Some of you will recall that I began work on “The Anarchist’s Finishing Manual” a few years ago, then abandoned it. Dropped it like a hot turd I did.

I’m sure that some of you think that “Big Poly” fingered me. Or I’d huffed too many VOCs (volatile organic compounds) to do the job. Here’s the real story.

For about two years, I read a lot of scientific papers and (for practical perspective) safety manuals for art schools that use finishing materials. Plus, I had many conversations with a dear friend who has devoted her life to this sort of industrial hygiene. And then I came to a conclusion.

I am not the guy to write this book. And, in fact, it might not be a book that is urgently needed for this audience.

Most of the people who read my stuff are devoted amateurs or run a woodworking business on the side. Few of my readers are professional finishers or professional woodworkers who use a lot of exotic finishing materials. Because of this, most of you are unlikely to encounter enough dangerous solvents and heavy metals to be terribly concerned.

If you simply follow the safety instructions on the can, work in a well-ventilated area (that’s key!) and aren’t finishing 10 hours a day or week, the risks are low.

Despite everything I’ve just written above, however, I still advocate that people reduce or eliminate as many VOCs and heavy metals from their shop as possible. And that is why I am posting this blog entry today.

The following manifesto – for lack of a better word – was the starting point for my aborted book. It’s how I feel about finishing. I don’t much use the word “feel.” I prefer the words “think” and “force poop.” My feelings are based on decades of living with finishing materials.

I started with spray finishing when I was about 19, but I am not an expert finisher. But I have worked with people who take finishing seriously, especially Bob Flexner and Steve Shanesy, both with Popular Woodworking Magazine. My take on the craft of finishing is different than theirs. They both came from the world of professional finishing and refinishing, where durability and surface perfection are important. As you’ll see, I live in a different quadrant.

In the end, I decided to put this opinion piece out for public consumption because I think it is the minority view. But I think it is valid, and so I’ll take my licks and continue to listen, experiment and try to become a better finisher.

And live a long damn time.

Finishing for the Long %^&%$#@ Haul

When I talk about finishes with customers and fellow woodworkers, most are concerned about impenetrable, absolute durability. That is, how much toddler can the varnish on this table take? One toddler? Perhaps 2.3 toddlers?

I’ve always struggled when having this conversation because my opinions are upside down compared to most commercial shops, factories and (sometimes) home woodworkers. They favor polyurethane, lacquers and other hard film finishes as the armor against the army of the babies, the platoon of hot pots and the rivers of fingernail polish remover and spilled chardonnay.

Me, I prefer finishes that can be easily repaired, that look better with some miles on them and (here’s the downside) require routine maintenance and care.

I dislike finishes that form a seeming impenetrable surface film. Why? When these “highly durable” film finishes fail under duress, they tend to fail spectacularly with ugly chipping, crazing and scuffs. And repairing these durable film finishes can be difficult or impossible. Sometimes you have to remove the stuff (a health hazard), re-sand (a lung hazard) and reapply another finish (another opportunity to bathe in VOCs).

Put another way, using “durable” lacquers, varnishes and polyurethanes is like buying cheap clothing. It looks great for a while, but in a few years, it won’t be good enough for even a Goodwill donation.

So, when I choose a finish, I ignore the industry-standard scratch and adhesion tests. Instead, I separate finishes into two buckets:

- Finishes that look incredible immediately but look like crap in 20 years (the short-run finishes) vs. finishes that look incredible when worn/abused (the long-run finishes).

- Finishes that want me dead vs. finishes that I can apply while buck naked.

If you like math stuff, you could create an X-Y axis with four quadrants and place every finish into one of the quadrants. Perhaps I’ll do this. Or maybe it’s best if you do some of the work yourself as you ponder your favorite finishes. For now, let’s talk about what each of these categories means.

Finishes That Look Fantastic Immediately (Short-run Finishes)

My first woodworking job was at a factory that made high-end exterior doors. While part of my job was to cut rails and stiles, most of the time I worked in the finish room. Our goal was to make doors that looked great on the showroom floor and could endure the indignities of sun, rain and snow.

So, we used lots of pigments and glazes to color the wood. Plus, lots of two-part high-tech film finishes to protect the color and wood below. This finish was so nasty you couldn’t even go into the automated spray booth without a protective suit on. (What exactly was the finish? They wouldn’t say.)

But when the finished doors came out of the booth, they were stunning. Though I didn’t own a house at the time, I wanted one of these doors.

I think it’s fair to say that a spectacular finish is one of the two key ways to impress a customer (the form of the piece is the other). Customers aren’t (in general) a good judge of joinery or wood selection. But they do know smooth and shiny – thanks to plastics.

As a result, most people prefer finishes that offer the feedback of a Tupperware bowl. And commercial shops prefer finishes that are fast to apply. Combine both properties – smooth and easy – and you have a winning commercial product.

Lacquers, shellac and varnishes (including polyurethanes) all offer that plastic feel with minimal effort in the workshop, thanks to spray equipment and solvents that make them easy to apply. These finishes are, in general, quite durable in the short run. They are not likely to scratch or scuff – at first. Most are water-, heat- or alcohol-resistant – at first. And they offer low maintenance – until they cross a magic tipping point where they fail and become super ugly.

