I don’t collect tools, books or even Hummels (he said, throwing up a little in his mouth).

Instead, I like to collect clarity.

Ever since I was a kid, I’ve always gathered little scraps of paper filled with notes jotted down from the books I’ve read, the lectures I’ve attended and the friends I’ve had beers with. I am a great admirer of people who can frame their ideas in a compelling way using as few words as possible – even if I vehemently disagree with them.

I turn these phrases over and over in my mind, like a fine object. I examine the workmanship, look for flaws and study the social context in which they were made. I also like to place these them against other ideas to see if new meaning emerges.

And that is why I post these quotations on the Lost Art Press blog and pair them with images. I don’t mean to confuse or upset. And I don’t use them to indicate my own personal thought processes, mood or aura (I’m trending orange this morning, by the way).

Instead, the blog is a way to record these quotations (I sometimes lose my scraps of paper), and the response from others is always interesting.

So about that Elbert Hubbard quote on obedience. Here’s why I posted it with that image.

1. This is from Elbert Hubbard, the guy who wrote “Jesus was an Anarchist” (1910), a spiritual founder of the American Arts & Crafts movement, a book maker and a soap salesman. Was the guy a genius? A sellout? How does that quotation square with what I know about Hubbard’s philosophy? Does his “Message to Garcia” tick you off or make you nod your head in agreement?

2. Hubbard founded the Roycrofters, an organization of craftsmen who specialized in making all sorts of beautiful handmade and sometimes eccentric objects. Like many Arts & Crafts proponents, the idea was to mimic the medieval guilds.

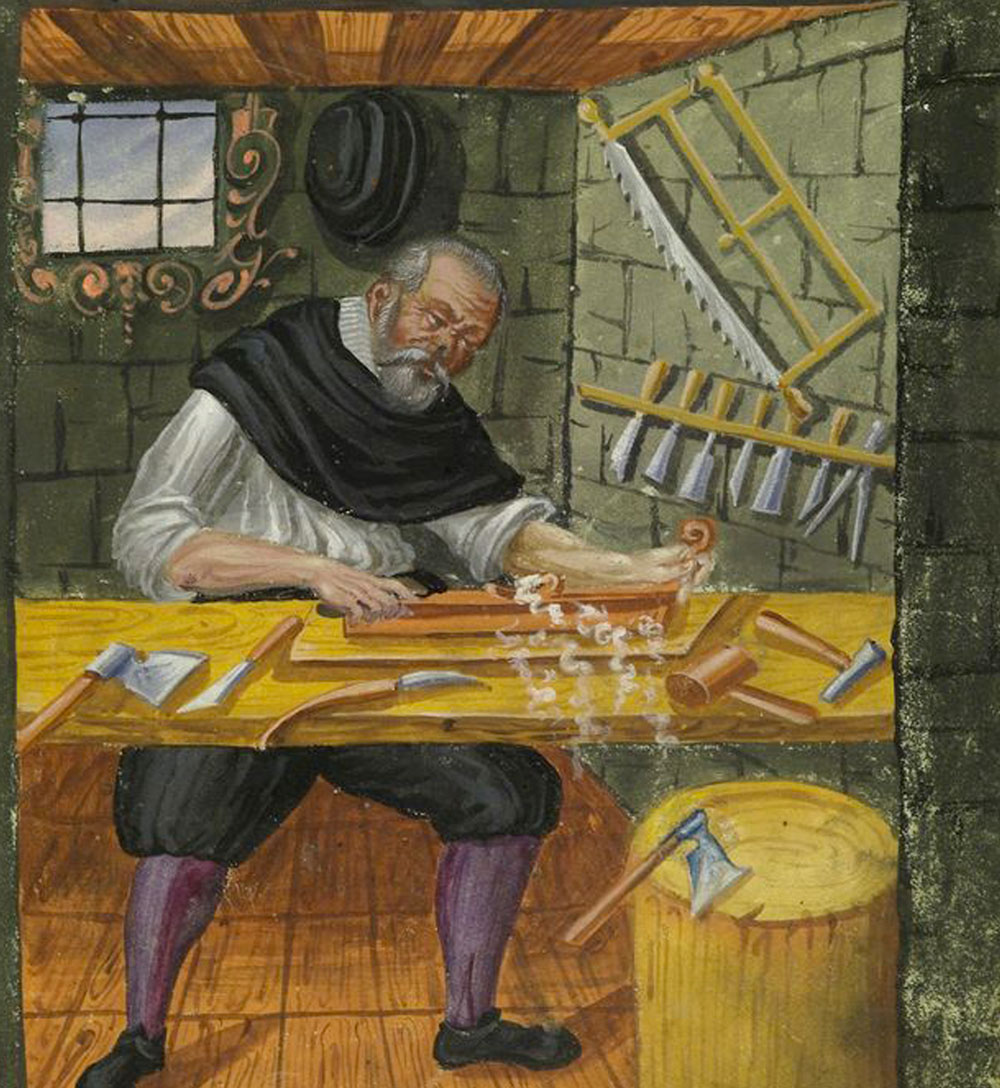

3. Which takes us to the image, which is from “Die Hausbücher der Nürnberger Zwölfbrüderstiftungen,” naturally. It’s a collection of images of craftsmen from many trades that began in 1388. I’ll let you run the web pages through Google Translate yourself, but these books were created for an interesting reason — they were part of a retirement home for impoverished craftsmen.

So for me, this image and this quotation make me think about the meaning of obedience as it relates to craft, especially now that I am out of a job.

So there you have it. I don’t mean to be opaque, but I also don’t teach people how to cut dovetails by going over to their house and building them a dovetailed tool chest.

OK, now I’ve marked your baselines for you.

— Christopher Schwarz

Like this:

Like Loading...