For many American craftspeople (including many I interviewed who had a close relationship with James Krenov and his work), it appeared that Krenov emerged from Sweden a fully formed writer and cabinetmaker. That’s an understandable position; before the release of “A Cabinetmaker’s Notebook,” Krenov’s foothold in America consisted of a few short appointments at Rochester Institute of Technology’s School for American Craftsmen and Boston University’s Program in Artisanry, and a single article in Crafts Horizon in 1967, “Wood: ‘… the friendly mystery…’”. Many of his students in California, even from the earliest classes, assumed that Krenov’s career began with the success of his books, or that he had been relatively obscure before their publication.

Inversely, looking at Swedish magazines, furniture histories and newspapers, you might get the impression that Krenov’s story ends after his meteoric rise to fame and his departure from Sweden in 1981, just after the release of his books. While a few of his closest friends and colleagues in Sweden wrote about Krenov or included him in their writing on modern Scandinavian furniture, the line goes pretty silent there after Krenov’s resettlement in California.

A rewarding part of writing “James Krenov: Leave Fingerprints” was understanding and marrying these two disparate careers, and looking for the through-line to Krenov’s successes in both places. While this constitutes at least a few chapters’ worth of writing in the biography, I think it’s worth examining in a shorter piece as a means of understanding why James Krenov was a touchstone in the two different craft contexts in which he rose to renown.

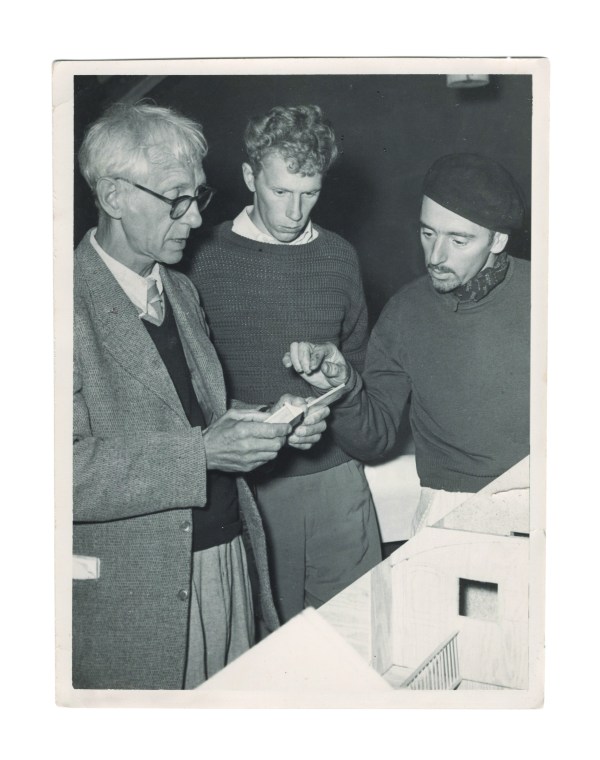

When Krenov came to cabinetmaking in his late 30s, he was an outsider in Sweden and its crafts scene. He attended Carl Malmsten’s Verkstadsskola from 1957 to 1959, and it was there he impressed his first, and maybe most influential, pair of advocates.

The first was Malmsten; by this point in his career, Malmsten was perhaps the best-known figure in Swedish craft, having risen to his stature by designing a huge volume of furniture that blended the honest construction of the English Arts & Crafts movement with a strong Swedish vernacular aesthetic. Malmsten designed for the simplest homes and the most luxurious Swedish state houses; he was a household name.

More behind the scenes, but no less influential among the tight circles of Stockholm’s art and craft scene, was Georg Bolin, the principal teacher at Malmsten’s school. Bolin was, by that time, an influential furniture maker and technician of the highest degree. He went on, through the latter half of his career, to design everything from fine furniture to novel “alto guitars,” and even a piano played for many years by Abba, Sweden’s second-largest monetary export, only outpaced by Volvo (until the arrival of IKEA).