There is, of course, also the question of what the piece of furniture is used for. If you use these short-run finishes on a picture frame, an honored cabinet or decorative object that rarely gets touched, it will likely look good in 100 years if it lives in a climate-controlled environment. This is true no matter what finish you use.

So, it’s easy to see why many woodworkers prefer these short-run finishes. Heck, I loved them for many years. They look great immediately (everyone’s happy), they are fairly easy to apply (the woodworker is happy) and they take a beating for a decent amount of time.

And to be 100-percent fair, there are times when I use these short-run finishes, too. Some pieces are reproductions and need a shellac finish to be true to the original. Sometimes a customer insists on a lacquer or polyurethane – even after I explain the downsides. I’m in no way a purist. (Purity is for soap and lucky bastards with trust funds.)

Some finishes that look fantastic immediately:

• Shellac

• Lacquers of all sorts

• Varnishes of all sorts (wiping, spar, brushing etc.)

• Polyurethane (it’s also a varnish, but most people don’t know that)

• Danish oils that contain varnish

• Water-based film finishes, such as water-based lacquer and “poly” (a misnomer, but whatever)

• All-in-one stain and finish products (actually, I don’t know if these ever look “fantastic”)

• Acrylic paint

• Oil-based paint

Finishes That Look Fantastic in 20 Years (Long-run Finishes)

If you love antique furniture, you probably prize patina – the gentle wear and tear that a loved object develops after years of use. I think of patina as a combination of natural oils (from you, plants and other animals), grime, wax, paint, UV, scrubbing, scratching and burnishing.

Some finishes are ideal for building patina. Oils, waxes and soap are all finishes that tend to accumulate patina rapidly because they offer little or no protection from the real world. Interestingly, I find these finishes can be less impressive when first applied (though some people love them). For example, a soap finish on a beech chair looks like a beech chair that doesn’t have any finish on it – perhaps a little bleached. An oil finish doesn’t develop any real sheen until you apply lots of coats, such as with a gunstock finish. And wax finishes fade quickly and can get worn away.

If you want these basic non-film finishes to look great, you need to put in the hours. That means more work and more coats as you apply the finish to achieve an initial “wow” response, plus more hours of maintenance with high-wear items, such as dining tables.

But if you stick with the program, reapply a yearly coat and stay away from the dip tank and spray booth, you will end up with furniture that is as inexplicably beautiful as a weathered face.

Finishes designed to look better with age (after years of maintenance) can be difficult to sell to a spouse or customer. And that’s why our family’s dining table is covered in pre-catalyzed lacquer and – after only 10 years – is a mess of ugly flakes and crazes. The wood’s figure is almost completely obscured by the deteriorated finish.

Yes, I hate myself for this.

Finishes that look fantastic in the long run:

• Oils of all sorts (linseed, tung, walnut and other true oils that don’t contain varnish)

• Waxes of all sorts

• Oil and wax blends

• Soap

• Milk paint (be aware that a “milk” paint can be an acrylic paint)

• Paints

• Scrubbed finishes – bleach, lye and soap

Sidebar: Paint Covers Everything

One of the interesting exceptions to this taxonomy is paint. Paint can fit into every category, but that’s because there are so many different kinds of paint. It can look stunning when first applied, such as an automotive finish, then look bad when it fails. Or it can look great in 20 years, such as a real milk paint finish or a homemade linseed oil paint.

Likewise, paint can be safe enough to eat – you can make it from raw linseed oil (or eggs) plus a little dirt and beeswax. Or it can wreck your body when it’s loaded with lead.

Because we can’t make many blanket statements about paint, we’re going to need some adjectives when we talk about this finish. Latex (aka emulsion) paint is a different animal than casein paint (usually called milk paint). Oil paint is different than powder coating. Each paint has its own risks and rewards, so we’ll take a closer look at paints later in the book. (Haha, no we won’t.)

Finishes That Want You Dead or Sick – or at Least Irritated

The truth is that most of the cured finishes on the furniture in your house are inert and mostly harmless. The resins, waxes and oils in the finishes are derived from natural ingredients – wood, flaxseed, beeswax – and would do little harm if you ingested them.

The problem, then, is the solvents and additives – the chemicals that allow the finish material to flow, to be applied to the wood and to assist the finish in drying quickly and beautifully. Solvents can be mostly harmless (water) or frightening (benzene, xylene or toluene). When I consider how “safe” a finish is, I’m mostly worried about the solvents and drying agents.

Let’s take linseed oil as an example. It’s derived from the harmless flax plant, and you can buy it at the grocery store to use in salads, soups and dips. It’s not going to hurt you. In fact, it might be healthy. But when you buy linseed oil at the home center, it can be a different story.

“Boiled linseed oil” is not simply flaxseed oil that has been heated so it will dry in a reasonable amount of time. (If it were, that would be nice.) Instead, boiled linseed oil has been doctored with heavy-metal drying agents (such as cobalt manganese salt) so the oil is convenient for woodworking or painting. The drying agents turn this grocery store item into something that can make you feel sick if you breathe in too much.

