The following is by Steve Voigt, whom you might know primarily as a maker of wooden planes. But he’s also passionate about traditional finishes, and has been taking a deep dive into that subject as he works on a book for Lost Art Press. The working title is “Oil, Resin, Solvent & Pigment: Making and Using Traditional Woodworking Finishes.” We have no publication date yet, but here’s a little taste of what Steve has learned. – Fitz

A few years ago, I went looking for a period-appropriate finish for the handplanes I make, and fell into an enormous rabbit hole. Ever since, I’ve been making and researching traditional oils, paints, varnishes, and other finishes. I’ve written a number of posts and an article on the subject, and I’m currently working on a book for Lost Art Press. Along the way, I’ve found there’s a lot of confusion about boiled linseed oil (BLO). That’s understandable – it starts with the name itself. But the real problem is that the truth about BLO has become obscured behind a haze of myths and misconceptions. In this post, I’ll try to clear up some of the confusion.

A brief note on the products mentioned below. I don’t have experience with all of them, because I generally do all my oil processing from scratch, starting with high-quality, cold-pressed oil. I’ll try to be clear about what I’ve used, and what I haven’t. My goal here is to disentangle the various oils that are BLO or BLO-adjacent, so you can make informed decisions about what you want to use. I have no financial relationship with any of the companies mentioned here, and won’t make a nickel from anything you might purchase.

Modern BLO

Most woodworkers probably know what’s in the BLO available at the hardware store: Raw linseed oil and heavy metal driers (mainly manganese and cobalt). The mixture may be heated to help disperse the driers more quickly, but heat does not play any important part in the process. In the late 19th century, for reasons I’ll explain below, this stuff was known as “bung hole oil.” I’m not a fan, for a couple reasons.

First, the oil the manufacturers start with is not the high-quality, cold-pressed stuff I referred to earlier; it’s cheap oil that’s been hot-pressed and solvent-extracted. The main difference, from the user’s point of view, is that it’s going to darken or yellow over time, much more so than good oil will.

Second, there’s no way to know exactly how much cobalt and manganese are added to the linseed oil. Based on how quickly it dries, my guess is that they use a lot. This is important, because the more drier you add to a finish, the more quickly it will break down. A lot of woodworkers believe – erroneously – that any linseed oil finish is destined to turn grimy and black in the long run, and one can find plenty of furniture examples at the local antique mall that seem to prove the point. But the culprit is usually either too much metal drier or improper processing of the oil.

So there are better options available, and we’ll cover them. But first we need to talk about what BLO isn’t, and has never been…

Was BLO Ever Just Boiled?

The most pervasive belief about BLO is that back in the good old days, it was just boiled until it bubbled like boiling water, without those nasty metal driers. It’s an appealing story, but it’s pure Internet myth: Since the Middle Ages, BLO has been made with metal driers. The idea of making a fast-drying oil without driers is a good one, but it’s a modern notion, born of our concerns with toxicity and the environment, and not old or traditional.

The notion that oil was simply boiled involves a misunderstanding of both the chemistry of oil and the historical meaning of the term “boiled.” When water boils, it undergoes a phase change from liquid to gas. Oil does no such thing. If you heat linseed oil to approximately 620°F, it starts to rapidly decompose, giving off small bubbles of carbon dioxide (CO2) as it breaks down. If you’re lucky, you can hold it at this temperature for about 15 minutes before one of two things happens: Either it will turn into gelatin, or it will burst into flames. If you manage to avoid these fates, you’ll end up with a dark, viscous oil that will dry modestly faster than raw oil, and will yellow badly. It’s not a particularly desirable product, and that’s why BLO was never made this way.

So where did the “boiled” in BLO come from? Part of the answer is that the term didn’t always have the precise meaning it does today: “Boiled” was simply a synonym for heating. But it’s also important to realize that until recent times, freshly pressed linseed oil was a lot more raw than the stuff we buy in the store today, and contained a fair amount of water left over from pressing. “Boiling,” then, may simply have referred to heating the oil hot enough to boil off the residual water. In his seminal three-volume work on finishes from 1899, The Manufacture of Varnishes and Kindred Industries, J.G. McIntosh writes “a moderate heat [is] applied so as to eliminate moisture. The slight ebullition caused thereby is not to be regarded as the “boiling” of the oil, although in former days it probably gave rise to the term.”

