Importance of Getting Your Article Right First and then Advertising it Emphasized by the Experience of the Manufacturers—How E.C. Atkins Started a Business that Now Employs 1200 Men in the Home Plant—Sought Publicity Through the Trade Papers First—Now Uses General Magazines and Weeklies.

“Get something worth selling— then use printers’ ink.”

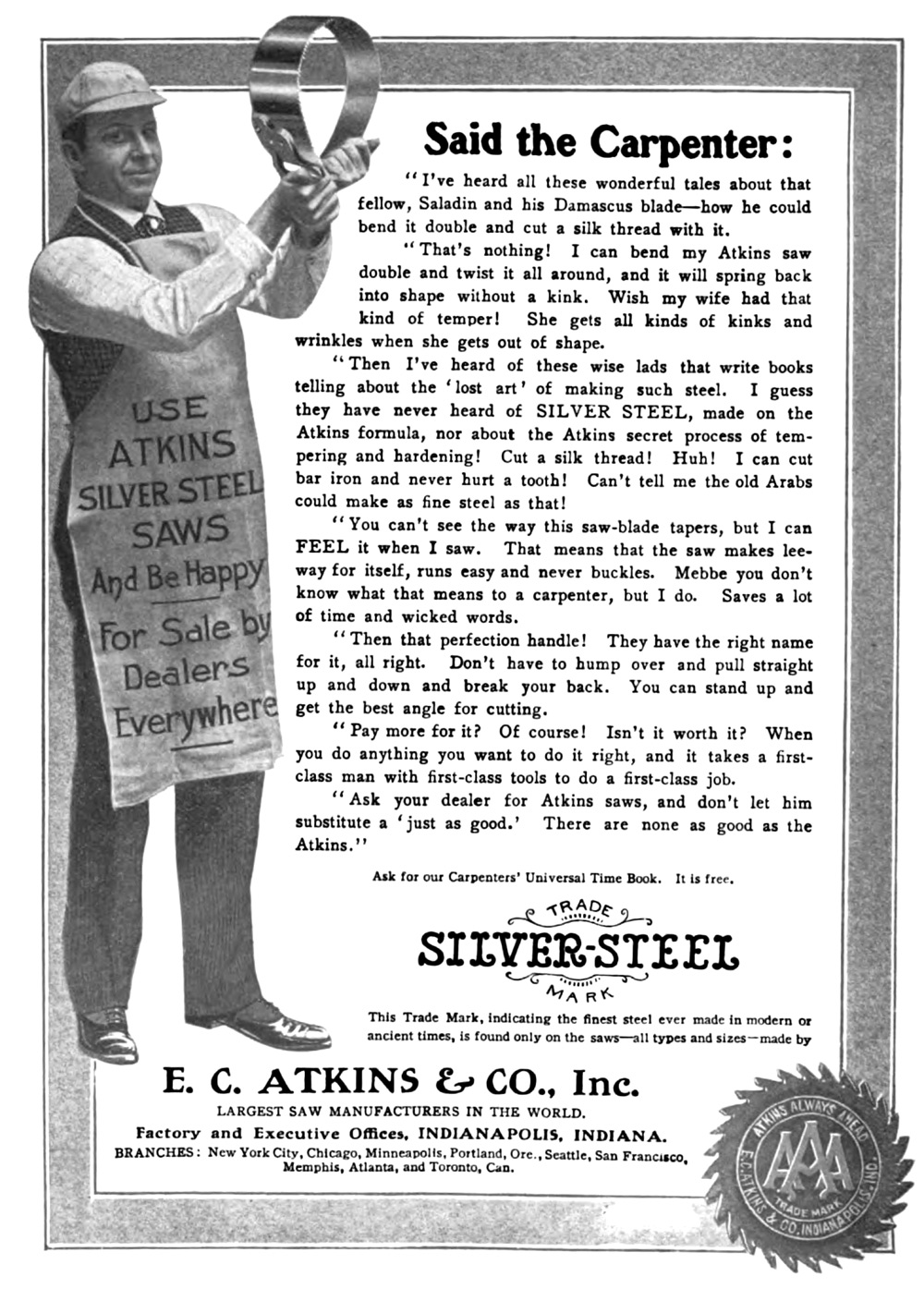

This is the Golden Rule of business which E. C. Atkins & Co. followed for many years before they got the “something.” Then they applied the stimulant which produces business wealth — printers’ ink. The sum total is, the company is now one of the greatest producers of saws in the world and some say the greatest. Year after year the Atkins output increases in volume and the expenditures for advertising space grow apace.

The story of Atkins advertising is necessarily the story of Atkins saws, of the man who made both possible. As a maker of saws, the Atkins plant in Indianapolis is a pioneer in the development of the industry as it is known to-day. It was among the first to turn raw steel into a finished saw that the railroads, the trail-makers of civilization, might cut their paths through the woods of the Middle West.

With the Atkins saws, too, was produced some of the first lumber for homes, wagons, bridges, barges and boats of the pioneer settlers in the Mississippi Valley, for there was still much of a trackless forest about him when E. C. Atkins began to make saws. The Atkins works was doubtless the first in its line of industrial activity to see the wealth that is to be wrought out of printers’ ink.

But the company—rather, E. C. Atkins—spent about twenty years perfecting a saw before it began fertilizing its honest product with advertising. The first lumber trade journals of America carried ads of the Atkins saws. The company, too, was the first to make missionaries of the popular magazines to get word of its saws to men who are, and who may be, users of such an implement.

This same company is among, if not the first maker of saws to strike off the main highway of advertising to the by-path of agricultural journals to preach the doctrine of what it makes and sells. “A. A. A.” — “Atkins Always Ahead” — has long been a user of the county seat weekly. In many ways this Indianapolis company has put publicity to the test and found it good.