As a student, Krenov impressed both Malmsten and Bolin. Shortly after his schooling, both men helped Krenov find a place for his work in the craft galleries and exhibitions of Stockholm, at a time when the Swedish craft scene was casting off functionalism for a more craft-oriented, holistic aesthetic that put craftspeople and handwork at the center.

While Krenov enjoyed minor successes in small shows and galleries (which any craftsperson would be proud to count on their resume), his inclusion in the 1964 exhibition “Form Fantasi,” at the Liljevalchs Kunsthall, was his big break. The exhibition was touted as a point of inflection in Swedish furniture and craft, and at the center of it were two of Krenov’s pieces, a wall cabinet and a silver chest. Krenov got into the juried show as a relatively unknown name (a newspaper article a few months prior misspelled his surname), but his friendship with Bolin and Malmsten certainly helped prime the judges for his work. (Both Bolin and Malmsten were also featured in the exhibition). When the Swedish newspaper Dagens Nyheter reported the event, Krenov’s “Silver Chest” was chosen for the feature photograph out of the 2,500 pieces from 250 craftspeople. After this show, Krenov won the favor of influential critics and curators, including Dag Widman, director of the exhibition and editor of the publication FORM from the Svenska Slöjdföreningen (Swedish Society of Industrial Design). This led to a solo exhibition, “Liv i Trä” (“Life in Wood”) in 1965, and a cavalcade of features, press and exhibition opportunities, as well as a stipend from the Swedish government given to artists and craftspeople deemed to be doing work important to Swedish culture.

While his cabinetmaking opened the door to his success, there is significant evidence that Krenov’s strong voice as a critic and singular personality helped him rise in the ranks of Swedish craftspeople. He started appearing at public conversations about craft at the Nationalmuseum (which appointed Dag Widman as its chief superintendent in 1966). At the time, Sweden was wrestling with the position of the designer-craftsperson; for a long time prior to the 1960s, Swedish craft had largely followed the trends of continental Europe, with a distinct separation between the designer and the person executing the work. With the revival in craft, Sweden saw an explosion of craftspeople who designed and made their own work, more akin to artists than potters, silversmiths, weavers and woodworkers.

Krenov did not see himself in either of these groups. His education had been technical, focusing on exacting execution according to measured drawings. Krenov eschewed this rigid process after his graduation, but did not swing all the way to the more free-form position of craft as art, which eschewed historic context and technical skill for expression and artists’ statements. His unique position between the two led to a lonely post as an advocate for designer-craftspeople working with traditional joinery and historic forms that were distinctly furniture. He focused on solid construction, graceful form and a distinctly functional intention, but made no attempt to divorce his influences and personality from a piece’s execution. Alongside his appearances at public discourses, Krenov also began writing for FORM, where he took on the voice of an advocate for craft against the bulwark of both unchecked artistry and functionalist design.

By the mid-1970s, Krenov was at the top of Swedish crafts; he was a featured presenter, author and craftsperson in many of the museums and galleries. Few could aspire to more, but his feelings of under-appreciation in Sweden (spurred on by his unique position between two trends) left him looking to the other side of the ocean for greener pastures. In 1966, Craig McArt, a student from RIT, studied with Krenov for several months and persuaded Krenov to share some of his writing. McArt brought an essay back to the United States – the one published in 1967 by Craft Horizons. This first contact with America, and specifically McArt’s advocacy, led to his appointments at RIT and BU. These were combative but engendered a small but enthusiastic following of U.S. students and colleagues. Krenov would have had no problem in Sweden publishing his first book, an extensive elaboration on Craft Horizons essay that became “A Cabinetmaker’s Notebook.” But he thought that in the States, unlike Europe, there existed a strong independence around craft, so there would be an eager generation of students who would be receptive to his philosophy – so he wanted his book published in English for an American audience.

