The writer of a popular tree book once stated that the white pine of our northeaster States was destined to disappear except for ornamental purposes. There are many reasons to believe that that time will never come, yet the nature and habits of the tree and the shortsightedness of the people make the statement more than a mere suspicion.

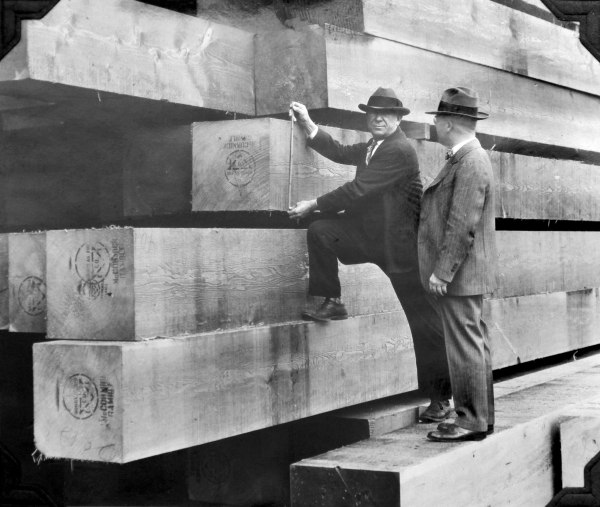

Not a great many years ago within the white pine region, there were magnificent stands of old growth pine. Every old inhabitant today will tell you how they stood on his father’s farm when he was a boy, their clear, straight trunks and gnarled flat tops high above everything else. Many an old house back in the country has floor boards and cupboard doors that are more than three feet wide which were made from such trees.

These old monarchs of the northern forests are gone now, except for the isolated trees or clumps scattered widely over the region. A woodlot owner recently guided me several miles back into the hills in order to point out three magnificent pines which have been standing probably for more than 250 years. One could never mistake them from others of a later generation.

Before the advent of the portable sawmill it was unprofitable to cut and haul logs any great distance to market. The trees were felled, rolled together, and burned when new lands were cleared. “Log rolling” days are still pleasant memories to New England’s oldest inhabitants.

Those were the days of the large farms with great herds of cattle and many oxen. Sheep roamed the hills in far greater numbers than they ever do today. Immense areas were required for pasturage, and extensive fields supplied the hay and grain for the winter feed. Ox pastures are not known today, yet they were common in the days gone by.

Today, farming has moved westward, and large farms in the hills have been reduced or abandoned entirely. It is true, of course, that men have learned to cultivate small areas often as profitably as their fathers did larger tracts of land. Every industrious farmer went over his pastures each year and removed every chance pine that had seeded from some adjacent tree. Now every wise farmer leaves the young pines to grow.

It may not be very strange to know then that today there are more acres actually growing trees than there were 50 or 60 years ago. There is not more timber, of course, for much of the valuable forests have been removed within the last fifty years. Such land is now covered with a poor quality of hardwoods. The valuable forests today are the old fields and pastures which have grown up to pine.

Everybody knows that broadleaf trees, such as birch, maple and oak, usually take the place of pine when it is cut. The pines do not sprout as a rule, and when a pine forest has been cut over without leaving any trees for seed there is no chance for young pines to again occupy the land. Worthless birch and maple, with their light seeds, usually take possession of the cut-over lands.

This type becomes known as sprout growth and is of little value to mankind. White pine, deprived of its right to the cut-over lands is, however, the predominating tree of the abandoned fields. The owners no longer cut down the young pines, but encourage their growth. In a suitable soil, with sufficient light and with occasional mature trees to provide the seeds, the abandoned fields alone are providing for our future commercial timber.

A southern New Hampshire lumberman recently stated that if he had left a few sturdy pines for seed trees on the woodlots he has lumbered during the last thirty years the present value of the young growth would be worth more than all the timber he has cut during his lifetime. There are thousands of acres of land, once growing pine, which are now producing nothing better than gray birch and maple.

Often fires have been allowed to burn over the ground until the only growth remaining is scrubby and worthless. But fires are not the menace they used to be. Farmers are learning the value of young pine growth and the starting of fires to clear land is not common. Fires set along railroads and by careless boys are now the most serious ones.

