with putting in the same amount of practice at home is that it is tutored, i.e. someone who really knows what they’re about is there to check your work while in progress, help correct errors before they become bad habits and answer all your beginner questions as they come to mind. Plus you’re really there to do nothing but that for 40+ hours.

I hope this answers your question!

Cheers,

Mattias

The reason I asked the question was that I remembered coming across a 40 minute duration video by Paul Sellers that ‘taught’ how to sharpen a saw; somewhat briefer than a five day course. However, I am much more inclined to give weight to your ‘short answer’ than the quick “now you know how to do it” video tuition offered by Sellers.

I read your slightly longer answer as being a three day course with an added two days for specialisation, and it seems to be eminently sensible.

I abandoned western saws, not long after I started woodworking, in favour of Japanese saws with the hardened teeth. Given the almost trivial cost of the blades I was never interested in spending the extra money to buy Japanese saws that could be re-sharpened. However, lately I have been regularly dulling the teeth on my large ryoba saw that I’m using to rip cut large pieces of karri and sometimes I think that, maybe, sharpening Japanese saws is not so far away from a good idea as it used to be.

Thank you for the reply you provided. It was clear, succinct and completely answered my question.

Warm regards,

Douglas

One of the women I most want to meet – so very impressive!

Me, too. I have this idea of traveling to the UK with F in a few years when he’s slightly older and I really think I’m going to have to be there for something like a month. There are so many people and places I want to see and meet up with, including Helen, and then I also want to do some nice relaxing hiking with my son. Maybe parts of the wall. Hiking Hadrian’s Wall… in a kilt. It’s something I’ve wanted to do for years now.

But definitely, going to Norf London to meet Helen and see all of the amazing tools she’s collected (something Nancy didn’t touch on enough, I think!) is high on the list.

On the matter of attention paid to tools or other aspects of these profiles, I write about the material our conversations bring up. To some degree this is up to the interview subjects; to some degree it depends on what I know about them as woodworkers and people. It’s fascinating (to me) to see what people choose to discuss. For my part, as someone who has made her career as a woodworker, and whose daily realities have been closer to Helen’s than to those of most woodworkers in the publishing industry, I found her account of how she got into the field and has made her way through it over the decades a refreshing treat. Maybe you should interview her for a podcast about tool collecting. 🙂

Probably not a podcast, but… maybe something for Quercus!

Hope I didn’t come across as a nitpick, Nancy. I love love love your interviews. They’re fantastic. I just also know that Helen has shown some amazing little tools on IG over the months and I bet she has MOAR! I want to see them! 🙂

It would be fab if you got a story about her in the magazine. 🙂

So glad to know about her and to hear of her interesting life towards her current endeavors in woodworking. A good sense of humor is such a bonus. I am sure she is an awesome teacher.

I’m pretty effing blown away that she worked 10 years without a shop. That’s impressive.

For the sort of work she was doing at the time I find it very similar to quite a lot of the jobs I have done. The vehicle becomes the big rolling tool chest and each job site is the next workshop. If you are lucky you can even work under a covered area and not have to carry every #$%* thing into the house. Space costs money, sometimes an awful lot when not being used consistently and you live in a high rent area. It does wear a bit thin after a while. The comment about mdf was spot on too , although I find the term hateful to be quite reserved and perhaps not convey a deep enough level of disdain 🙂 . I find even more impressive is Helen’s ability to see the end goal with her City and Guilds certificate and suck up all the crap that must have been chucked her way by all the drongos (blunt tools) . These interviews are great.

Thanks for this note! You made me laugh. Much appreciated.

Thanks, again, Nancy. I’ve been saving these bios for my dessert, when I get to sit down and really savor them.

I had never heard of Helen before, and I’m happy to have this introduction. She has a fascinating history. It makes me appreciate being involved in a craft where folks such as Helen can thrive. She’s an inspiration.

Now I need to go look up The School of Stuff. I love the name.

Yes, doing built-ins all over London without access to a shop would take a special kind of patience and resourcefulness. Helen’s really inspiring.

Wonderful!!!!

Another excellent profile. Thank you.

Great piece on Helen. You’ve managed to capture what a fine human being she is.

Helen is a person of immense quality. I make furniture and my introduction into this and what got me hooked was Helen and her lovely school of making. It’s a uniquely fantastic experience, people come from all over the world to be taught there. Helen is a wonderful teacher. She is extremely knowledgable and skilled but is able to explain even the seemingly most complicated process with clarity and patience. I loved everyday I was at the school, I can understand why Mark goes there just to hangout! Helen’s enthusiasm, energy and humour are infectious. I’m utterly impressed by Helen’s career so far and am not surprised that she’s thrived through some incredibly trying jobs. Her banter and gentle chiding are an asset in situations where sharp tools and physical power are features. I hope teaching can resume as soon and as safe as is possible so many more people can be treated to a dose of Helen.

It’s me in the photo centre of Helen and Sam.

Known Helen for 5 years in that short time has become one of my best friends. She is an exceptional person.

Loved this article, massive chunk missing where Helen inspired and helped so many young women, including myself, at WEB (women education in building) and WAMT (women in manual trades) to break into the industry