The Turned & Joined Chair

Production of the joined chair began as a cottage industry in the last quarter of the 18th century in Briezi and Striki (western Latvia). The start of chair making as a main source of income was likely due to the shortage of land suitable for farming. Chair making spread to other areas and it is estimated that each year a family could make 70-100 dozen (840-1200) chairs for sale in Kurzeme, Estonia and parts of Russia.

In the Home Industry section of “Woodworking in Estonia” Ants Viires wrote, “As regards chairs, the Latvian product sold at all the fairs was predominant in Estonia for many years.” He described the chair as “mostly of turned wood with a straw seat, later also a wooden seat.” The estimated annual output by Latvian craftsmen was 12,000 chairs.

As you can see, the biggest difference between the Latvian chair and many American examples are the thin back sticks instead of back slats. The seat of the chair was woven from reeds gathered from lakes near the chair making areas. The weaving was done in various patterns and usually by women. This chair is still made today both by hand and in factories.

In 1980 the BDM (Ethnographic Open-Air Museum of Latvia) asked chairmaker Eduards Tanne (born 1897) to make one of the traditional turned and joined chairs. Tanne, age 82, gamely took up the request. The video was digitized and subtitled and you can watch this wonderful craftsman make a chair, from chopping down a tree to weaving the seat, here.

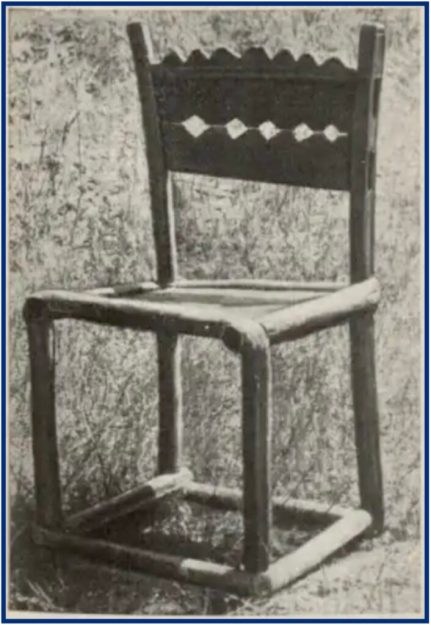

The Bentwood Chair

This is an odd duck of a chair. The first documentation of the chair was by Johann Christoph Brotze late in the 18th century. Brotze (Johans Kristofs Broce in Latvian) was German and after completing his studies arrived in Riga in 1768 to teach at the Riga Imperial Lyceum. For the next 46 years, until his death in 1823, he traveled the country documenting, drawing and painting all that he saw. His trove of everyday life is in the University of Latvia Academic Library. One page dedicated to the bentwood chair.

I can barely read Brotze’s handwriting and relied on the description of the chair in “Latvie Tautes Dzives Pieminekli” written by Saulvedis Cimermanis and published in 1969. According to Cimermanis, four pieces of ash or hazel, each no more than 5 centimeters in diameter, are used (the length of each piece is not provided). Each piece is notched where it will be bent. The ends must be carved to a conical shape so that after clamping into the appropriate notch (or bend) the end does not slip out. Brotze’s letter-sequenced diagram shows how the four bent pieces fit together. As for the bending process, we know that steam bending had long been used by coopers, wheelwrights and shipbuilders and to make sled runners. I imagine Brotze saw this bentwood chair as very unusual compared to the joined and staked chairs with which he would have been familiar. Fortunately, he not only wrote about it, he drew it.

When I first found the diagram of this chair I sent it to Chris Schwarz for his opinion. His answer was he would love to see a surviving example of a chair made in this manner. It turns out a bentwood chair from Rucava (far southwest corner of Latvia) marked with the year “1890” on the back was in the collection of the Ethnographic Open-Air Museum. This proved the chair was still being made late in the 19th century and had been made as shown in Brotze’s diagram. Chris’ response: “Oh wow. Just wow.” And, how.