With increased safety to forest growth, planting becomes more and more a desirable investment. Every acre of land should be producing something of value to its owners is the general opinion of every land owner in this era of progress. The planting of white pine is often the only means of getting an income from some lands. All the vacant land and pastures cannot seed themselves, and the cost of planting them will soon be paid for by the increased value of the land.

But many people say: “It will never do me any good. I will never live long enough to realize anything from my labor and expense.” Experience of hundreds has shown that this is a grave mistake. One does not have to wait until their planted lands have grown merchantable timber. Everywhere people are seeking to invest their money in young timber, and they are willing to pay good prices for it.

Many farmers are planting all their vacant and worthless land with pine and chestnut and are buying similar land of other people for the same purpose. Where the expense of the operation is ten or twelve dollars per acre, in a few years the land will be worth forty or fifty dollars. Such investments easily bring 5 to 7 per cent interest to the owner on his money invested.

It is little realized that growing trees on the rough New England hillsides can with a little care be made to accumulate a cord of wood per acre annually. Such is the case, however, and it is needless to say that one does not have to invest his earnings in copper or other doubtful stock from which he may never see any returns.

There are many ways by which an owner may seed up his waste land with pine. Some people have met with fair success by gathering the cones early in the fall before they open, drying them out, and scattering the seeds during the winter or early spring. It is better still to drop the seeds, a few together, in spots previously cleared of grass or turf and then press them into the soil with the foot.

Successful planting of wild seedings is often down by transplanting little trees growing in thick bunches or in the shade where they can never mature. The most successful planting is done with trees—two or three years old—bought from nursery men and set out five or six feet apart each way. This should be done in the early spring before the growth starts. Chestnuts should be kept in moist sand over winter and planted in the spring. They grow rapidly.

The advance in prices of lumber and the extensive box and cooperage mills throughout the northwest have made sad inroads in our timberlands. Not only is the old growth timber largely gone, but lumbermen even find a profit in trees that are scarcely six inches in diameter. The time is past when trees can be allowed to grow to immense size. It is figured that pine yields the greatest returns for the money invested between the ages of 40 and 60 years. Chestnut requires even less time.

Those who have studied the matter say that the time is at hand when the forests are to be considered as crops to be planted, thinned and harvested like other crops. When this practice becomes more universal and people learn more clearly the value of growing timber, there will not be thousands of acres of unproductive land in every State, a constant eyesore to the people, and yielding no returns to the owners.

The United States Forest Service at Washington furnishes free of charge pamphlets and other information on the methods of planting desirable species, and where the seeds and young plants may be obtained, together with a range of prices.

The Herald and News – June 23, 1908

—Jeff Burks

My grandfather is an arborist and started our family’s tree service here in Massachusetts. He taught me when I was a young boy scout how to plant young white pine saplings. The one I planted is still growing strong in my back yard. This article makes me think I should go out and plant more of them…

Interesting re-post. I live in southern NH (Merrimack) and have 3 acres of land that can definitely fit that description. As far I as can tell this whole area was clear cut and farmed through the late 19th century when commercial farming in the mid-west decimated the area and the economy focused on other industries including the many textile mills on the Merrimack River in Manchester and Nashua. (A great look at that and the connected New England farmhouse that resulted from Yankee farmers trying to adapt is the book “Big House, Little House, Back House, Barn” by Thomas Hubka.) The back acres are all red oak, white oak, birch and eastern white pine. There seems to be a pretty healthy mix of all those species and from clearing some the trees seem to be 125-150 years old and most over 100ft tall. Over that time and ownership changes I think the forests in this neighborhood were left to their own devices. The Eastern White Pines seems to have grown straight and tall in fairly dense stands — the wood from them has been great to work with. The hardwoods, while some are sizable with 2′ and larger diameters are often twisted and bent yielding poor quality wood as they either grew from cut stumps and/or fought for light in the shadow of the faster growing pines.

“Every acre of land should be producing something of value to its owners is the general opinion of every land owner in this era of progress.”

The old forests provided vast habitat as well as timber. The opinion of that age, and extending much too far into this one, is the primary reason why the old growth is gone, and why wildlife has also been largely decimated. Not everything on Earth needs to ‘produce’.

Every time I wonder the woods around my home, I think about this. It’s a very rare to encounter any trees older than about 100-150 years.

It’s fun to imagine the author waxing nostalgic about the “way things were”. And if he only knew what would become of chestnut trees…