One does not have to burnish fact with fiction to get a glowing story of business activity and integrity, to find an industrial romance in this Indianapolis concern which makes saws—nothing but saws—and which seems only to have crossed through advertising the frontier of trade possibilities.

In his lifetime E. C. Atkins, whose day runs to the present through the medium of his saws, has probably done as much as any other man to provide the material for sheltering Americans in comfortable homes, to build the cabin in the clearing, the apartment house in the city.

He was born in Connecticut in 1833 and twelve years later began to learn the making of saws in his uncle’s factory. His pay was $1.25 a week. It went to the family of his widowed mother, as did his overtime pay. When seventeen years old he knew the making of a saw from a to z, as it was known in that day, and he became assistant superintendent of the uncle’s factory at the stupendous salary of $1,000 a year.

In 1855, when about twenty-two years old, he was carried by the tide of emigration to Cleveland, O., and opened a saw factory of his own. There was a greater need for saws in the oak and walnut forests of Indiana, and in 1856 he went to Indianapolis. His chief asset was a reputation as the best saw-maker in the young country.

The few hundred dollars in his pockets went for steel. He built his first tempering furnace with his own hands. There was no mortar in its construction and it fell down after the first firing. The making of saws by the known processes was tedious hand-work. During the first few years in Indianapolis, the Atkins “plant,” sheltered under a rough shack of about coal-shed dimensions, burned several times. But the fires did not consume the saw-maker’s energy. He soon set up his anvil and tempering furnace again.

Mr. Atkins kept his own books, and looked after his correspondence. He smithed saws four or five days a week, spending one or two in the tempering room, doing the work with a helper and without machinery. He was not then dreaming of founding an industry which to-day employs 1,200 men in the home plant, which has ten branches over the United States with ten to forty men in each, and has a new factory in Canada.

He was not then looking to the time when the Atkins saw would be a great user of advertising space. But he was putting in the foundation work of both these things. His first intent was on producing the best saw that man could make. A counterfeit would soon be found out in the hard woods of Indiana—it would take the genuine steel to do the work of the mills and crosscut woodsmen.

