One of the ideas that’s been crashing around in my head for years is that vernacular furniture – what I call the “furniture of necessity” – is divorced, separate and independent from the high styles of furniture that crowd the books in my office.

This idea is not commonly held.

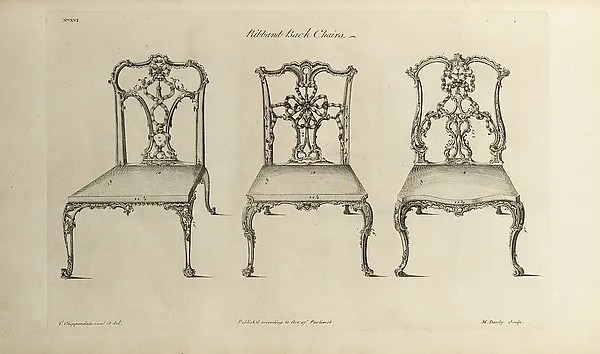

The conventional wisdom is this: Chippenton Sheradale invents a style of furniture that is Neo-Classical Chinese. So he publishes a pattern book to illustrate his new pieces, and the style becomes all the rage. All of the rich people want pieces in Neo-Classical Chinese to replace all the pieces in their houses that were Neo-Chinese Classical.

So the local cabinetmakers oblige and (as a result) can all afford new chrome rims for their carriages.

Rich rural farmers see the pieces in the new style and return home with the crazy idea that they should also have pieces in the latest Neo-Classical Chinese style. So they get Festus, the local cabinetmaker, to build them a Neo-Classical Chinese chair. But Festus uses Redneck Maple (Holdimus beericus) because Festus can’t get New Money Mahogany (Stickusis inbutticus).

Oh, and Festus takes some liberties with the new furniture style to please his rural customers, who want a series of cupholders in the arms that can accommodate a Bigus Gulpus.

Then the poor farmers see the Redneck Maple Neo-Classical Chairs owned by the rich farmers and ask their local carpenters to make copies, who also make changes to the design (a gun rack on the back). And then the dirt farmers see that chair. And so on.

Meanwhile, back in the city, a furniture designer draws up a pattern book for Neo-Gothic Romanian furniture. The cycle begins again.

All this sounds plausible because it has been written down in almost every book of furniture history ever published. The rich make something fashionable, and the poor imitate it until the rich become annoyed or bored. So then the rich find a new style, which the poor imitate again.

The only problem with this theory of degenerate furniture forms is that the furniture record doesn’t always go along with the theory.

I think there’s furniture that is divorced from the gentry. Furniture that is divorced from architecture. Instead of beginning with a pattern book, it begins with these questions: What do I need? What materials do I have? What can I make that will take little time to build but will endure (so I don’t have to frickin’ build it again)?

For several months now I have been plowing through “Welsh Furniture 1250-1950” (Saer Books) by Richard Bebb and have been thrilled to find someone who thinks the same way. Bebb has done the research on the matter when it comes to Welsh furniture. And he has convinced me that I’m not nuts.

In the first section of Vol. I, Bebb deftly eviscerates these ideas like a fishmonger filleting a brook trout. It’s an amazing thing to read. I’ll be writing more about Bebb’s research in future entries, but if you want to get right to the source, I recommend you snag your own copy of this impressive work.

— Christopher Schwarz

I’m a believer. >

A furniture version of Dr Seuss’s “The Sneetches”. Human nature.

Few things in life offer greater delight than than when someone confirms “You were right!”

Reasonable theory. Explains why some things

like, for instance, something local to me, a

Taunton Chest, is repeated all up and down the east

coast, but called all different names but still keeping

roughly the same form factor.

Love the Latin names! Igpay atinlay?

/Ted

How about the Shakers?

Tico,

I’m not exactly sure what you are asking.

Were the Shakers outside of the influence of furniture styles? Absolutely not (in my opinion). Shaker furniture is, to my eye, a good selection of English vernacular forms that were taken to an extremely high level of craftsmanship. And they were definitely influenced by the outside world (later pieces show significant Victorian influence).

But by no means were they degenerate in their imitation. Instead they took basic forms and elevated them.

And that is why we remember this relatively small group of remarkable builders.

Theirs was a “furniture of necessity”, that’s what I meant to comment on.They needed it and innovated many ways to make it, and, at the time of making (Victorian) went against the cultural stream. Charles Dickens despised their plain, austere style, as did many other contemporary observers.

Personally, I prefer Classical Neo-Chinese.

I’ll take a pint, with shrimp eggroll.

