When war broke out in 1939 there was great concern over the losses that might occur in Britain due to bombing, possible invasion and war operations. At the same time Britain was seeing the same changes America was experiencing: the loss of rural industries, the growth of cities, roadways overtaking small towns and mass production practices displacing small businesses and farms. Taking inspiration from America’s Federal Arts Project Sir Kenneth Clark the diector of the National Gallery initiated a program titled, Recording the Changing Face of Britain. He also estsablished a similar program, The War Artists’ Scheme.

Lists were made of sites that were to be documented with pen and ink and watercolor. The goal was to record those sites considered typically English (little of Wales was included, Northern Ireland was left out and Scotland had a separate recording program). There were 97 artists involved with over 1500 works completed. The Pilgrim Trust (funded by American millionaire Edward Harkness) was used to commission works by prominent artists and to pay small sums to other artists who submitted their work. In 1949 the Pilgrim Trust gave the Recording Britain artwork to the Victoria and Albert Museum and the illustrations shown here are from the V & A collection.

One of the ‘other’ artists was Thomas Hennell and he is featured here because he specialized in drawing and painting the countryside and the craftsmen of the countryside. Hennell suffered a mental breakdown several years before the war started and was not eligible to serve with the armed services, however, when war broke out in 1939 he offered his services as an artist to the War Ministry. He drew and painted for the Recording Britain project and was also dispatched to record war preparations. By 1943 he was a full-time and salaried war artist. He participated in D-Day and traveled with the Canadian First Army and later, a Royal Navy Unit, as they advanced during the invasion. In June 1945 he landed in Burma and there documented the end of war operations. Hennell was 42 years old when he was killed in Indonesia in November 1945.

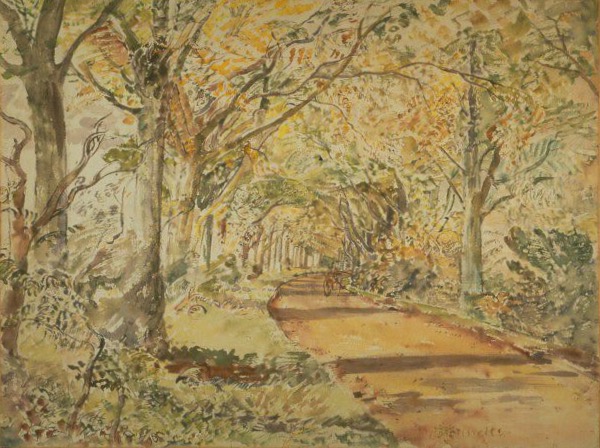

As the war progressed the original lists had to updated as areas of Britain not considered priorities were threatened by bombing or the need for military bases. Hennell was quickly dispatched to Lasham when local residents figured out where an aerodrome was to be built and the Beech Avenue, a stand of trees first planted in 1809, was to be destroyed. From Volume 4 of “Recording Britain” by Arnold Palmer, “…by the afternoon post a letter was dispatched to the artist. Before his [Hennell’s] answer came, he and his hard-working bicycle were well on their way to Hampshire.” To give you and idea of the size of the Beech Avenue and its importance four-fifths of the trees were felled for the construction of the aerodrome leaving two short lengths totaling a quarter of a mile.

In the early years of the war Hennell captured several craftsmen in their shops carrying on with their work. Although they were living in a time of great uncertainty, and each day’s war news brought more anxiety, there was always the shop to tend to. A new order came in, repairs were needed here or there and each job in the shop gave some small sense of normalcy.

Hennell seems also to have captured the ‘personality’ of the various shops. Mr. J.W. Brunt’s wheelwright’s shop seems well-ordered compared to the controlled chaos of his smithy (in the gallery below).

The artists that helped create the works in the Index of American Design and the Recording Britain program helped document handmade objects, scenes of daily life and landscapes many of which now exist only on paper. Thankfully, during 1940 and 1941 before he became a full-time war artist, Thomas Hennell completed 33 drawings and watercolors of the English countryside that included several craftsmen’s shops.

Which makes me wonder how many of you have documented your shops, or your corner of the dining room, or basement, or garage? Have you made a sketch of your shop or asked your talented daughter/son/niece/nephew/grandchild to make a sketch for you? Whether a masterpiece done in crayon by a five-year-old or sketched by your art student teenager, either would be a treasure.

-Suzanne Ellison

In the Newington Smithy sketch I’m pretty sure the jumble of gears and wheels on the right foreground is a ‘patent’ tyre upsetting machine which automatically upset and scarfed the ends of wagon tyres for welding. Depending on the model they also sheared the iron to length, rolled it to near finished curvature, punched bolt holes and several other essential wheelwright’s smithing functions. Sort of the ‘Shopsmith’ of ironwork.

Most now sadly melted down as scrap or embalmed in ‘folk museums’ missing several parts and slowly rusting away.

Thanks.,I wasn’t sure what the gears & wheels might might be.

Bernard Naish

2015-11-25 08:25:56

Suzanne, Wonderful drawings and interesting piece about English history. All the places named are well know to me. We, that is I and other members of our Club, keep this web site up to date with our details and our work:

http://www.bowoodcarvers.co.uk/index.html

I do not know how to make this web site permanent, as it were. I mean preserve for prosterity?

I mean are there any national archives for such things in the USA or England?

http://www.webarchive.org.uk/ukwa/

Bernard, you can also try the Google Cultural Institute for images from museums and databases around the world: https://www.google.com/culturalinstitute/home?hl=en

By the way, have you started work on the misericord?

Wow Suzanne, as usual, these are really beautiful scans! I’d love to read more about your research methods and the query techniques you’ve learned for finding such illustrative woodworking documents amongst the world of digital archives.

Another excellent article Suzanne.

Thank you for it.

My shop is photographed, but not sketched.

Some of these sketches are masterpieces.

Keep up the good work.

Really enjoy your writing.

Eric

central Florida

Thanks, Eric. Now get your sketch book out and get to work!

Suzanne,

I really appreciate your research and how you relate each story to the reader. This story is fascinating to me, and I love the sketches. Thank you.

Thanks, Dave! Thomas Hennell’s countryside work is wonderful and his story easy to tell.

Thank you for this blog – I knew of Thomas Hennell, but not seen these images before… I guess the Wiltshire Wagon was being built in the Aaron White’s shop at nearby Corsley…. I went to school with his grandson – sadly never visited the wagon works… Now long gone and houses built on the site…

Bob, the best part of writing a blog post is when a reader lets me know he has a connection to a place in a sketch or painting. Thank you!