This is an excerpt from “The Essential Woodworker” by Robert Wearing.

In making plain or flush doors the obvious choice of material appears to be a well-chosen board of solid wood (Fig 353). However this is no solution since the wood may swell or shrink, spoiling the fit, or warp, making any fit impossible. A stable, light door suitable for painting or lower-quality work can be made from a mitred frame to which are glued two sheets of thin ply (Fig 354).

A heavier and more robust door is shown in Fig 355. Here a stronger frame is dowelled or tenoned together with two ply skins. Extra cross members are added to stiffen the door. Air holes are drilled in the cross members and in the bottom rail to equalize air pressure inside and outside. Such cross members must not be too far apart, nor should the ply be too thin (minimum 6mm (1/4in.)), otherwise an impression of the framing may show through.

A door from multi-ply or blockboard is extremely stable, but the edges are unattractive and do not take the hinge screws well. Such a door is generally lipped (Fig 356). The lipping may be butted or mitred at the corners. The tongue is essential for good adhesion, particularly on the end grain of blockboard. The lipping may be applied to veneered material but for better work the lipping is concealed by veneering the whole face after the lippings have been glued and planed flush. Lippings must be made from thoroughly dry material, otherwise shrinkage will take place and the lipping will show through the veneer.

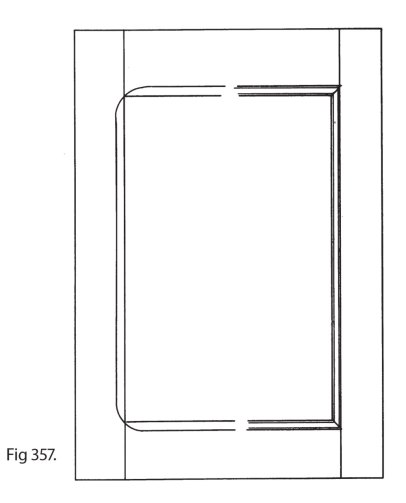

Good-quality handwork makes frequent use of the framed and panelled door (Fig 357), the inner edge of which is moulded or chamfered. The following illustrations show some of the possible combinations of frame and panel.

— Meghan B.