Added to that is the problem that most people thin linseed oil with mineral spirits (paint thinner) to make it easier to wipe on than Mrs. Butterworth’s pancake syrup. Mineral spirits are distilled from petroleum and contain forms of benzene, which has been shown to cause cancer in animals. Mineral spirits are also an irritant to your eyes, ears and respiratory system. So even stuff that seems natural and harmless isn’t necessarily so. You have to dig a little deeper.

In the shop, my goal is to use finishes that won’t make me sick or shorten my life. That might seem like an easy task. The problem is that most off-the-rack commercial finishes are at least a little poisonous.

I wish I could list every brand of every finish here and rank them from mostly harmless to a HAZMAT. Unfortunately, finish formulas change, environmental laws change (for the better and for worse) and commercial brands come and go. When you consider buying a finish that is new to you, my advice is to look up its Material Safety Data Sheet (MSDS), sometimes called the Safety Data Sheet (SDS). These are available from the finish manufacturer and are widely published on the Internet.

Read them over and keep in mind that it’s the finish manufacturer that fills these forms out. (In other words, it’s like reading the side effects of prescription medicine). If the MSDS doesn’t scare the living crap out of you, it might be worth a go.

Oh, and there are a lot of finishes that are flammable. You’ll find that out on the safety data sheets, too. That’s also bad.

Finishes that want you dead, sick or at least irritated:

• Shellac with methanol

• Solvent-based lacquer (especially catalyzed and pre-catalyzed lacquers)

• Polyurethane and varnish thinned with mineral spirits

• Oils treated with heavy-metal drying agents

• Cyanoacrylate (super-glue) finishes

• Finishes thinned with turpentine

Finishes I Can Apply Buck Naked

I wish this were a huge category of finishes for you to explore. It’s not. Many waxes have harmful solvents. Most oils contain some heavy-metal driers. So, I have to say that most of the safe finishes are ones you make yourself. Or they are finishes that are basically raw ingredients that get applied with cleverness.

There are some manufacturers that specialize in making finishes without VOCs or other harmful ingredients. I have experience with finishes from Tried & True and Sage Restoration, though I am sure there are other manufacturers out there (or, I hope there are). The bottom line is that when searching for any finish, it’s always eye-opening to read the safety data sheet (the MSDS or SDS). Just because a label says the finish is “all natural” doesn’t mean it’s safe. Venomous spiders are all-fricking natural as well.

I’m going to be honest and say that most of the finishes in this category require a little more skill or effort to apply. They all require maintenance (if the finished object is regularly handled). And they might not be the always-shiny finish that reflects every sunbeam.

But I still love these finishes.

Many of them are rooted deep in our history and have been largely forgotten. One of my favorite finishes in this category is a pure beeswax finish applied with a “polissoir.” A polissoir is a stiff bundle of abrasive sticks – usually rush or broom corn – that is used to burnish the wooden surface with some beeswax until it is impossibly tactile and lustrous.

The downside? It’s a lot of work to burnish a large object with what is basically a bit of a broom. If you did this in a high-volume commercial shop, two things would happen. First, you’d go out of business because finishing a table this way would take a day or more. (But your pecs would look awesome.) Second, your one customer would complain the first time he or she abused the table with heat or alcohol. It’s a finish for a special type of customer (usually yourself).

Other safe finishes have yet to leap a cultural barrier. In many places in Europe, furniture and floors are regularly finished with plain old soap. Yes, the same thing you use in the shower (minus the detergents etc.). It’s a great finish for light-colored woods. But soap requires regular maintenance and doesn’t offer any significant protection.

Me, I think these finishes are worth the effort. We live in a world where everything has been formulated – processed foods to target a sweet tooth and plastics to surround us with slick smoothness. Heck, some casinos even pump their halls full of chemical smells to mask the harmful tobacco smoke and trick your brain into doing something really stupid in Las Vegas. With a donkey.

Your furniture shouldn’t be like that. It’s made from trees. It’s built with your hands. Why should we slather it at the end with synthetic chemicals that harm us? Because let’s be honest: It’s the woodworker who bears the brunt of the VOCs and heavy-metal driers. By the time the project gets to the customer, most of the harmful stuff has evaporated.

There’s one other benefit to these finishes that might not be obvious. Many woodworkers are worried about the future of the craft. As the older generation dies out, it’s uncertain if there will be younger woodworkers out there to replace them. By using safer finishes, you’ll do something to extend the craft – you’ll live longer.

Finishes you can apply buck naked:

• Natural waxes without VOCs

• Natural oils without driers or solvents

• Soap

• Oil and wax formulas (without VOCs)

• Casein paint (aka milk paint)

• Linseed oil paint (without VOCs or driers)

• Any paint that is a natural oil with safe pigments (yes, there are both safe and unsafe pigments) plus a dab of beeswax

• Some water-based finishes (check the safety data sheets)

• Shellac dissolved in ethanol (though some of you will debate me)

Most of All, Be Reasonable

I won’t lie to you, I use finishes from all four quadrants. I make a lot of different pieces of furniture for customers who have their own set of desires when it comes to a finish. I think that’s OK – it’s the woodworker who bears the brunt of the VOCs.