Now, this doesn’t mean that heating oil without driers is ineffective; in fact, there is a long tradition of doing so. But these oils are more properly called “bodied oils,” and have historically been used for either printing inks or as paint additives. Heat alone has only a moderate effect on the drying speed of oil, and oil cooked without oxygen will actually dry more slowly than raw oil. To get a faster-drying oil, we have to combine heat with oxygen, sunlight or metal driers.

OK, Then How Was Traditional BLO Made?

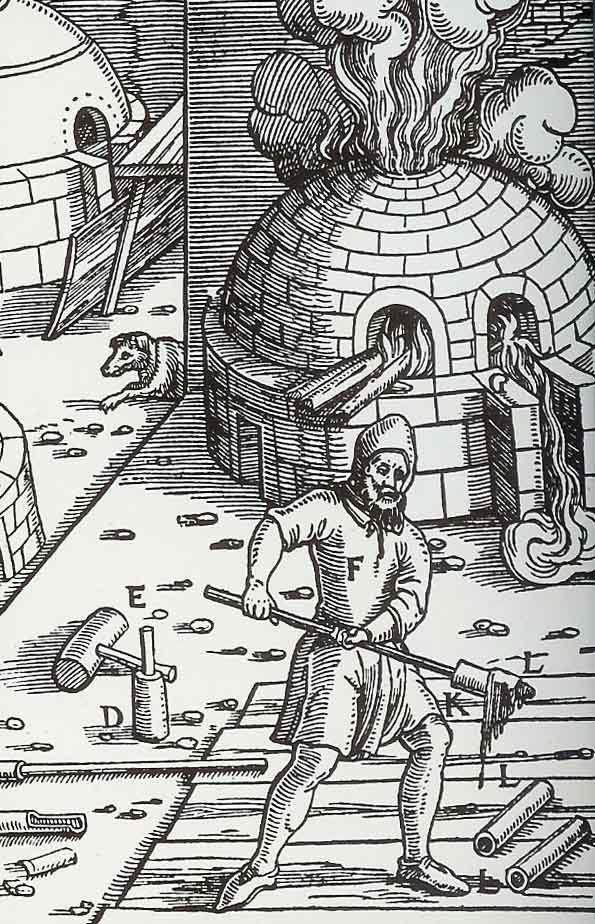

For centuries, BLO was made by cooking linseed oil with naturally occurring forms of lead oxide (PbO). The most common of these is litharge, which is still available today; you can buy it on eBay. Here are instructions from the DeMayerne manuscript, a 17th-century collection of recipes for painting, varnishing and related disciplines:

Take of the oil one half sextier, Parisian measure which weighs about 1/2 lbs, put into a newly glazed pot and throw in a half ounce of lead monoxide, stir a little with a wood spatula and let it simmer on a weak fire under a covered stove or in the yard for two hours. The oil becomes less, but only a little. Let it settle thoroughly and pour the thickened oil off by tipping the pot, and keep it for all kinds of uses.

Note the instruction to “let it settle thoroughly.” Litharge is only partially soluble in oil, so you want it to sink to the bottom of the pot before you decant the oil. But in addition to speeding up drying, litharge also plays another crucial role: It actually refines the oil.

Today, most people buy linseed oil in its raw, unrefined form. But historically, it was much more common to refine the oil before using it, because raw oil contains a lot of foreign material, called mucilage (sounds and looks like mucus!) that your oil is better off without. Oil can be refined in lots of different ways: It can be centrifuged with acids or alkalis, which is common in industrial refining, but it can also be simply shaken with water, a practice common in pre-industrial times. Or, it can be cooked with litharge, which acts as a precipitant, causing the mucilage to separate. The result is a dark colored but clean oil that dries quickly. That’s traditional BLO.