And so, with the help of the RIT administration and McArt, Krenov published “A Cabinetmaker’s Notebook” with Van Nostrand Reinhold, a publisher of art and craft books based in New York. After its publication, Krenov’s reputation in the United States exploded (which surprised his publisher; it had hardly promoted its release). Three more books came in just five years, as did invitations to present and teach stateside, and a few particularly motivated craftspeople on the West Coast established a school based on Krenov’s idiosyncratic approach. It was the school that ultimately convinced Krenov to make his move across the Atlantic, but by 1981, it is clear (in his writings and correspondence from the time) that he had been looking for a landing pad in the States for the better part of a decade.

So, in truth, Krenov entered the American context at a particularly high moment in his career – it was among an American audience that he passed from renowned furniture maker to celebrated author, teacher and influential craftsman. In Sweden, his advocates called for the books to be translated into Swedish. They wanted Swedes to read the philosophy and sensitivity that both Swedish aesthetics and opposition thereto engendered in Krenov. The books were not translated, however, and while there are echoes of Krenov’s influence in Sweden’s woodworking trends (particularly in Malmsten’s schools at Capellgården and Krenov’s alma mater, the Verskstadsskola), his move to the States also largely closed the book on his lasting influence in Sweden.

Krenov’s aesthetic and technical approaches, however, were certainly born in his nearly four decades in Sweden. I would argue that his arrival and warm reception in America constitutes a potent reverberation of the European Arts & Crafts movement’s influence on American woodworking, with Krenov’s direct lineage from Malmsten, who had visited Gimson and the Barnsleys in the Cotswolds in the 1920s. Krenov rose from the plateau of fame he had reached in Sweden to an even higher perch in America, on the back of both his writing and the establishment of his school. If nothing else, he was a singular presence in both countries; his resonance with the curators and critics of Sweden was matched by his reception among the dedicated woodworkers of America – those who were looking for a different approach than the technical manuals that dominated American woodworking publications in the middle of the 20th century. Neither country can claim Krenov as their own; certainly it was Sweden that fostered his development, but it was the United States that gave him his biggest audience, an appreciative student body and a warm reception.

But Krenov never found exactly what he was looking for. He was a Russian-born, American expatriate living in Sweden for decades, including the first two decades of his career as a woodworker. For several years in the 1960s, before the Schneider v. Rusk decision on the status of naturalized U.S. citizens living abroad, he was even a stateless person, having lost his naturalized American citizenship after not returning to the States for several years. While he regained his citizenship in the mid-1960s, it is perhaps most fitting to consider Krenov a stateless craftsperson; it suits his position as an independent force in both countries, someone who never settled for the successes he won.

A story that might sum up his tireless, even contrarian, position was told to me by Tina, Krenov’s youngest daughter. She recalled that in Sweden, when she was growing up, her father insisted that they find turkey for their Christmas dinner, something he remembered from his teenage years in Seattle. But upon the family’s resettlement in California, where turkey might have been much easier to procure, Krenov insisted on ham for their holiday dinner, as the Swedes had preferred. It might be this resistance to comfort that gave Krenov the drive to look to the next opportunity. It is certainly a factor of his success in Sweden, and the driving force behind his relocation to California. With this lens, we can see the continuity in Krenov’s seemingly separate careers in Sweden and the United States, and we might better understand how the perceived loneliness or isolation of his approach ended up bringing him a wider audience and community than any one group or country could have provided.

Insightful and nicely done!

This is a well written overview, but I was disturbed by some spelling mistakes:

It is called Liljevalchs Konsthall, not Kunsthall.

Malmsten’s schools are called Capellagården and Verkstadsskola.

Keep up with your good work!

Thanks Bengt! The pains of writing across a few languages… I promise the book had Swedish eyes on it that this post didn’t!

Perhaps his move was also in part driven by the nostalgia of the west coast, where it seems from his writings, that his childhood years spent between Alaska and Seattle, had a profound impact on him.

