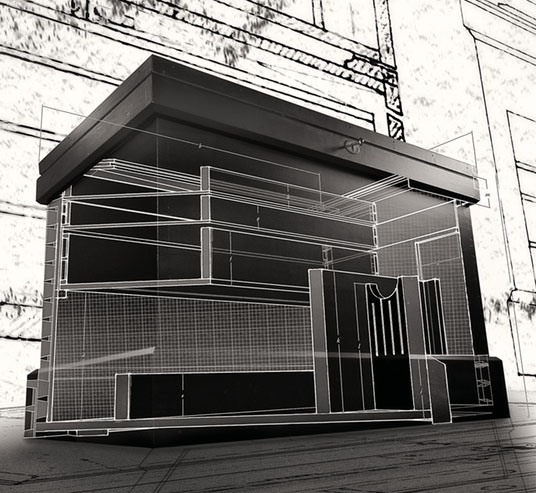

Some readers are sure I was a little drunk when I designed the lower sliding till of my tool chest. Why didn’t I allow the lowest till to slide all the way forward? Heck, all I had to do was lower the wall of the sawtill an inch.

When researching tool chests for “The Anarchist’s Tool Chest,” there were several features I saw on old chests that I considered adding to mine.

1. Putting a hinged lid on the top sliding tray. Why didn’t I do this? I had a lid like this on my first chest and disliked it. Horizontal surfaces get covered with stuff – particularly in a shop with several woodworkers. I was always cleaning off the lid to get to the tools below. So I nixed this lid.

2. Putting a sawtill on the underside of the lid of the chest. Why didn’t I do this? I have a sawtill on my old chest and am ambivalent about it. That particular sawtill – based on Benjamin Seaton’s example – likes to eat the horns of nice saws for breakfast. Plus I really wanted that space for my sliding trays.

3. Adding a sliding panel or door above the well of bench planes. This feature appears in many old chests and is touted as a way to protect your bench planes and to have a shelf in the chest to hold items overnight, such as your shop apron.

That sounds reasonable. So I built it.

And that is why the lowest tray of my chest doesn’t slide all the way forward. I built a nice raised-panel door and hinged it to the wall of the sawtill. The door came to rest on the lowest runners and acted as a stop for the lowest tray.

It looked clever on paper but it was immediately obvious that the door was a dumb thing. It impeded the travel of the trays above and added more hand motions for me to get to the bounty at the bottom of the chest.

So I removed the door.

Why didn’t I remake the guts of the chest to allow the lower tray to slide all the way forward? I’ve always meant to do that. It would be a quick fix – all of the chest’s interior parts are fit with friction and nails. But I haven’t felt the need. I simply keep the lowest tray at the back and the other trays at the front – it works fine.

There’s a lesson here, really. In dealing with the woodworking public since 1996 I can report that we like to complicate things. We add features or decorative details more readily than we will take them away.

Resist the urge to add cupholders to your tool chest. Instead, first try taking things away from a design.

And if you have to be drunk to do something that crazy, then so be it. I won’t judge.

— Christopher Schwarz