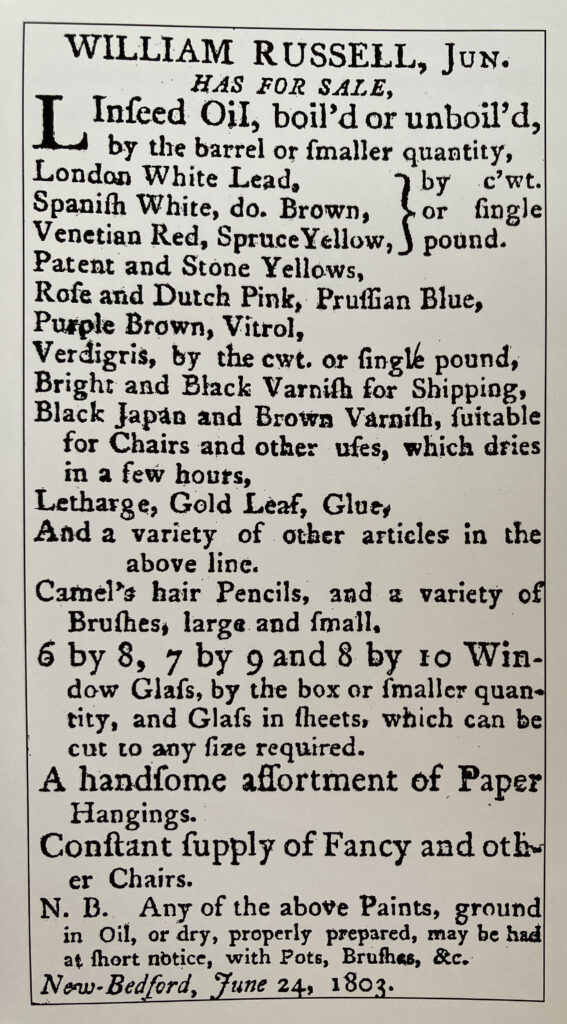

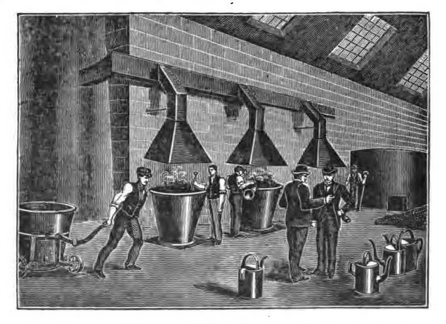

In the late 19th century, liquid driers (containing lead, manganese or cobalt) that fully dissolved in oil were invented, and a simpler, cheaper method of making BLO took hold: Driers were simply poured into the top of a barrel of oil. The driers would sink down, mixing with the oil, and the resulting “boiled” oil would be withdrawn through a spigot at the bottom of the barrel, known as the bung hole. Thus, the name “bung hole oil” was born. Unlike traditional BLO, bung hole oil is just raw oil, with all its mucilage, and a lot of cobalt and manganese. When it was first introduced, it was held in low regard. The state of New York even passed laws to discourage its manufacture. But faster and cheaper usually wins out in the marketplace, and today, nearly all BLO is bung hole oil. The only exception I’m aware of is Rublev’s dark drying oil, which is made in the traditional manner. I haven’t used it – I’d rather not mess with lead in any form – but if you’re curious, it’s available. Keep in mind that lead is particularly toxic for children.

If you want a lead- and mucilage-free BLO that’s far better than the bung hole oil from the hardware store, it’s easy to make your own. Go to an art supply store and buy a bottle of alkali refined linseed oil. To 500 ml oil, add 5 ml Japan drier, and mix thoroughly (500 ml is just more than a pint, and 5 ml = 1 teaspoon). “Japan drier” is an imprecise term, and different brands contain different mixes of driers, but Klean Strip from the hardware or big box store will work fine. If this dries too slowly, add a little more drier, but remember, in the long run, the less the better.

