The design of the deluxe edition takes the ambiance of the 18th-century book for its design cues; early 20th-century book designers, most notably Bruce Rogers, termed this “allusive typography.” Hallmarks of the Rococo book include the substitution of type ornament for woodcuts, a rationalized system of titling (breaking the chapters into discrete parts, and giving them subheadings), and the use of Baroque typefaces. Each of these changes marks the progress toward the industrialized production techniques of the 19th-century: the change from hand-press platen to the cylinder press; rationalization of scientific inquiry; a narrowing of the letterforms, together with shorter descenders and a tendency towards a more brilliant style of cutting. This Baroque style in type design marks its beginning with Hungarian Miklós Kis in the 1690s, continues with the French founder Pierre Simon Fournier in the 1740s, and finds its nadir with Johann Michael Fleischmann’s work in the 1760s for the Enschédé Foundry. Furniture makers can find a similar stylistic transition from William & Mary through Federal.

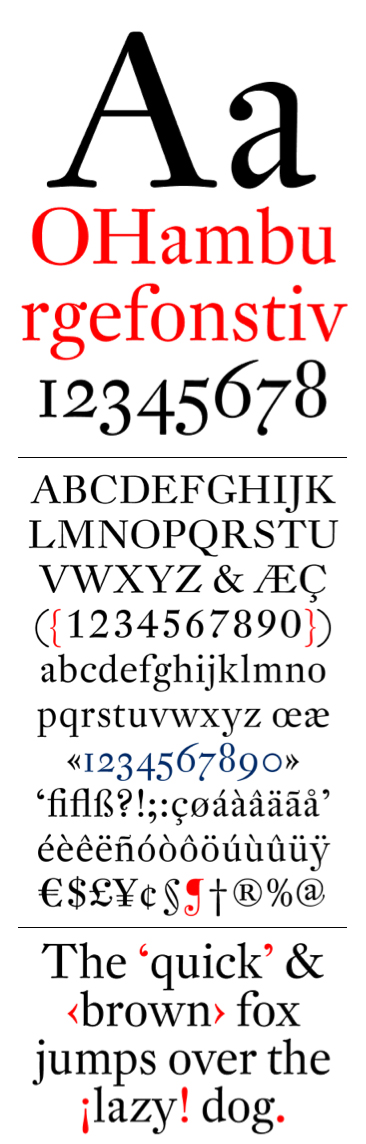

Fleischmann types, finding themselves eclipsed by the modern styles, fell out of fashion and disappeared from use; but for an edition like “To Make as Perfectly as Possible,” his types are perfect. Happily in the early 1990s, the Dutch Type Library was able to find Erhard Kaiser in Leipzig to create the digital drawings using the original copy of Enschédé’s 1768 specimen book.

Types created during the 400 years of printing were entirely cut by hand, letter by letter, and each size was adjusted for its optical size. After the invention of the pantograph, most types were created using only one master set of drawings. This has continued to be largely the case with the current group of digital fonts. A few fonts have been designed with optical scaling in mind: a set of drawings for sizes 12 point and below, known as Text; a Display set for 14 point and above. DTL Fleischmann is one of these. In the deluxe edition of “To Make as Perfectly as Possible,” the footnotes, sidenotes and the editor’s comments on process have were set in the Text version; Roubo’s text and most of the headings were set using the Display set.

As part of the international support for the Roubo project we are grateful to Frank E. Blokland at Dutch Type Library in Amsterdam for loaning us a copy of DTL Fleischmann to use in the design of the Roubo volumes.

— Wesley Tanner

Next: Tending the Typographic Garden.

>

Sample looks nice.

Remaining copies still “on hold”?

I will release details on this point this evening.

I’m still waiting on my copy of the Deluxe. I hope you save a couple until all of us who purchased the book months ago, receive ours. If there is a USPS screw up, I would be majorly disappointed if there was no back up.

Of course we will replace lost and damaged copies. We always have and always will.

Egads! I need help.

I found reading that interesting and enjoyable.

Is there such a thing as typeface anonymous? A 12 point bold program with a serif, maybe?

i wasn’t trying to question your integrity. Obviously, this is a book of limited supply, and while I know everyone is pushing you to do it, I just would hate for all copies to be released, before those of us that paid long ago were assured a copy.

Your integrity is without question. You have to admit, there has been shipping issues in the past. And yes, you stood by the orders, no questions asked.

We do everything we can.

We cannot speak for the people who are between you and us, but we always replace damaged or missing books, even if the shipper absolves responsibility.

Surely you can understand one’s paranoia when dealing with a book that will never be published again, and is virtually sold out.

I have nothing but positive things to say about LAP, I support the company both verbally and financially.

I certainly wouldn’t have minded a lengthier post on this subject as I find fonts fascinating. When I was an art student we had a visiting typographer visit campus one day. I was prepared for utter boredom (I was a metals and photography major who didn’t have much dealing with illustration etc). Much to my surprise it was very interesting and while it didn’t foster enough interest to overcome my Mediterranean laziness to action, it did prompt an interest that remains.

Some comparison examples between modern and vintage fonts would have been excellent in illustrating what Mr. Tanner is describing.

Did I use any verbs?

Thanks for these posts, Wesley; I hope there are many more to come. I only wish I had a copy of the deluxe version to compare. I’m very interested in hearing about the decisions made regarding type and page design in the proportional shrinking of formats; if leading, type sizes, margins, headings, &c in the trade edition follow from the deluxe (and from the first), or if these were only of pragmatic consideration, given the complexity of the average page.

Joel,

The plates in the Deluxe edition are the same size they were originally printed. The Standard edition reproduces them at 60%. The typographic design of each edition is different; for editorial reasons the side notes are in both editions, which may give the illusion that they are the same design. The contemporary typefaces used in the Standard edition, both serifed and sans, are Scala, by Martin Majoor (1993), and the chapter titles use Michael Harvey’s Ellington (1990). The design intent of this edition was to make it readable in the workshop environment, were hopefully you are right now.

Sadly Michael Harvey passed away last week after 82 very creative years; an interesting review of his life’s work was written by Paul Shaw for Print Magazine’s web site: http://www.printmag.com/featured/michael-harveys-life-of-letters/