“In the past, the carpenter’s guild enjoyed great prestige. To be a house carpenter was to know how to lay out and join, with precision, the often huge systems of trusses needed to support the enormous weight of a roof in stone or tile. At the time it was very learned work, and lent to those who practiced the art an uncontested predominance.”

— René Fontaine, architect

On the 31st of January, 1783, André-Jacob Roubo stood on a platform 38 meters (125 ft.) above the streets of Paris, which spread out around him in all directions. He was just below the pinnacle of the wooden dome he had designed to cover the round interior courtyard of the Grain Market near the center of the city. The structure spanned 39.5 meters without any internal support, and it had been constructed of an uncountable number of spruce planks, laid out and precisely joined by a small army of carpenters.

Far below, the carpenters were removing the last of the scaffolding that had supported the structure during construction, and, from a safe distance, a large crowd had gathered around the small band of officials from the market and the city.

There had been no volunteers to join Roubo at the top. Would it all come crashing down?

France loves its bread as much as it loves its wine.

When the merchants in the market grumbled about the lack of space and the shambles in the courtyard, Paris listened and decided to put a roof on it. It would have been possible to build pillars to support the weight of the structure, but in the spirit of the enlightenment and of Paris, they decided to stretch the limits of the possible, and they engaged a couple of architects to build a dome.

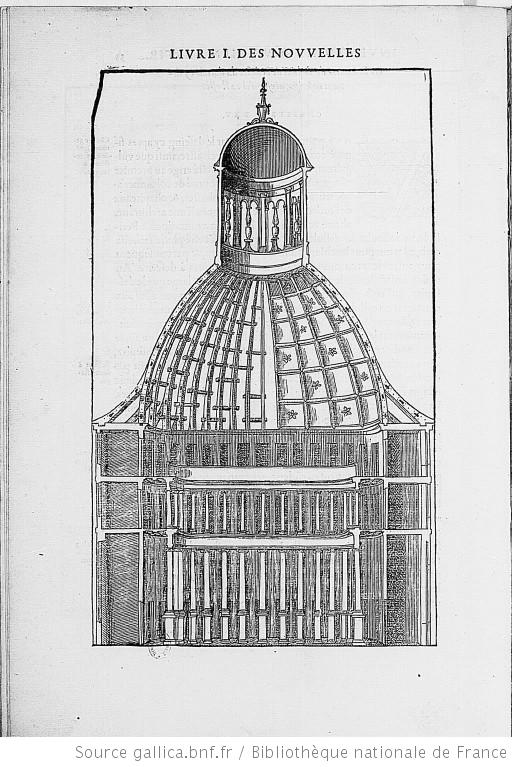

It was a complicated project. There existed in the world at the time domes of a similar size, the Hagia Sofia in Istanbul was 31 meters, the Pantheon in Rome, 43, and the Duomo in Florence spanned 44 meters. But as the noted French architect Louis-Auguste Boileau wrote in a short biography of Roubo in 1834, the market had been built over a number of much older foundations of uncertain strength; and the structure, with its relatively thin walls and all the arches, had not been designed to, and could not possibly be expected to support the weight of a dome in stone and/or brick. Plus, it was a market after all, and the money and time needed for such a structure would have been a deal-ender.

The dome would have to be built in wood. But who could design and build a wooden dome with a span of 39 meters? One of the architect’s assistants had the answer: There was only one man in France who might be able to get the job done.

In early 1782, Roubo received a visit from the young architects, Legrand and Molinos, who had been engaged for the project. He listened to what they wanted and said he needed a night to think about it. The next day, he told them he would do it, but only on condition that he would be free to build the dome as he saw fit.