If you don’t want to mix your own, Heron paints sells a pre-mixed version that looks very similar (I haven’t tried it myself, but I’ve heard good things about their products).

If you’d rather avoid heavy metal driers in any form, read on – there are a number of options available.

BLO Alternatives

When I started woodworking in the 1990s, BLO from the hardware store was pretty much the only option available, but now there are many different brands of processed linseed oils you can buy. Some of these are good alternatives to BLO, and some are not. There are many I haven’t tried, but here are a few I’m familiar with.

Tried & True Danish Oil, unlike most other so-called Danish oils, is 100-percent linseed oil, with no driers or volatile organic compounds (VOCs). I spoke with Joe Robson, the founder of the company, who confirmed that it’s a refined oil that has been heated and oxidized. It’s a nice, light-colored oil that dries faster than raw oil, but not as fast as BLO. You’ll need to apply thin coats and wait 1-2 days between applications. If that’s not a problem, you’ll find that it gives far better results than BLO.

Ottosson boiled linseed oil dries faster than Tried & True, and is made from cold-pressed oil. I’ve used it and like it, but the company is a little guarded about what’s in it. On the product page is stated that “the raw material is cold pressed stored and absolutely pure raw linseed oil which is heated to approx. 140° C.” However, on another page, they write that “both oxygen and metal salts are added to make the product more reactive.” I wrote to Ottosson for clarification, but didn’t receive a response. More generally, I get a little irked by their claim that the oil is purified by storing it for six months. This doesn’t refine the oil; there’s as much mucilage in these oils as there is in fresh oil (try washing some, and you’ll see). Despite these reservations, I think Ottosson BLO is a big improvement over hardware store BLO.

There are some processed oils that are better avoided if you’re looking for BLO alternatives. “Stand oil” is made by cooking linseed oil at high temperatures in an oxygen-free environment, so it actually dries more slowly than raw oil. It’s useful as an additive to paint, but not ideal if you’re looking for a transparent wipe-on finish. “Blown oil” is made by blowing air through the oil until it becomes very viscous. It dries more quickly than raw oil. While blowing can be used to make a nice oil for woodworking, commercial blown oil isn’t ideal; like stand oil, it’s best used as a paint additive. Sun-thickened oil is the same deal. You can sun thicken oil to whatever viscosity you want, but the stuff you can buy is very thick and, once again, is probably better used as a paint additive.

Making Vs. Buying

You may have noticed a theme in the previous paragraph – the gap between what could be commercially available, and what is. We’ve all been trained to view finishes as something you buy, which means you’re stuck with whatever is available. But once you start thinking of finishes as something you make from raw materials, a world of new possibilities opens up. Oils, paints and varnishes can all be made to have the characteristics you want, rather than what some giant multinational company thinks you should want. This is a big topic – far too big for one blog post – but I’ll continue to explore and write about it in the coming months and years.

Discover more from Lost Art Press

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.

Great post Steve. Looking forward to more of these and your book.

Great to hear there’s a book coming on this subject, it’s a rabbit hole I’ve also been preoccupied with for the last year or so in the context of buildings rather than furniture.

On the subject of aging oil – Peter Lewis, a paint maker in Sydney, ages his raw cold pressed linseed oil for a year before making paint with it and reckons it makes a big difference to quality and drying time. His website isn’t great but he does know paint back to front and is good for a chat on the phone. Bit of a heads up for Australians looking for linseed oil paint too.

My own raw oil, cold pressed by a farm a couple of hours drive away, has thrown a precipitate just sitting in a jar for a few months, washing it is much more effective though.

Fascinating. Thank you very much for this work.

I can belive this is something that you of all people, Peter, will be interested in. You are a treasure of the world, PF, and I wish I could be your lifetime patron. Thanks for all your efforts over the years.

This is in his wheel house.

Very happy and excited about this book. I think there is a niche that it will fill. I own one of Steve’s planes and it is of the best quality.

Can’t wait for the book! I’ve been experimenting with pure Tung oil and have poked around the internet trying to figure out how to get it to dry. There is a lot of conflicting information, it’s hard to sort out the facts. I feel like I’m reinventing the wheel.

