Photo courtesy of Drew Langsner.

The following is excerpted from “Good Work: The Chairmaking Life of John Brown,” by Christopher Williams. It’s the first biography of one of the most influential chairmakers and writers of the 20th century: Welshman John Brown.

______________________________________________________________________________________________________________

John Brown by his own admission wasn’t a fan of finishing. (See Good Woodworking issue 63.)

“American chairs are really polished. Typically, the finish is paint. Without exception all the American chairmakers I meet ask me how I get my finish. I fail to understand this because it is the least interesting part of my work. It’s an aggravating necessity, as far as I am concerned.”

Here are the finishes that John Brown regularly used. These were always applied before assembling the chair.

‘Welsh Miserable’

This term could be seen as a criticism of the Welsh and brown furniture. But I always took it in jest. During the ’80s and ’90s, brown was deemed to be the accepted colour of country furniture. Newly made furniture was also brown. JB secretly wanted to paint his chairs or leave them blonde. So “Welsh miserable” was his private joke.

JB’s recipe for this was a dark oak stain from a tin. Once it was dry, he applied a coat of sanding sealer. He would rub this back with fine sandpaper. He then applied two or three thin coats of shellac button polish and left the finish to dry overnight, if time allowed. He lastly applied a coat of dark oak wax polish with #0000 wire wool.

The Spirit of Wales

This finish was a favourite of his. It probably was the only finish he was enthused about as it brought out the artist in him! JB wrote, “The effect is not meant to reproduce an antique finish, but to try to capture the Spirit of Wales.”

JB would first apply a dark green water-based dye to the raw timber – always remembering to raise the grain a few times beforehand. When it was dry, he sanded it smooth and didn’t worry about sanding through the green. He then applied a dark brown stain over the green. When it was dry, he gave it a coat of sanding sealer. He sometimes added a coat of button polish before applying dark brown or black wax.

The finished chair had a greenish, brown/black appearance. In a certain light it’s spectacular.

Blonde

JB described a natural-coloured chair as a “blonde chair.” He had two approaches to this.

If the natural colour of the grain was needed to be kept as bright as possible he used a white shellac polish. He would first apply a coat of sanding sealer. Then he gave it two or three coats of white shellac. In most cases he didn’t thin the polish; it was used direct from the bottle. Great care was needed as a high gloss could be attainted very quickly. This in turn gave the chair a glassy look. Finally, he applied a clear wax polish with #0000 wire wool.

He would sometimes (in his words) want to “kill the lightness.” By adding a few coats of shellac garnet polish over the sanding sealer this gave the chair a honey colour and a warm glow. He would finish up with a light, oak-coloured paste wax.

JB predominantly used the combination of oak and elm for the bulk of his chairs. Each species complemented the other colour-wise. If a steambent ash bow was added to the mix, it was coloured to blend in with the oak and elm. He achieved this by first making a strong pot of tea. The tea was applied to the ash arm before the sanding sealer and subsequent finish.

Oil

I only saw JB use oil on occasion. The tenons on the legs, stretchers and sticks were covered in masking tape to prevent the oil from penetrating. The oil was applied and left to dry before he applied a coat of paste wax with #0000 wire wool.

To me it looked lacklustre compared to the shinier shellac finish.

I loved the “Good Work” book. And this is a nice chance to ask a question about it.

What is sanding sealer? I see that there is both water-based and oil-based sanding sealer out there. Which kind did JB use?

Have also been curious about JBs use of sanding sealer. Why not just use shellac?

To John Griffin – I don’t believe water based sand sealer was available at the time – at any rate it wasn’t much good when it first came on the market. So probably used oil based.

Sanding sealer, at least in my area, is usually ‘clear’ shellac or polyurethane with a filler like zinc stearate to help fill the pours in the wood. You have to puzzle through the label, though. Sometimes, it really is only super blonde shellac.

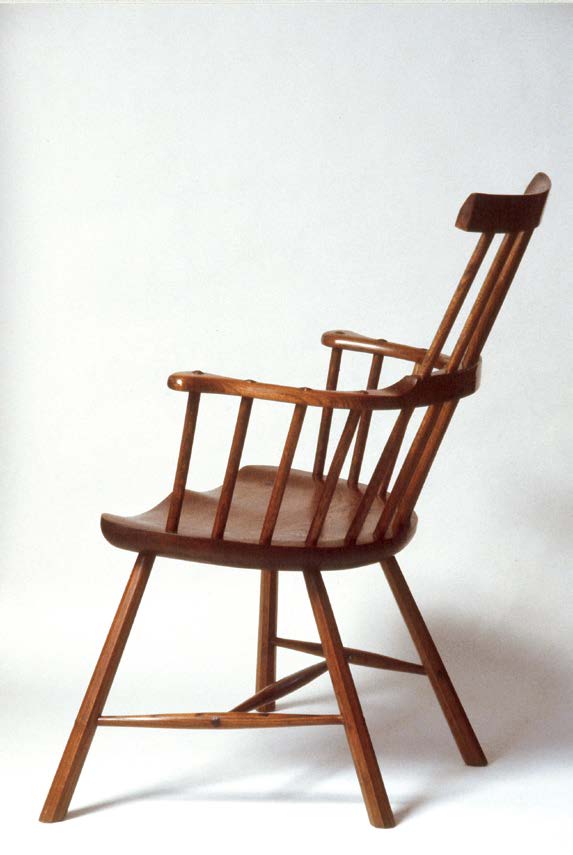

I know this blog post is primarily aimed at the finishes employed, but I thought I’d chime in again to state how the sight of a super high backed Cardigan Chair is never able to slip past me without drawing me into a second or third look. 👀 To me at least, it’s probably one of the most elegant of chairs. I

It depends on the project, but for chairs, a large enough suitcase in which to flat pack it works, or we have boxes that can be packed and go on the plane as an added bag (typically $50-$100, depending on the airline).

It is nice to see a well respected maker, that also finds finishes aggravating. No work is complete with out it, but that does not by default make it fun.

Quote from the top, “These {finishes} were always applied before assembling the chair.” How did he get the glue to hold? Assuming he protected the components, how could he keep the finish out of the mortises?

I guess/hope it was shellac sanding sealer and not synthetic.