So, it’s up to you to know the risks of applying a finish. You need to buy – and use – the right protective gear. Avoid shortcuts. And if you ever start to feel intoxicated while finishing, know you are doing something wrong.

Also know there are always ways to make a particular finish less toxic. Substitute ethanol for methanol. Use odorless mineral spirits instead of turpentine or regular mineral spirits. Use stand oil (pure linseed oil without metallic driers) instead of boiled linseed oil.

Most of all, however, you can make your life a lot less chemical and volatile by simply opening your mind to different ways of working. A good oil-and-wax finish is easy to apply, is incredibly tactile and can be practically non-toxic. Try soap. Make your own paint. And always read the safety data sheets for the stuff in your shop. Though the safety sheets can be confusing and difficult to interpret, it’s pretty easy to determine if a finish is scary or drinkable.

My goal is build things that endure, and that allow me to endure as well. I know too many woodworkers whose bodies have been wrecked by the heavy lifting and the chemicals of our craft. I know too many who have had scares with unusual cancers. And I’m haunted by stories of fellow woodworkers who dropped dead suddenly.

I don’t want to be that person. I want to die at a very old age, in a bed I made that is finished with an oil and wax I cooked up myself.

If you have the same sort of urge, these ideas are where to begin.

— Christopher Schwarz

Great content Christopher. This is the type of information that when consumed and applied will make someone a more informed and educated woodworker. No fluff, full of substance and lots of personal opinion. That’s what transforms knowledge into wisdom and anytime someone shares the reasons why they do or don’t do a particular thing it turns that knowledge into usable wisdom. And it’s nice to know that I’m not the only one who likes to apply finishes in my shop well being buck naked.

I live in Canada. Buck naked finishing is seasonal, up here.

Hard to get high-proof ethanol though. The reasons might be related…

Build a still and make your own…. 😉😎

“They favor polyurethane, lacquers and other hard film finishes as the armor against the army of the babies, the platoon of hot pots and the rivers of fingernail polish remover and spilled chardonnay.”

I feel targeted!

In all seriousness, I did a big blog post comparing lacquer, urethane, shellac, Odies Oil, and Rubio Monocoat.

My criteria were the immediate resistance to alcohol, water, nail polish remover, and ketchup. Shellac actually held up fairly well, but the two hard oil finishes failed miserably.

In my own home, I might be able to work with having to refinish a spot every time my kids leave a glass on something overnight. But I know my customers would balk at it.

I think the technology will get there, to where a zero VOC can performs well as a film building finish in terms of a business-to-consumer sales setting. But it’s just not quite there.

And, in case it seems I missed the point of the article…. I don’t wholly disagree with you. I definitely prefer the patina of a natural oil, soap, or wax (it’s what I use exclusively on my reproduction work). I just do a LOT of coffee tables and dining tables too, so that colors my opinion

Thoroughly enjoyed your article, Chris. Thank you. I wonder if there are natural options for an exterior piece (like a deck chair or a mailbox on a covered porch) or if one must then bow to the alter of the VOC to get any sort of longevity.

Linseed oil is a great exterior finish – if you reapply regularly. Paint and deck stain are excellent exterior finishes (as they block UV)..

So, basically, stick with Christian Becksvoort’s formula. I think he knows what he’s doing.

What is that?

If you plonk this post as a PDF (I can do it for you and send it to LAP), that’s the ‘Anarchist Finishes Pamphlet’ we all have been waiting for.

In the greater realm of woodworking, there is more misinformation and myths surrounding finishing than anything else. It’s generally a third rail that I don’t care to go anywhere near. You’re brave for even bringing it up.

I’m generally easy to please. I find something that gets the right result, first and foremost. Then I try to do it safely, with the least effort and expense. This is true for finishing, sharpening, tools, technology, and even the food I eat. I only experiment until I arrive at a satisfying result.

I anticipate arguing with people over finishing and sharpening with the same eagerness as politics and religion — none at all.

We know there’s not a LAP legal department because this post didn’t contain a warning about spontaneous combustion of one’s hairy bits due to inappropriate use of drying oils while naked.

Well damn, this is super helpful and a bit shocking. After years of successfully finishing with what I thought was an all natural tung oil from the hardware store (joke was on me, it’s mostly varnish) I then went to using multiple coats of a pure tung oil, which seemed to have the permanent consistency of my old lava lamp. So I switched to Danish Oil and have liked the results, and ease of application until I followed Chris’s advice and looked up the Material Data Safety Sheet:

Chemical Name

Mineral Spirits

aromatic petroleum distillates

Dipropylene Glycol Monomethyl Ether34590-94-8 5.0 Stoddard Solvent

Well now that’s embarrassing as I am a professional environmentalist. I didn’t even always wear gloves when I applied that stuff.

I am grateful to you Chris for providing this proverbial two by four to my noggin this morning.

Thanks.

John

I used Heritage Natural Finish on the trim and beams of my shop. It Is linseed oil, tung oil, rosin, beeswax, and citrus solvent. It is touted as safer than most. The linseed oil has been “pre-aged”, presumably with heat. It states no metallic dryers. It smells like oranges for a few days. It dries hard over a period of weeks. It is a bit expensive. I think it is the same formula as Land Ark.