Tung oil is…complicated, but useful. It will be covered.

Great read, thanks for sharing. I use both stand and sun thickened oil when I am doing on my artwork. A couple of years ago I tried mixing some stand oil with pure turpentine and wax for a wipe o type finish, and it turned out pretty nice, it did take a few days to really cure out, but he finish was a nice satin look and feel and to date there has been very little yellowing. I would be interested in seeing book published on this. I have experimented with the following and found Poppy oil: A slower drying oil known for its non-yellowing properties and its suitability for pale colors. Safflower oil: Similar to poppy oil but with a slightly faster drying time. Walnut oil: A non-yellowing drying oil with a slower drying time, often used as an alternative to linseed oil. These oils of course were purchase in small quantities and not sure the cost of quarts or gallons.

Thanks again.

When you mentioned Kleen Strip from the box stores, did you mean the Kleen Strip brand of Japan drier or the actual paint stripper?

Japan drier. I wouldn’t put paint stripper in linseed oil!

I’ve romanticized about making my own finishes, including actually blending the typical 1:1:1 pure tung oil and store-bought varnish and mineral spirits for many years for turnings. But landing on the Tried & True varieties many years ago has proven good for me. Light-light-light coats, let it stand, and rub-rub-rub it off following the directions. Repeat in a couple days when after pressing my thumb against the finished surface for 30 seconds and I don’t see an oily thumbprint left behind. Great article, quite revealing. The book should be very interesting.

Do you ever put wax over the linseed oil after it dries?

Is that a good combo?

Also, I was under the impression that heating linseed oil will polymerizes the oil and convert it into a varnish?

If only it were that easy!

Hello, Bob Flexner has been a leading wood finishing authority for over 30 years. Here is an old article of his concerning wax that still stands.

https://www.finewoodworking.com/1988/06/01/demystifying-wax

I look forward to reading Steve Voight’s upcoming book, and for all areas/products/methods of wood finishing I recommend Bob Flexner’s book Understanding Wood Finishing, now in it’s 3rd edition, if I recall. It has been near my bench for over 25 years.

I just saw that to read the entire FWW article, one must download the pdf after signing up. Sorry about that if you don’t want to be on their hook.

Wax is a surface material, it lowers the friction capacity of the surface to help protect a surface finish from scuffing by filling in the invisible surface imperfections of the finish (or bare wood without a film finish). This is also what makes waxed surfaces feel good to the touch- hmmm, smooth… Works the same on the paint of your car. Most waxes can blend with linseed and tung oil, but again, the wax component will stay more topside as the oil component will penetrate the wood fibers. Wax (straight or oil blended) may give a scant help to water protection, but proper wax application and polishing (i.e. wax removal) leaves so little wax on the surface that water protection is very minimal at best. Additional coats of wax do nothing for surface protection, it simply combines with the old wax (and replaces areas of worn off wax), and then your buffing/polishing removes over 99% of what was applied- a little goes a long way. If you don’t polish it enough, the waxy surface can feel sticky and streaky. Flexner’s book goes into this really well. Wax is not a miracle product, it’s just another finishing product that you can use, or not.

Thank you sir, for sharing your insights. I’m looking forward to your book. I have been working with different finishes myself, not as deeply researched as yours, due in part to historic accuracy as a goal. You’ve stoked my fire, to keep it burning a bit longer.

This… Was far more interesting and engaging than I expected it to be. I remember you (Chris) made a comment a while back about a finishing book in the future and thinking it would be a bunch of chapters describing different commercial products and when/why/how to use them. This is far more than that, and I look forward to seeing the finished (hah!) book.

Thanks for the update!

Another +1 on waiting for the book. This is a topic that is very much of interest to me (I swear LAP somehow has a window into the books I want to read some days) but life has not afforded me the time to properly invest into the research. Best of luck on the drafting, I think it will a great one!

I look at it somewhat like our interests are being guided, but in good way.