We don’t know how far back this method of chair construction goes. Also, I don’t know if the chair in the photograph (Cimermanis’s book was published in 1969) is still intact. Cimermanis noted one other example of this type of chair construction and cited the work of Polish ethnographer Kazimierz Moszynski. In Volume 1 of ”Kultura Ludowa Slowian” Moszynski had a drawing of a bentwood stool that originated in west central Russia, approximately 800 miles east of Moscow.

OK, I have to add one more chair. There are thousands of brettstuhls in museums in Europe and North America. The backs often have intricate piercings and carvings and they have never appealed to me. However, I have taken a fancy to a 19th-century Latvian chicken-backed brettstuhl.

–Suzanne Ellison

Hi Suzanne,

A very interesting post indeed, first and foremost of course for its content, but to me also because of that page out of Brotze’s notebook, and your comment about the handwriting, which (as I’m sure you know) is in Kurrent aka German Cursive. This form of cursive was also widely used in Sweden up until the first half of the 19th century, and I had to learn to read it when I was studying history at university, as I used mainly 17th century sources for my thesis work.

With this in mind, I of course had to try my hand (ha!) at decoding the Brotze page (just to see if, 35 years later, I still know how) and found that the first phrase reads “Ein Stuhl, wie ihn der lettische Bauer aus Holz verfertigst, ohne daß geringste daran zu leimen oder zu nageln.” (A chair, such as Latvian farmers make it out of wood, without glueing or nailing even the least of it.)

Cheers,

Mattias

Imagine my joy finding the high-resolution scans of Brotze’s work only to be brought low by Cursive! Secretary hand is another of my foes. I had hoped one of our LAP readers could read the document. Thank you for translating the first line as it is sums up this chair: no glue and no nails, just ingenuity.

I’d be more than happy to have a go at the whole thing – I can read Cursive, and my German is, I think, sufficiently passable that I should be able to figure it out! Do you think you could send me a copy of the high-res image by e-mail? ‘twould be more convenient than peering at the screen image in the blog post …

Cheers,

Mattias

Thanks Suzanne – very interesting stuff. Chris had shown me some of this when I was out there in April. The bentwood chairs remind me of knutkorg – translated as “knot baskets”. I’ve not studied them but some friends have, Jarrod Dahl and more recently Fred Livesay. Fred and a friend of his, Jane Laurence, just spent time in Sweden studying old ones and learning how to make them. Here’s a link to a lecture they gave, maybe in preparation to their trip.

https://vesterheim.org/unraveling-the-knot-basket-investigating-scandinavian-knutkorg/

Thanks, Peter! The knutkorg looks to be another link in this craft.

Sorry for the pinterest link, I cannot find it elsewhere, here is a drawing of what looks like an archaeological find, ‘stool from novgorod’ made like that:

https://www.pinterest.ca/pin/11th-c-novgorod-stool-composed-of-4-u-shaped-part-s-of-bent-wood-that-are-linked-into-another–327848047850171703/

Thanks! If you look at a map of Russia find Kazan. Kazan is about half-way between the origin of the stool in my post and the stool from Novgorod…interesting.

Who would’ve known! Thanks to you, lots more of us get to enjoy these little gems that you kindly share on the LAP blog. Merci!

De rien! This was a fun project that took me on virtual trip through Latvia.

As for the Kurrentschrift – for anyone with the inclination (and time!) here is a quite nice guide for learning by the late Margareta Mücke: https://www.kurrent-lernen-muecke.de/lehrgang.php (third link down, in english). I will probably never get around to that study, unless I happen to live about a thousand years, considering my current “projects I’d like to do” list …

Very interesting blog entry, thanks, Suzanne. This is my attempt to decipher the writing:

Ein Stuhl, wie ihn der lettische Bauer aus Holz verfertiget, ohne das geringste daran zu leimen oder zu nageln.