Comment? The man, himself, filled me with wonder and a desire to follow…

I really appreciate all of this, Brenden. Having dedicated this chunk of my life to the school, and continuing to live in Fort Bragg, it’s interesting being a part of the ‘culture’ around him and the school without ever knowing him. A bit like my grandfather, who was a large figure I never met but who’s shadow I could usually feel, or even working at Apple – I started the week of Job’s funeral, which was an interesting time to see people grapple with that legacy and how they moved forward. The hardest part of any figure like this, be them family, artists, or builders of the institution of one’s employ, is knowing the whole person. Not just the engraved plaques with their names on them, or photos with their trophies or masterpieces or triumphs, but who they were that created the fellowship of people around them and what they did. My grandfather was a people leader, who led 100 boys to be Eagle Scouts. Jobs had a vision that attracted more loyal employees than I’ve ever seen. I like how you approach all the facets of his life – from my time at the school, the man of the classroom and the man behind the words of the book sound like two different people sometimes. The truth is, he was three or four or five, it seems. Stateless, rebellious. Some of his followers will only do things how Jim would have. Some fought with him. But even in his work, and his writing, where he’s done something I don’t love or wouldn’t be interested in doing myself, I always find beauty.

Very, very nice.

“ABBA Sweden’s second-largest monetary export, only outpaced by Volvo (until the arrival of IKEA).” I’m probably the only one to care but… but I’m pretty sure Ericsson has them beat. Actually, I don’t care, but I do hate both ABBA and IKEA. Notwithstanding–Excellent! Can’t wait to read it.

I think you’re right about Ericsson – what I meant was that, at the time, ABBA outpaced everything until IKEA came around, but after IKEA dethroned ABBA, it looks like Ericsson then displaced IKEA. H&M and Volvo are up there, too. But the fact that ABBA was such a huge export is still fascinating to me – and I can’t say I don’t love them (for some reason, I grew up listening to ABBA at home).

You had to have been there in the 70’s… woodworking was ShopSmith ads and knotty pine hutches. Then the Krenov book came out. A guru was born!

In 1979, I was a 3 year Cabinetmaker. I purchased ” Cabinetmakers Notebook” and was inspired.

In June and July of 1980, I attended a 6 week workshop at the Mendocino High school woodshop, with Krenov as our mentor. If you, as a craftsperson, do your work with your Head, Hands and HEART, then you are on the right path to making something precious.

In my living room, currently, I am sitting with the handplanes and cabinetry that I built at this class, 40 years ago.

4 years after this class, as an 8 year journeyman cabinetmaker, I wanted to find a cabinetshop that insisted on Monumental Architectural quality as deemed important to me because of Krenov’s quality and his work ethic.

Our cabinetshop did all of the Architectural Millwork and cabinetry for the Ritz-Carlton, all over the world.

Also, our cabinet shop built a 1″ to 1ft scale model house of Bill Gates house in Medina Washington. Imagine a 75,000 sq inch model dollhouse of a 75,000 sq ft real house that Bill and Melinda wanted to live in. Who gave me the determination to work 103 hour weeks to complete this project in a high quality fashion? Krenov did.

When the dollhouse was complete it was shipped to New York City to be viewed and remodeled by Bill Gates and his Architect: Thierry Despondt. I went to New York City and spent 3 non stop weeks of 14 hour days to demonstrate my Krenovian derived work and quality ethic.

Then, after the dollhouse model was complete, it was set-up at Bill Gates home construction job-site for All of the trades to follow. ( No 3d computer drawings were used on this project in 1994 )

Krenov to me is 4H: Head, Hands, Heart and Home: sounds simple, but anyone from or in the rural country knows simple is Not easy at all.

I would genuinely cherish anyone willing to communicate with me about Krenov, because I know it would help me (at 67 years old) return to a more beautiful way of crafting.

Thanks and take care

Mike Luther

OK to text me: 5752079682