Waiting on your book! From your excerpt it sounds like it will be an interesting read.

Have you tried Allbäck Boiled Linseed Oil? Lee Valley sells it as a cold pressed oil.

I was contemplating purchasing some to try and wondered if you had any experience with it.

Thanks, Doug

Wonderful post! Definitely improved my grasp of the subject.

See reply to Austin Davies below.

Great read, thanks for all of your work on this, Steve. You mention the Tried and True danish oil, what about their “original” and varnish oil products if you’ve worked with them? I have to go back and read your article in M&T. It’s interesting that we often think of the different products available today as “modern” creations and yet it seems we have been trying to speed up processes and make things cheaper for quite a while now. Thanks again.

Very informative. Thank you! I knew the hardware store stuff was garbage, but I didn’t know why! Did you do research on Allback Linseed oil? It may be even better than the ones you mentioned. I sell it in Canada – http://www.craftsmansupply.co, but there is probably a US dealer somewhere.

They claim it is “ cold-pressed, deslimed, filtered, sterilized, aged and boiled linseed oil.”

I’m familiar with Allbäck–the raw oil is very similar to Ottosson, the BLO is not. I have the same reservations about their claims that I have about Ottosson’s. Unless the manufacturer provides specific info about their refining–as Selder does, for example–I am skeptical. My belief is that both brands are not doing anything other than cold storing their oil (for the raw oil). In Allbäck’s case, they are adding manganese; Ottosson, I’m not sure.

This post already is beyond interesting and well into absolutely fascinating – not to mention its teaser effect for the book! Between the veils of mystery and emotive blurbs on the makers’ side, received wisdom [sic] in general and internet-fuelled mythologising in particular, choosing a finishing product so often feels like a stab in the dark. So for someone to not only pick up the mantle from Bob Flexner, but to do so and also dive deep into the traditional finishes including linseed oil is like seeing the sun come up in a blue sky after a week of solid rain! Thank you so much already for this post, and boy, oh boy, am I looking forward to your book!

Thanks Mattias, much appreciated! I very much enjoyed your post on paint a couple weeks ago.

Thanks Mattias, much appreciated! I really enjoyed your post about paint a couple weeks ago.

Did you try Selder’s linseed oil? It is a small Swedish family business

https://selderco.com/the-company/

I am only a happy amateur myself, but I am very happy with their products. No, I have no relation to them( except being a customer).

I have not tried Selder–it’s not easy to get in the US. They make a lot of interesting claims about their refining process. I have studied the patent and it seems to me that the process is basically the same as conventional alkali refining, but I’m not a chemist. If I get the opportunity, I’ll definitely try it!

Oh, yes! This is a book for me. I’m very interested in knowledge about good and safe finishing materials, so this looks promising. If I could forward a small wish? Please do not only refer to materials or products by the brand names that are familiar to American consumers! Two reasons: 1) I’m not American so I’m in the dark … 2) I’ve read my share of old ‘finishing manuals’ in different languages, and nothing dates a text faster than assuming that the present ‘nomenclature’ is permanent. I want to know what a chemist / scientist would call the stuff 🙂

I’m really looking forward to your book — it sounds like just the thing I need. Break a leg!?

Good points, and I’ll try to avoid being US-centric. The book will not be so much about products–rather, it’ll be about making (and using) finishes from raw materials.

There are at least eight or nine companies making traditional linseed oil paints in Sweden now. And some have been at it for at least a couple of decades. The thing is though, that they all have different takes on how they make their paint and what they focus on. Because it is just like Steve says in the blog post, it is more complicated than just pointing out one recipe or one method.

Dan Hansen, the owner of Wibo (who make excellent paint), states on their website that:

“A recipe for linseed oil paint is only relevant when it is written for a certain substrate based on the raw materials you have. That’s how it’s always been, and it’s therefore not possible to look up something old from e.g. 1872 and claim that this is precisely a recipe for “genuine old-fashioned linseed oil paint” – regardless of how famous the master painter who made the paint was or how well it lasted. A recipe for linseed oil paint from 1972 is at least as “authentic” if it is made by an experienced professional for a specific purpose or substrate.”