Der hier vorgestellte Stuhl A ist auf folgende Art aus mehr(eren) einzel(n)en Stücken zusammen gesetzt. Das Stück a b c d bildet den Rücken und die zwei Hinterfüße. Am oberen Theil desselben sind an der inneren Seite einander gegenüber bei d und a zwei Einschnitte angebracht, um das Brett e einzuspannen. Bei b und c ist das Holz bis zur Hälfte ausgeschnitten, um es biegen und das untere Holz f g h i einspannen zu können, dessen beide Enden f und i so geschnitten sind, daß sie bei b und c einpassen und fest gehalten werden. In dieses untere Holz wird das Stück k l m n mit seinen Enden k und n , welche die Vorderfüße ausmachen, eingesetzt und das ganze endlich durch das Stück o p q r welches den Sitz giebt, so in einander gefügt, daß ein Stück das andere hält, und keines ausweichen kann. In dem Stücke o p q r wie auch l m sind vier Einschnitte nach innen gemacht, welche tief gründig herein gehen, um das Sitzbrett s zu halten. Und dergl. (dergleichen) Zusammensetzung giebt einen festen, unwandelbaren und dauerhaften Schemel.

Hope that helps

Peter

Peter, thank you! It was very kind of you to decipher Brotze’s description of the chair.

Sorry, I made some corrections after re-reading the text several times. Furthermore I inserted line breaks according to the original in order to facilitate the comparison.

Ein Stuhl, wie ihn der lettische Bauer aus Holz verfertiget, ohne das

geringste daran zu leimen oder zu nageln.

Der hier vorgestellte Stuhl A ist auf folgende Art aus mehr ein-

zelen Stücken zusammen gesetzt. Das Stück a b c d bildet den Rücken

und die zwei Hinterfüße. Am oberen Theile deßelben sind an der innern

Seite einander gegen über bei d und a zwei Einschnitte angebracht, um

das Brett e einzuspannen. Bei b und c ist das Holz bis zur Hälfte ausge-

schnitten, um es biegen und das untere Holz f g h i einspannen zu können,

deßen beiden Enden f und i so geschnitten sind, daß sie bei b und c einpas-

sen und fest gehalten werden. In dieses untere Holz wird das Stück k l

m n mit seinen Enden k u. (und) n welche die Vorderfüße ausmachen, eingesetzt

und das ganze endlich durch das Stück o p q r welches den Sitz giebt, so

in einander gefügt, daß ein Stück das andre hält, und keines aus-

weichen kann. In dem Stücke o p q r wie auch l m sind vier Einschnitte

nach innen gemacht, welche tief genu(u)g herein gehen, um das Sitz-

brett s zu halten. Und diese Zusammensetzung giebt einen festen, un-

wandelbaren und dauerhaften Schemel.

Thank you for the link! If I keep repeating “it’s just words” and I don’t faint from the effort I may be able to learn Kurrentschrift.

Apologies! I was reading the comments on my phone, and didn’t scroll far enough down before replying above to see that Peter-Christian had already deciphered the Cursive for you …

Cheers,

Mattias

I was fortunate enough to visit the Ethnographic Open-Air Museum of Latvia 40 years ago on a trip to Latvia. It is well worth your time to visit if you ever get the chance.

It is on my list (which grows with each research project).

That bentwood style of joining is used on some antique Chinese chairs.

Some I’ve seen might be dated to 150 years or so old, others have been listed as “Ming Dynasty Style” not that that really narrows things down date wise.

I think I’ve also seen Chinese bamboo furniture bent and joined similarly.

This would be furniture made from woods like Elm rather than the fancier huanghuali wood that was used for more prestigious furniture.

I presume the wood joining techniques might have migrated along whatever migration route it is that goes from Urumqi in what is now one of the Chinese Autonomous Regions in Northwest China, to Northwest Scandinavia, since some of the ancient Urumqi ceramic sculptures show people on camels wearing dress similar to archaic Scandinavian garb that was worn in some areas recently enough that I’ve run into old photos showing people wearing similar clothing.

Damn Bolsheviks! I love watching movies about old craftsmen. It makes me pine for the olden days. But without the Bolsheviks. I’m going to have to try making one of those bentwood stools.

Fascinating.

First glance at the bentwood chair reminded me of those outdoor chairs made of pvc.

I’ve seen chairs with bent bamboo done in that way in the Dominican Republic.