Well researched and extremely helpful. Many thanks for sharing this information.

Ever use Gilsonite paint? The real stuff, not just the color? It was mined near me originally. Always wanted to try it on something.

Sort of. In the 1990s we used it to create a brown stain to match some old English pieces we had to color-match. But I’ve not investigated it beyond that. Sorry.

This is an interesting topic to me. I have been woodworking for 30 years. I used to be able to use the most toxic of products no problem. In my 20s, various chemicals could get on my hands and at most my hands would feel dry. However, as I have gotten older I think I have built up toxicities or intolerances. Products I used to use like briwax now almost immediately give me a headache, dry itchy eyes, nausea, and if it gets on my skin my skin gets super dry, cracky and will look like leather/alligator skin for several days.

So i have been looking into safer Finishes. The current one I am using on some wall cabinets is home made truly boiled linseed oil mixed with beeswax. I followed a wood by wright video and it was easier than i thought. I need to look into other more options as well.

The original briwax used toluene – a rather nasty solvent. The new “Toluene Free” briwax has substituted Xylene and Naptha for the Toluene. An improvement maybe but not something that I’d want to use. Chris didn’t mention it, but his daughter Katie (?) makes a nice wax out of some special turpentine and beeswax. The formula was published by Chris.

This should have been a book. I’d buy it in a heartbeat

very interesting. What do you think of Becksvoorts Tried & True Boiled Linseed Oil plus Epifanes spar varnish mix? I gather he thinks it’s repairable

Never used either. I don’t know how varnish would be easily repairable without sanding it down and reapplying — it’s not like shellac or lacquer where you can dissolve the coats below.

yes, the repairability makes little sense on the face of it to me. But I know an infinite amount less than Becksvoort…

Oil/varnish blends are deemed to be repairable because usually you apply so little resin that almost none cures on top of the wood. Some of the pores will be partially filled cured resin, but the surface has so little that a scuff sand and recoat will make it look like new. If you build a bunch of coats of any oil/varnish blend (any of the homebrew maloof type finishes are in this category) then it can’t be repaired.

Several years ago I discovered hemp oil. Having a basement shop, the need for no VOCs and ventilation is key. Hemp oil looks great if you’re going for the old age look on your furniture and it smells like crushed walnuts. Great stuff!

1:1:1 shop finish and wax over shellac sometimes just wax sometimes nothing at all.

Thanks Kris. That was a wonderful article. I love your writing. And content.

Wasn’t there a period finishing guide being published under the LAP label by a different author? Did I space and miss the release, or has that one gotten held up for one reason or another?

Don Williams is working on a book on period finishes.

Really looking forward to this book! I don’t even do period work, but I enjoy Don’s writing style and I’m sure a will learn a lot. P.S. This was a very valuable post, being an idiot I didn’t notice that Boiled Linseed Oil had VOCs! Is there anyone who sells Polymerized Linseed Oil?

Art supply stores sell “stand oil” which has no driers but will polymerize.

Yes, Tried and True sells exactly that (calling it Danish Oil):

https://www.triedandtruewoodfinish.com/products/danish-oil/

“…penetrating linseed oil finish that is polymerized for fast and easy application on interior woodwork and furniture.”

There are innumerable posts out there about their products, including the very specific application requirements. I can say that I live in a cool, humid area and haven’t had any trouble.

Andy, when I click on the link in your comment, I get a site called GoMedia.com. I don’t know what it is, but it isn’t Tried And True. Probably it’s OK, but anybody else interested in the product, make sure your malware protection is up to date.

Strange. That’s the correct URL, but feel free to simple Google it if interested: Tried and True Danish Oil.

Great write-up. What’s your preferred finish for tool handles? I recently refurbished an old backsaw and used paste wax as a handle finish. It feels nice, but after only a few uses seems to be sucking in the grime and oils from my hand, as evidenced by the significant discoloration.

I did several new birch backsaw handles with two coats of BLO, let dry for a week, one coat of 2 lb cut shellac then 2 or 3 coats of paste wax. They feel nice, not plastic or slippery.

The oil and shellac help to keep grime off. I can clean them off with a rub of fresh wax or polish. For wax I used a 1:4 beeswax and turpentine.

They look lightly used now, a few years later, but not in a bad way. I didn’t get this from any reliable source, just used the stuff I had in the shop. Your mileage may vary.

Very good post! I know you have scrapped the idea of a full blown book on the subject, but maybe an actual booklet that could perhaps be part of series on other technical aspects of woodworking, would be of interest to many and be a good seller?

Good reminder of similar comments you wrote in the anarchist design book. Timely as I am working on a kitchen island top.

Thanks for an interesting and thought provoking post. One suggestion would be about gloves. When chemists handle any solvent other than water, they are required to wear disposable gloves. Nitrile gloves are “usually” better than latex gloves, which “usually” are better than vinyl ones. There are solvent by solvent exceptions to those rules, but in general, they hold up pretty well. A MSDS/SDS will sometimes specify what kind of gloves to use for that material. Pre-COVID-19 it was easy to get any kind of glove from either a drug store or the home center. Now it is a little harder. In general though, you want to try and keep any kind of solvent off of your skin so that it can’t be absorbed into your bloodstream. If the glove gets doused in solvent or a stain with solvent, take it off right away and put on a new one.