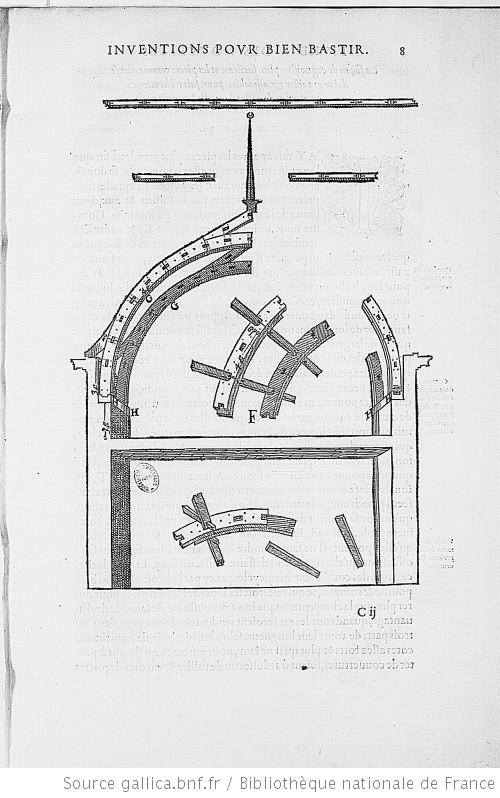

The details of the conversation were not recorded. But as Boileau wrote, Roubo, who had just finished his masterwork, the series of books “L’art De La Menuiserie,” had an ace in the hole, another book two centuries old. One can imagine him listening to the architects outlining the project and its constraints, and then after asking a night to think about it, pulling a dusty big book off the shelf in his study or in a library. “Inventions to Build Well at Low Cost” (“Inventions Pour Bien Batir à Petites Frais”) by the architect Philibert Delorme, who had worked much of his career for the French king, Henri II, but had been mostly forgotten by Roubo’s time.

The book included way of building various kinds of arches, using ordinary planks intricately joined with pegs, notches and wedges. The arches are joined together using an integral network of wedged crossbars to form a vault or a dome. The result is a remarkably light and modern construction that concentrated the stresses in tension and compression to take advantage of the strengths of wood and prefigured similar designs in iron and steel. It was in sharp contrast to traditional wooden roof structures based on the triangle, where the maximum span was dictated mostly by the wood available in suitable length and dimensions for the base.

The construction took only five months. But, as you can imagine, when building a new type of structure at that scale requiring countless thousands of pieces of wood that are shaped by hand to very high tolerances by a small army of carpenters, all did not go to plan. Boileau in his biography wrote: “(H)e encountered difficulties of every type, and personally checked and adjusted if need be, the numberless pieces of wood… ”

So on that January day, the last of the scaffolding was taken away. The crowd held its breath. And nothing happened. Roubo’s design had worked. The waiting crowd swarmed into the Grain Market and carried Roubo away on their shoulders in triumph.

The dome was roofed in lead and copper with large vertical strips of glass to illuminate the interior. The structure performed as designed for almost 20 years until it was destroyed in 1802 by wood’s ancient enemy: fire. The dome was later rebuilt in iron, and the work took not five months, but five years to complete, between 1806 and 1811. The building now houses France’s Ministry of Commerce and Industry.

Boileau wrote that the innovative structure made Roubo famous throughout Europe and brought in a lot of business both in Paris and from around the continent. It is also said that the dome was much admired by a later visitor to Paris, the then-American ambassador to France, Thomas Jefferson, who famously had a thing for domes.

— Brian Anderson

Editor’s note: You can order our special edition of “To Make as Perfectly as Possible: Roubo on Marquetry” until the end of January 2013 and guarantee you will receive a copy. Details in our store.

This is pretty interesting.

Thanks

Reblogged this on essencedebois.

The first book is very tempting but I need a new band saw first.

Very interesting and informative, thank you!

The dome at the exchange under which he ogled the domes on a dame is linked to the dome on our change?

Cool.

Very clever.

This reminds me that a few years ago I stumbled on the name of Roubo in George Izenour’s “Theater Design”. Roubo gets a short section discussing his “Treatise on Construction of Theatres and Theatre Machinery” in 1777. He evidently proposed a building “Salle de Spectacle”. Chris, if you are interested I can send you a couple pages of scans, including illustrations from Izenour’s book. Paul

Thanks for posting this. I have been wanting to build a wooden domed conservatory with curved glass for protecting my plants in the winter. I will have to dig up “Inventions Pour Bien Batir à Petites Frais.” Paul, I would be interested in seeing the scans you have from Izenour’s book as well.

I just ordered two videos from Larry williams on moulding planes. When they get here I will order the book

Fascinating! Thanks Brian.

Last summer, I had the opportunity to visit Thomas Jefferson’s Monticello. After seeing the dome on the top of Jefferson’s house, and the dome at the University of Virginia (where he was a co-founder) which he made sure he could see from his veranda, and reading this article, I am very eagerly looking forward to the forthcoming publication of your Roubo book.

Some people really know how to write.