Although impressed with the craftsmanship of the old furniture makers who produced the Chippendale, Sheraton and Queen Anne styles, and similar, I have never really liked the finished articles. I find them fussy and impractical, and not necessarily durable in real life (although in genteel households with servants they lasted well). Country chairs I love, together with the country furniture to go with them.

Regionalism can play a role too. A geographical area can gain notoriety for a distictive style and will not be bothered with outside influences; the object becomes a kinship of tradition and place. Kind of like Cincinnati and its chilli.

I build things from my minds eye. I don’t sketch or draw, I just go into the shop and make it when a piece is needed. The build always goes well. I sell nothing, I make it for myself or give it to my children. If it were to be described as a style, it would be Arts and craft. I like plain and so do my children.

Years ago, I lived across the street from a wealthy socialite who was a widow and needed someone to do “chores”. Shovel snow, repair things, clean things etc. Her home was furnished with some of the “plainest” furniture I’ve ever seen, plain Victorian I called it. Cheap and dark I thought, until I was tasked with removing her fine china from her china closet to clean. The entire case was made of African Ebony and Rosewood. The chairs and couch upholstery was fine weave cashmere with woodwork of African mahogany. Although at first glance everything looked “peasant” it was all constructed well with the finest materials and all of it commissioned. Built to last generations, plain to suit everyone of later generation and of proper inventory she claimed.

After several years, she went on a trip to New York for a class reunion at Cornell I think. She brought back a chair for me to sit in when I was doing things like polishing her silver ware. After sitting in it for a couple of hours, she asked me if the chair was comfortable and I replied, “yes and the quarter sawn oak is beautiful.” “Where did you acquire it?” I asked. She replied, “from an old friend, it is a Stickley.” I shot out of that chair aghast that I was sitting in what should have been a museum piece. She asked with a smirk “Did you sit on a tack?” “That’s an antique” I said. I should not be sitting on that chair. Walking away she stated “that may be, but it’s mass produced pieces for servants quarters, common folk and toilers.”

I think furniture styles and pedigrees are subjective. I made a chair for my daughter that turned out beautifully, matches nothing in her home, and that she truly loves and would not trade for 20 Stickleys. I am a nobody, but what makes it so valuable to her? Why did the socialite think the Stickley chair was so much fire wood? Maybe, like beauty, the pedigree and style of furniture is in the eye of the beholder. Clearly the Socialite had the financial wherewithal to purchase or commission Chinese whatever but she did not. Instead, she went for plain and well built that was commissioned on her “coming out”. My only requirements for furniture is that it be plain styled walnut, mahogany or oak and be needed. Oh, and be built by me.

“And he has convinced me that I’m not nuts.”

[The snark snipes here.]

Sounds like when Homer designed a car

Sometimes the wealthy emulate the poor and buy new jeans with holes in them.

And then the poor save up all their money to buy holey jeans…. Weird world. Someone ought to sell tickets.

Earth has been the biggest tourist draw in this quadrant of the galaxy for several centuries. Occasionally some redneck alien crosses the rope and we see it. Of course the shadow government knows, but they take their cut of galactic blarsts and silence the witnesses. I have a website with all the details, only $9.95 (earthican) per month.

*rimshot*

Furniture history is a very broad subject. The humorous article you wrote above is funny, and just “inside baseball” enough, so that the cool kids (woodworkers) can get the joke. It’s also a bit strawman-like, is it not? I think there’s ample support for the notion that pieces of high-style, sometimes the very highest, did inspire copy-cat work among people with lesser means. Frankly, to suggest otherwise is ludicrous. Farmhouses could be counted on to have benches with simple, rudimentary construction, but many country-made pieces exist with pretense to be something they’re not, or honest imitation of high style within the means of the patrons. You’ve seen wood panels painted to imitate crotch mahogany, yes? Sometimes these can be pretty bucolic, but it’s easy to see what they wish they had.

The short answer is that provincial and rural craftsmen – and their customers – have always drawn inspiration from a variety of sources and these have, of course, sometimes included the fashions of the elite.

But the notion that the fleeting tastes of the elite are the sole or even principal influence is incapable of accounting for the variety, quality and sheer durability of the furniture that survives from the “lower orders”. Vernacular traditions frequently display a capacity for development and innovation and, indeed, have often been taken up by the elite themselves.

The problem is that the theory of hierarchical diffusion, that is, that ideas invariably and predictably move down the social scale because everyone wants to imitate their superiors, has been the only game in town in the academic study of furniture. It is an idea that is rooted in an obsession with the houses and lifestyle of the wealthy and, having been side-lined in modern theories of cultural change, only lives on in certain corners of the study of the decorative arts, including mainstream furniture history.