We use nitrile gloves when handling any VOC. Should have mentioned that.

When you do use a VOC solvent, do you have a preference? I’ve been using 100% d-Limonene on those occasions when I need it. The MSDS doesn’t alarm me too much and I figure I consume a little of it every time I eat an orange. It’s all about exposure rates though; even water has a LD50.

My dad was a house painter when I was young. My brother and I cleaned his brushes in solvents that made our hands swell and turn red. When I was gainfully employed I did a lot of work in organic chemistry. 6 years ago I had to have a bone marrow transplant because of, according to the docs, early exposure to solvents. Since then I have focused on eliminating solvents from my shop. As a side note, I have taken to mixing my shellac in isopropanol. Rubbing alcohol. You can buy it from bulkapothecary.com. It is a solvent that is GRAS (generally regarded as safe)–they use it on baby butts! It dissolves shellac to the same extent as ethanol at the concentrations we are interested in, but since it evaporates more slowly It spreads nicely and I do not have to deal with brush marks if I go over an area. Don’t drink it though!

I’m going to read this again. And again. I’m (finally) retired after decades of small shop, production shop, fine furniture shop, and traditional boat building. Never have I done “commercial” finishing; there was always a “painter.” It was pretty much a standard quip that all old painters are crazy. Or missing some part of their respiratory apparatus. Or dead.

And actually, Chris, you (or whoever) would be doing hobby and small shop woodworkers a very large favor by completing this proposed book. No pressure.

Tung oil is my go-to finish because I am willing to put in the time, like the look and adore the durability. I have furniture I did with it 40 years ago that looks like it did when I finished.

The minwax brand tung oil does not seem to contain any tung oil from my reading of their MSDS sheet. I will try a brand advertising 100% pure tung oil.

The Real Milk Paint Company sells real tung oil.

“I don’t much use the word “feel.” I prefer the words “think” and “force poop.”

You sir would have made a funny, but frequently reprimanded Jedi.

So I guess it is a safe assumption that I won’t find any Potassium dichromate in your finish cabinet? That chemical was used with wild abandon in the Gamble house (1908) and originally was thought to be a treatment for sweaty feet. Nitrile gloves and gas masks are a requirement now though since it is one of the more deadly chemicals you can use in woodwork. It can produce an instant warm patina that will not fade, but then again it can cause a miserable lingering death, so I suppose it’s your choice.

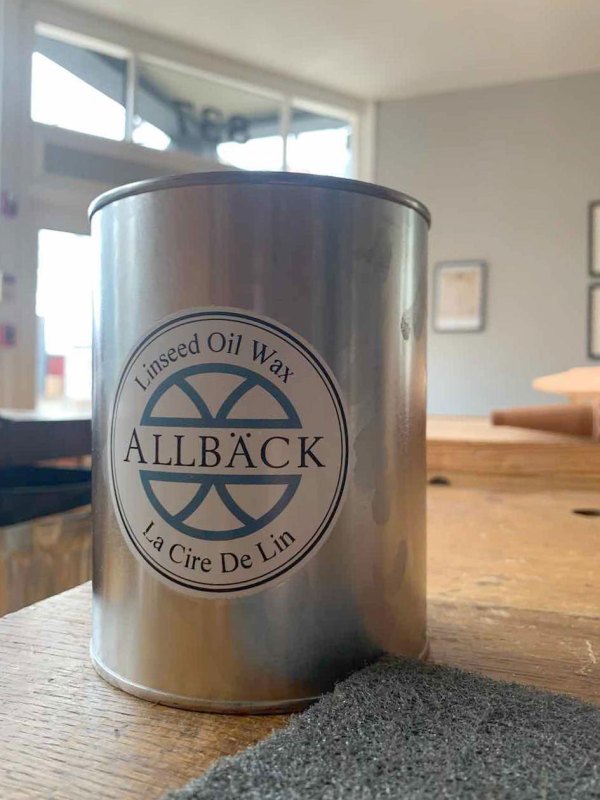

Just for information, apparently the Allbäck ‘Boiled’ linseed oil products (BLO and paint, not sure of oil-wax, but suspicious) revised their SDS recently to include ‘manganese siccative’, which I presume is some flavor of heavy-ish metal drier. Bummer for me; I was looking at their paint with a young kid in the house; now I’ll have more annoying precautions.

Somethings I’ve spent some time on without solid results: are chemical driers (excepting lead) mainly an inhalation exposure concern? Are they one of the things that are less concern after curing, or are they more like lead where it’s really an issue indefinitely via dust and chips?

Getting a little off topic and opinionated, but I did compare against common latex paints. What I saw mostly contained respirable silica, so I can’t say it’s convincingly better looking.

When it comes to siccatives. Allbäck, Ottosson and other manufacturers of high quality linseed oil and linseed oil paint add a lot less siccatives to their oil compared to your typical hardware store boiled linseed oil. Ottosson, Allbäck and the like use cold pressed linseed oil and purify it before boiling it and adding siccatives. You could also check out Selder & Company. They make oils and linseed oil paint without siccatives.