Every Atkins saw bears the words “Silver Steel” on it. Back in the pioneer days, a salesman for the Atkins factory was on the rounds of the Michigan woods. He found in use a saw with a new tooth which two Michigan woodsmen had made. The salesman sent word to the Indianapolis maker that if he would sell crosscut saws in Michigan, Mr. Atkins would have to own the patent on the new tooth, or contrive a better one.

Mr. Atkins went to Michigan at once. He carried home the new saw and the patent rights, and the two men who made it entered his employ. A new steel and a better one was necessary for the new tooth. Mr. Atkins, who, as the years went by, had developed as a metallurgist as well as a saw-maker, prepared a formula for the quality of steel desired in the new saw.

He went to England to have this steel made, and was told that the price would be so high the woodcutters of the United States could not buy the saws.

“That is the kind of steel razors are made of,” the Englishmen said.

“Then that is the kind of steel for Atkins saws.” the Hoosier answered. Mr. Atkins named the metal “silver steel” and during his life, as is the case with the Atkins company now, it was his boast that no other saw metal has been made to equal it.

As the Atkins factory grew in its first twenty years, its product sold on merit alone. Mr. Atkins and his helpers invented and made the machinery with which the saws were made. A laboratory was opened in the factory to establish standards of hardening and tempering processes. Scientific instruments of a delicate kind, necessary to the tempering process, were produced by the Atkins mind and hand. When the right quality of steel had been found, when the right saws with teeth of the right strength and “pitch” were produced, the Atkins factory sought for a medium to spread the word of its product.

The first issues of the American Lumberman, The Southern Lumberman, The St. Louis Lumberman, The Mississippi Valley Lumberman, and several other of these trade journals, carried advertisements of Atkins saws, and the ads are still running in these publications. For about as many years an ad has been carried in Iron Age and other hardware journals.

A few years ago the Atkins company began to specialize hand and other small saws. Twenty years ago a band saw was hardly known. The Atkins company is making them to-day seventy feet long and twenty inches wide. A different medium from a trade journal was desired to get these specialties into the hands of consumers, and nearly five years ago the Atkins company began to use the popular magazines.

There were at that time no other saw specialists in the field and saw ads in magazines were a new thing. The Century, McClure’s, Scribner’s, World’s Work and Munsey’s are some of the monthlies which have been used year by year, and two of the weeklies are Collier’s and the Saturday Evening Post.

N. A. Gladding, sales manager of E. C. Atkins & Co., says the company has year after year increased its appropriations for magazine space. “We realize that there is not a limit to our possibilities in the way of a market. This leads us to think that we have only started with our advertising. We use a goodly quantity of space in county seat newspapers to support our local agents, preparing electrotypes in the home office for these newspapers. We frequently change the series of electrotypes. We find the demand for Atkins saws constantly increasing, and in this we find that advertising pays the saw-maker if he makes a saw of the right quality.”

The Atkins magazine advertising has from the beginning been placed through the Russell Seeds Agency, of Indianapolis. “The Atkins company,” said Mr. Seeds, “began its advertising campaign under what I regard as ideal conditions. It had spent many, many years getting a product of very high quality. It has for years had a splendid system of distribution of its product to dealers and consumers. It had the full confidence of dealers before it began to use the magazines.”

“We prepare two kinds of copy for the Atkins saw. In the magazines the ads are of the kind a busy man can ‘read on the run.’ A different kind of copy goes to the agricultural papers, which is giving satisfactory results. Large space is used in the farm journals and it is filled with reading which discusses the qualities of Atkins saws and why they cost a little more than saws of other make. We reason that a farmer has the time to read an ad from beginning to end, even if it is a long one, while the city reader of a magazine does not. The Atkins company has supported its advertising with ample capital and a sound, sane business organization. Advertising with this sort of foundation can do nothing else but succeed.”

Printer’s Ink – December 16, 1908

-Jeff Burks

Reblogged this on Stu's Shed.