The first section of my forthcoming book, “Backwoods Chairs,” documents my search for the dwindling ranks of Appalachian woven-bottom chairmakers who count(ed) chairmaking as a significant income. The income piece is essentially my only criteria for the makers: that chairmaking provides at least a part of their livelihood. I had no real idea what to expect when I started my search for ladderback chairmakers. Try as I might to dislodge the romantic vision of a mountain maker working wood on a secluded front porch of a cabin, that stereotype lingered in my brain as I started the search. At times, I found a maker shaving wood parts on the porch. Other times, the idyllic vision was incomplete – as when I visited a maker shaving parts next to a generator, which powered the lunchbox planer used to thickness his chair slats.

Appalachian post-and-rung chairmaking is far more complex than I initially imagined. For starters, the makers do not fit into simple categories. Some make all their income through chairmaking, and others a portion of it. Some do it seasonally, either working around their farm’s growing season or working in the shop during the summer months. One person did not consider himself a “chairmaker” at all, though chairmaking has been a constant in his life for five decades. The whole thing is squishy.

I also recommend readers put aside any tidy categories when considering the makers. The lines between “amateur” and “professional” blur to the point that they are no longer relevant. I found “part-time” and “full-time” categories to be pointless as well. At the end of the day, there are either chairs or no chairs.*

I sought out makers of the basic post-and-rung form, though each maker creates distinctly different work. I think of it this way: Chester Cornett could only make a Cornett chair, and Brian Boggs could only make a Boggs chair (I know, that statement is so simple that it’s stupid). The chair is a reflection of the maker; the maker DNA is right there for all to see. The Cornett chair reveals the use of the knife, and Chester measured everything by his hands and thumbs. His approach helps create that magic in his work, and it’s a constant across his career, from his beautiful common chairs as a younger man to his bombastic late-career rockers.

Boggs’ chairs are refined and highly engineered. There is intention behind each detail, both in the design and the technique. Boggs’ ladderback chair was reimagined into a modern piece in his Berea Chair until it could not be improved upon. Brian took a form typically considered rustic and backwoods and reimagined it for a contemporary setting. He did that by making a chair with equal consideration toward comfort, technique and design. Cornett and Boggs – two chairmakers beginning at the same post-and-rung starting point, yet yielding wonderfully different results.

Whenever possible, I traveled to meet, interview and photograph the makers. I wanted the opportunity to explain by book in person and figured this was my best approach to record and reflect on the makers in the fullest light. The initial interview and meeting proved helpful, especially for photography, but the follow-up proved most fruitful. The makers could size me up and determine if they wanted to provide more to this project. One maker showed me the door after 20 minutes. That bruised my ego a little (was it something I said?) but most followed up by sending pictures and sharing additional stories and techniques. Like James Cooper, most wanted me to get this right. That meant educating me on all things chairmaking.

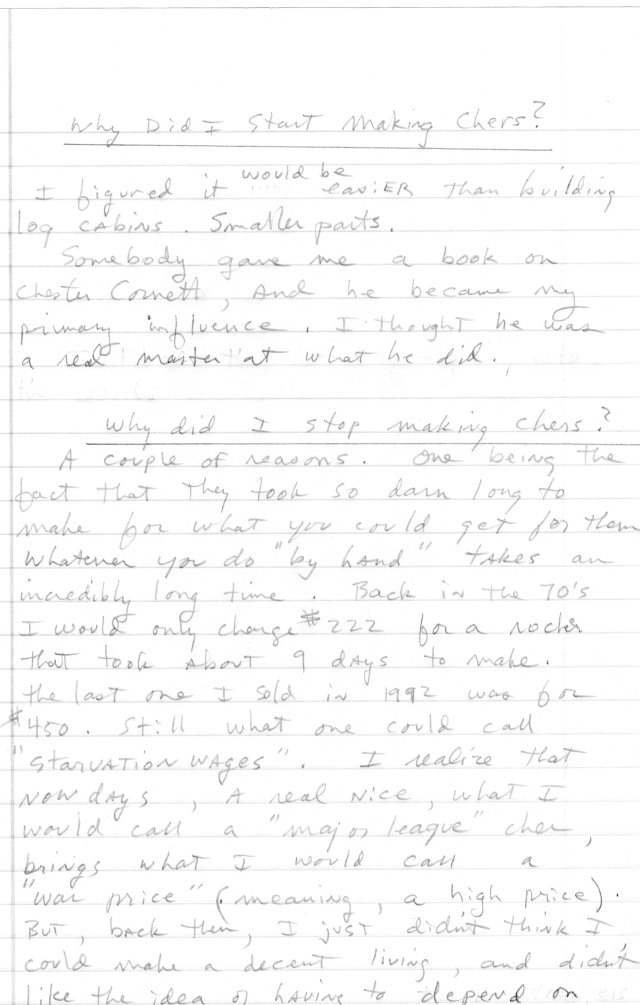

I met Cooper of Jackson County, Ky., earlier this year. We sat on his porch during an early spring downpour and discussed his approach to chairmaking. James crafted handmade chairs as his primary income source for three years in the late 1970s and early 1980s then decided to make a career change. He followed up our initial conversation by sending 10 pages of written notes and a collection of his early photography. With it, he opened my eyes to his reality of making chairs in Eastern Kentucky.

The notes are shared here with his permission.

– Andy Glenn

* A note about categories. I request that the reader does not overlay “morality” onto the chairmaker’s decisions (as in, one decision is morally superior to another). There is a tendency within woodworking circles to philosophically judge the work of others, where handwork can be judged of more value than machine approaches (and this, being a Lost Art Press publication, will likely reach those who appreciate handwork). I propose that an outsider has no say in the decisions of the maker. Decisions are purely personal choices made by the chairmaker.