This also tells a lot about their approach to paint making.

Ottossons (who makes excellent paint) on the other hand comes from a background of making artists oil paints, and this you can see with their focus on traditional pigments and milling the paint. I at least find that their paints give a beautiful lustre that not all paints give.

Selders (who makes excellent paint) who Bengt Nordström mentions above is probalby the most innovative manufacturer. Their oils are my favourite. They refine the oil to remove everything (proteins, anti-oxidants, non hardening fatty acids etc) that does not polymerize and help preserve the wood. This makes the oil fast to dry, and gives it excellent properties for preserving wood without using any additives. Their paint is interesting in that they use modern synthetic iron oxide pigments that can be mixed with a computerized paint mixer like in a paint store. This is of course brilliant I can tell you as a working architect.

I mostly use Ottosson paint though, but have found that Selders oils are brilliant for outdoor use.

The point is that they all make “traditional paints”, but have different approaches to it. One thing that should also be remembered is that the uses that most of LAP:s readers are interested in, paint and oil for furniture, is a lot less demanding than making a long lasting coat of paint on a window or a facade.

And a last point, just like Steve says, metallic driers is nothing new. There is one Swedish company that makes an oil using a lead based drier, which they only sell to selected customers for use in an antiquarian settings where the demands on using period correct materials are extremely high.

The amount of driers in any oil from any of the Swedish quality manufacturers is so low that there is no reason to worry about it.

Correct, linseed oil paint is virtually a mono-product today; there are few options for, say, interior vs. exterior. The convenience is great and may be just what is needed for a furniture product, but if the demands are more stringent, I will be covering how to make different types.

I agree that the amount of drier in most “boiled” oils is not a significant health risk; however, that is not the same thing as saying there’s “no reason to worry” about it. There is a total lack of useful info about driers out there, and I intend to remedy that!

Great article, and I’ll be first in line to buy the book. I’ve been following everything Steve has written on this so far, and it’s fascinating.

But I don’t see myself putting in the time and effort to produce a finish the way Steve has. It’s a huge investment. I’ll follow along and revel in the discoveries (and rediscoveries). But I’m not the person who constantly looks for better finishes — or sharpening stones, or woobies, or whatever. It’s a rabbit hole that I prefer to leave to others. But I’m really, really glad Steve is doing this.

There is room for every level of skill and patience in this. Simply reading–and becoming a more knowledgeable buyer and user of finishes–is a big part of the journey. Should you decide to trying making finishes, you’ll find that some are no more difficult that nailing together 5 boards to make a box. Others are like making a drawer with slips and half blind dovetails.

Great analogy. It’s a minor task to mix oil-varnish-thinner, and a much bigger leap to washing oil and making varnish. But the becoming knowledgeable part is crucial. There are so many lies and myths about finishes. It would be great if the industry could do basic things, such as calling something an oil that has no oil in it.

Very much looking forward to this book. As a chemist, I have spent a lot of my time looking at Safety Data Sheets. I get really pissy when a company is vague on what and how much is in there. I use the power of the purse as it were and won’t buy products that shroud things. Stand oil (artist refined linseed oil) or the Tried and True products are all I use at this point. Maybe someday I will start making my own.

I simply can not wait until this book comes out! Gets into the nitty-gritty that I want and like, and the writing is clear and compelling. Steve Voigt, it was a pleasure to read this piece, and will be more so to read the book! Thank you for all your efforts!

Looking forward to the book! I’ve tried Tried & True’s varnish oil and Danish oil, but I found that both had an odd green hue. The color was very slight and only detectable when the finish was applied to a rag, but it still gave me pause. My go-to store-bought oil is now Gamblin’s refined linseed oil, which is very thin and polymerizes pretty quickly on its own. I never add driers. I occasionally refine my own linseed oil using water or ethanol (190 proof Everclear), but of course that can be a lengthy process.