Do you still use Our shop finish recipe posted on January 23, 2020 ?

Yes. With odorless mineral spirits and stand oil. That makes it low in VOCs as possible.

During part of my time in the U.S. Navy I was stationed at Naval Station Annapolis where I was the craftmaster of one of the Yard Patrol Crafts (YP) used to train midshipmen in ship handling and seamanship. These are 109′ wooden hull boats with varnished cap rails on the gunnels fore and aft. Most of the other crews would spend hours sanding all the finish off and refinish with polyurethane. I hate plastic and instead of the sanding off 230′ of cap rail I had my crew buff it with 120 grit and apply a coat of spar varnish which is intended to be in the weather, unlike the polyurethane the other crews were using. While my cap rails always looked fantastic with minimal effort, the other boat’s cap rails would end up with hundreds of separation bubbles over the rails and they would be back to sanding. If the cap rails happened to get wet before the poly could be applied, it was even worse.

Lots of good information, thanks for sharing.

Great write-up! Sad to read that there won’t be a book. I definitely would’ve added that to my Anarchist’s collection. Woodworkers are relatively drama-free, but it seems like topics of finishes and sharpening are akin to politics and religion. Go figure.

Post bookmarked. May even put this together as a PDF as a quick reference guide. Thanks, Chris!

What do you think, if you have an opinion, about the Rubio / Osmo world?

I’ve used it. It seems like a lot of work. I haven’t read the SDS yet. Sorry.

I used hardwax oils (Rubio, Osmo, Fiddes) on a few pieces a few years ago. In my experience, it is no better than danish oil (or any oil/varnish blend) – either in terms of looks or durability, but it is certainly more $$. If you are worried about metallic driers, then look at T&T danish or or some of the Sutherland Welles finishes.

Real Milk Paint sells pure tung oil, pure hemp oil and nontoxic citrus solvent (not to be confused with the citrus cleansers).

https://www.realmilkpaint.com/category/oils/?gclid=Cj0KCQiAzZL-BRDnARIsAPCJs73sWmh494C1ZJNVd7P2VZKnPiNEepz84buRYly7nqZvqfgmSD9dnQwaAgv3EALw_wcB

Boiled linseed oil is bad stuff. Pure linseed oil is a different animal. Danish oil is linseed oil. Teak oil is linseed oil. Danish oil varnish is, well, varnish.

I was a professional house painter for 20 years. I did perhaps three jobs with safer paints and they were the most enjoyable. Restoring old wooden churches with chalk and egg tempera which we mixed ourselves. One hotel was painted with casein paint in the interior but we used sprayer.

Thanks for your article!

Circa 1850 is a brand of BLO without driers that is much easier on the wallet than t&t or art store stuff. I can vouch for a great finish. Dunno if it will ship from Canada tho. Amazon has a similar product by Plaza, and is be interested to hear any experiences with it.

Linseed oil paint and boiled linseed oil from specialised manufacturers like Allbäcks, Ottosson, Wibo are usually considered safe. The amount of siccatives is below the threshold for having to mark them as any kind of hazard according to the quite strict (stricter than the US) EU and Swedish legislation.

This article is one of my favorite all time. So well written with good content that I felt compelled to say “thank you.” so, Thank you!

Hi Chris,

Thanks a lot for this article. I was looking forward for this book and to be honest I still have hope that you´ll either change your mind about writing it or find someone who is willing to write it. Our daily life is already full of hazardous chemicals and I find the subject of non toxic finishes and materials a pressing one for the home and professional woodworker. Hopefully we will see changes in consumer behavior and manufacturer practices. Until then, I will try to stick to pure oil, non toxic waxes, milk paint and shellac (mixed with grain ethanol). There is a lot of potential market wise for non toxic products and the more I study the subject the more clear it is the urgency of changing our ways.

Anyways, as a long time lurker and first time poster I would like to thank you for all the work you do at Lost Art Press and for the woodworking community world wide.

Cheers

Once again, Dr. Schwarz, you have given away for free here some of your best work, obviously hard-won from your decades of professional experience. This is the best thing I have ever seen written for amateurs about the incredibly complex subject of “finishes and finishing”. As usual, you have approached this subject from a practical and sensible perspective, taking especially into account the health risks and consequences that can result from these products and activities. If there will ever again be a school subject taught (in any school besides Berea College) called woodworking, “industrial arts”, or even wood shop, this RIP book, never destined to see the commercial light-of-day, should be the first required reading, before ever picking up a tool. Of course everybody can then make their own choices about what risks they want to take afterward, but they would be doing so after being very well and responsibly advised about their risks and alternatives. Thank you once again, sir!

Thanks for this useful post! I’m new to finishing and learned a lot!

One question: what kind of soap specifically? Speaking of MSDS’s, there is no such thing as “plain old soap”. Most of the human body bars of soap have all kinds of additives and scents. Do you have a recommended brand?

I use Pure Soap Flakes and really like them:

https://puresoapflakes.com/

I’ve also found castille bar soap at my local snobby grocery store. No fragrance or detergent. I shredded it and it worked very well.