One example: the chairmakers I met in the process of the book made the following decisions regarding their chair rungs; 1) split and shaved 2) turned from lumber 3) store-bought dowels 4) made on a dowel machine 5) handheld power planer to shape and taper them after using a brace to cut the tenon on the end. One choice is not philosophically superior than another – at least as far as an outsider can judge.

My goal is finding out why the maker decided upon an approach or technique. Is it because they work within an established tradition? Is it for speed and efficiency? Is their design target “old-timeyness” (which deserve the shaved rungs)? Regardless of the answer to those questions, I recommend the “handwork is more pure than machines” belief be suppressed when considering the work of others. Only the chairmaker gets to make that “moral” decision about their work.

Awesome article. So cool seeing the handwritten notes. True history. Another book I’m gonna have to add to the collection…!

James Coopers notes here are very special thanks for including

Now, I found this a fascinating blog and I would love to buy a copy of this book, when it comes out. I assume you will have Russ Filbeck in there. Anyone not in the USA? Best wishes, Mike

Hi Mike, I’ve focused primarily on p&r makers within central Appalachia. Some makers reside outside the region, but there’s a line that connects them back if so. Thanks for suggesting Russ.

There’s a lot of gold in Mr. Copper’s words (and Andy’s). “Slotches” is possibly my favorite neologism. Really looking forward to to reading the entirety of Andy’s findings.

Thank you, Travis.

“Sygogglin” is a good word. It doesn’t have the pedigree of words like “spelch,” but we can fix that…

I had never heard of sigogglin before. You really do learn something new every day.

Very interesting read !

Andy Glenn on grading chairs:

“So, a chair can be … ‘good enough for the government’ …”

Hehehe!

‘good enough for the gov’t’ – not my words (though I wish)…..those come from James

“Good enough for the government” or a similar phrase was in common use in Maryland in the 1960’s. My father would use it to describe something he made or did which was adequate but nor particularly good.

“My goal is finding out why the maker decided upon an approach or technique.” For me understanding the why is at least as important as the what and the how. Unlike Peter Follansbee in his study of 17th century furniture, Andy has the opportunity to learn directly from the makers.

In a previous article about the book Andy said he isn’t a folklorist. Perhaps he doesn’t have the academic qualifications or position as a folklorist but his approach of putting aside tidy categories and not making moral judgements reflects the best type of folklore study. This is another example where “the lines between “amateur” and “professional” blur to the point that they are no longer relevant.”

Very kind, David. I hope the finished work does the whole thing justice.

Really looking forward to this Andy!

Thanks Sam.

Just finished making a hickory bark/ash stool with Andy at Pinegrove. Can’t wait to read the book and try and make a few more.

Thanks Dale.

Chairmakers and writers have a lot in common. Lots of hours, little pay. I’ll bet Andy makes about ten cents an hour if he truly added up all the hours that go into this. And he’d be the last to complain about it. Love is like that.

I’ll be first in line for this book when it’s ready.

Thank you, John. My mental trick here is ignorance….not counting the hours. It’s an enjoyable project, that’s for sure.

I have an old post and rung chair that belonged to my great-great grandmother who lived in middle Tennessee near the Kentucky border. It may not be rougher than a cobb, but it is definitely rough. The flat on the front of one post has drawknife or spokeshave chatter the whole way up and one of the rungs was definitely scrap from another project because it is sawn halfway through near one end. I don’t know what the original seat was, but my grandmother had it recaned back in the 90s by a blind gentleman who caned seats. It may be old and rough, but it is comfortable and I sit in it many hours every week and it has a spot of prominence in my shop.

Can we contact you if we know of some others? There’s one family really famous in my area of Southwest Virginia.

Sure. Always interested.

yeah give me more!

I like where you are heading with this book. My two cents worth: categorization leads to standardization, standardization leads to measurability, measurability leads to defining worth or value, defining worth or value based on a measure leads to exclusivity. I have a chair built by my great-grandfather around the early 1900’s. It is a ladder back design with both hewn and turned elements with a stretched calfskin seat. It was built with what skills he had, the materials he had available, and with design and function of what he thought “looked good and would work”. It is “rough as a cob” and categorizing all the choices he made and techniques he used to build it would greatly de-value the chair to primitive furniture and of little monetary value. It is not a fine piece of American furniture. But, to someone who does not have a chair it is a masterpiece of fine craftsmanship, beautiful design, and upmost functionality, and therefore as valuable as the throne of a king. Knowing the why is just as important as the how. It gives back value (whether real, moral, or philosophical) to the item that the how may have taken away.

The two things my dad told to never forget ,is experience and knowledge for without one you will never learn . If you have the knowledge then you will gain the experience how you gain both is by reading or watching someone completing a task the way they were taught or learned . To me the old ways that were taught to me gave me the foundation for how I do my woodworking, and yes I have found better ways to do things that were taught to me .so now I am teaching them to my up coming generation. When I first started out most of my projects were “rough as a cobb” but with experience they have generated to the level of good craftsmanship I am sure that when mr. Cooper and mr. Glenn started out they had pieces that did not look like what they make today there is a vast amount of knowledge in the handwritten notes as well as experience to pass down . am looking forward reading more.

Mike angel in London my?

A chairmaker in Tennessee who is still alive is Tim Hintz …

Be Safe

Joe

What fantastic views, reminiscences and comment, sat in England on a cool winters day this lifts my spirits! I was taught the rudiments of chair making by Bob Wearing (who Lost Arts has championed) on Saturday mornings in his school workshop using Fred Lamberts rounders and a turning engine made from a motor driving a car gearbox on a stand, gearstick and all! Chairs are cool.