Steve, based on a prior article from Donald Jusko I picked up some Cold Pressed flax oil and used a cold snap a few weeks back to do a freeze-refining. Took a few passes and learned to skip that sludge at the bottom, trust that gravity already did it’s job and there’s hardly anything usable out of it. Trouble is two things-

First storing it. I’ve got it in a quart mason jar in the basement. Working but more fragile than I’d like.

Second is cost/sourcing. What I found was online, and after refining the volume I have now cost almost double a quart of Ottoson or similar linseed oil. I would like to avoid purchasing raw substrate from Amazon, and ideally purchase locally but don’t really know where to look. A brief internet search hasn’t turned up anything local.

I don’t want to subvert or overreach in a blog post knowing that you have a book on the way but any recommendations are welcome. Very much looking forward to your work on resin and oil refinement!

Don’t buy cut-rate oil on Amazon–it’s frequently adulterated and may not work at all.

If you are willing to deal with a $100 minimum order, Jedwards virgin organic flax oil is $34/gallon, so you can buy three. A five gallon bucket is $28/gallon. If you read the fine print, it’s cold pressed, US-made. If you only want a gallon or less, Azure standard sells cold press flax oil for about $50/gallon.

I find that with careful processing, the Swedish oils lose about 1/3 during processing, whereas the fresh US oils only lose 1/4. The mucilage is easier to precipitate from the fresh oil, so a slightly lighter touch is helpful. I pretty much only use Jedwards now.

Any experience/info about Allback linseed oil?

Thanks, JDF

Please see comment above.

Hello,

I’ve used Allback organic raw and BLO for several years and have had very good experiences with it for pre-prime coats on weathered exterior wood trim. Recently, I’ve been using raw oil with a final coat of BLO before I paint wood window sash. I have also been using Allback glazing putty. I’ve also tried Shreuder enamel oil paints from Fine Paints which I like for certain applications, like doors, and metal hardware, but I am also liking Allback linseed oil paint very much on sash and trim.

I use Tried & True for all the food bowls and spoons I turn/carve. I find the finish very nice and durable, and it dries quickly enough for me. I love that the “safety” warnings essentially say “if you soak your hands in it for extended periods it may irritate you skin, and if you drink a bunch of it you may get sick to your stomach.” This is much preferable to “may cause blindness or death.”

Well now thats a turn up. After all these years I thought that BLO was exactly what it said on the tin. So I, along with many others ,have been passing along this ill-founded knowledge nodding sagely all the while. I’m horrified! Thank you Steve and LAP. I await this book with mounting interest.

I imagine you’ve come across the work of Tad Spurgeon and the idea of using salt (among many other possibilities) to refine raw oil to produce a faster drying, solvent & drier free material. I wonder if this oil painting material has wood finishing applications? Of course, “faster drying” may not be able to compete with fast drying… search “Tad Spurgeon Living Craft pdf” for the lengthy (and fascinating) pdf.

Steve is the current host, via his blog, of a couple of Tad Spurgeon’s publications, including Living Craft.

Ha, that makes sense, thanks!

Wow what fortuitous timing! I fell DEEP down this rabbit hole about 6 months ago and still haven’t found my way out. I have been experimenting with a variety of oils (tung, linseed, stand, etc), rosins, waxes (bees, candelilla, carnuba), and solvents (limonene) with two purposes in mind — to make a varnish that maximizes chatoyance and make my own (cheaper) version of a hard wax oil. I’m knee deep into the polymerization process of these compounds and can’t wait to read this book.

Steve – if I could impose – two questions for ya (if they are not otherwise addressed in your book):

What exactly is pitch?

Could I use ozone to accelerate the polymerization of tung oil?

Hi,

Pitch–Google it–not something you’ll find useful in making most finishes. Ozone–was used in the early 20th c with linseed oil. If you try it with tung, you’ll not be pleased.

Could you give us a reference to the usage of ozone and linseed oil? I have tried it and absolutely nothing happened. I used an ozone generator for several days. It was a completely unscientific experiment. Have no idea about the ozone concentration.