Hi Chris,

I’m a Ph.D. organic chemist by training and day job I work in the Pharma/Biotech industry. One weekends and some nights I woodwork. As a chemist, I have worked with all manner of nasty stuff. At one point, I had a job where they were basically going to put us in “space suits” for some work given how potentially dangerous the material was. I was glad when that company went bankrupt. In grad school, my Ph.D advisor wanted me to use a chemical I wasn’t familiar with so I looked up safety info on it. It was labeled as the most carcinogenic material known to man. I politely told him no and I’d rather get a 10% yield on my reaction than a 90% yield by using it.

You have given some good advice. As woodworkers, we have access to some powerful and dangerous materials that we really shouldn’t work with. You have given some good general advice on finishes. I don’t even like pressure treated wood. One day, I was at a local lumber store. A couple came in wanting to buy some wood for making raised beds for growing vegetables. The “salesperson” was steering them towards pressure treated wood. I had to step in. There is now way, no how you should grow veggies in pressure treated wood. I don’t even care if they say it is safe as I simply wouldn’t believe them. I steered them towards cedar. You might need need to replace it sooner but it is a much safer option.

Folks need to be careful at what they use and should read what you say. There is some stuff you can get rather easily that you should never use given the danger level. Your advice is a good solid start. As for me, I like shellac in 190 proof ethanol (I’m happy to pay the sin tax given the amt I use). I could probably be talked into using more Lindseed oil but I would get the stuff without drying agents added and just wait longer between coats for the oxygen in the air to cross link it.

Sincerely,

Joe

We used to keep soap flakes handy for washing our goretex and other delicates. Before I had a chance to try it as a finish it disappeared from all the usual retailers in the UK. When we enquired about it we were told that the only manufacturer had used a turn of the century machine for a critical part of the process and when it finally broke down it wasn’t an economic repair, terribly sorry but it’s only available in liquid form from now on. Disheartened, I turned my attention to milk paint instead.

Soap flakes are widely available in the U.K. Here’s one source:

https://play-learn.co.uk/product/soap-flakes/

Add glitter and food coloring for added fun!!

I think this is potentially the most important and influential piece Mr. Schwarz has written.

If you are trying to save this piece, use the Print button on the webpage, and then save it as a pdf. Do not try to do that with the email message containing the same text.

A few weeks ago, I received an email message from a dealer for a furniture company named Kalon Studios. I read quite a bit of their website, and found what they had to say about furniture finishes of interest.

From https://kalonstudios.com/care-maintenance/ :

Recommended Oil/Wax Finish

Kalon Studios recommends AFM Safecoat Naturals Oil Wax Finish. This is an organic plant-based premium hardener and sealer for woods. Alternatively Bioshield and Livos make a good wax finish.

From http://www.afmsafecoat.com/products/afm-naturals/afm-naturals-oil-wax-finish :

This organic plant-based premium hardener and sealer for unfinished woods works well on all ready-to-finish wood, bamboo and cork floors, and other interior wooden surfaces, including children’s furniture and toys. It contains a sophisticated combination of natural resins and waxes that together create a durable, water-repellant, watermark-resistant finish and sealer, enhancing and maintaining wood beauty and breathability. Based on natural vegetable oils, waxes and plant extractives, this product is free of lead, cobalt and citrus drying compounds.

American Formulating & Manufacturing

AFM

3251 Third Avenue

San Diego, CA 92103

Administration: (619) 239-0321

Technical Assistance:

Jay Watts (619) 239-0321 – X 102

Fax: (619) 239-0565

Contact Us »

Made in the USA

http://www.afmsafecoat.com/files/msds/4016-naturals-oil-wax-finish-msds.pdf

See: https://www.woodworkersjournal.com/afm-safecoat-paints-finishes-healthier-alternatives

AFM SAFECOAT PAINTS AND FINISHES: HEALTHIER ALTERNATIVES

BY CHRIS MARSHALL • AUG 29, 2017

Excerpt:

“Most paints and coatings will release unreacted chemical monomers (called outgassing) for two to five years AFTER achieving a full cure,” Pace says.

Sorry for such a basic question, but what are the 3 ingredients in the “Shop Finish” now?

I see above that you use Stand Oil in place of BLO. Are you still using the Helmsman Spar Varnish and odorless Mineral Spirits as posted back in January. Thanks in advance.

Yup. You are correct. Stand oil, odorless mineral spirits, spar varnish.

There’s a marketing person somewhere, probably at General Finishes, who’s working up a plan right now for relabeling their standard BLO as “Stand Oil”.

Has anyone tried the products from Vermont Natural?

A very much needed article. Thank you!

Thanks Chris. This was a great read. I’m hooked on your 2015 recipe for soft beeswax. But I probably missed a post somewhere along the way — are there more / less safe options for sourcing the turpentine? Thanks again!

TURPS is much less toxic. There are other citrus solvents available that I need to experiment with

I have used citrus solvent (from the real Milk Paint company). I thought it would be a good replacement for mineral spirits/turpentine/naptha. I thought wrong. The smell is more pleasant, but it seems to take longer to off gas, and it certainly does cause light-headedness if it off gases in a poorly ventilated area.

I will stick with Naptha. It flashes off and off-gases more quickly (it seems to be less oily). Better to get it over with than have the smell of orange flavored gasonline lingering for days.